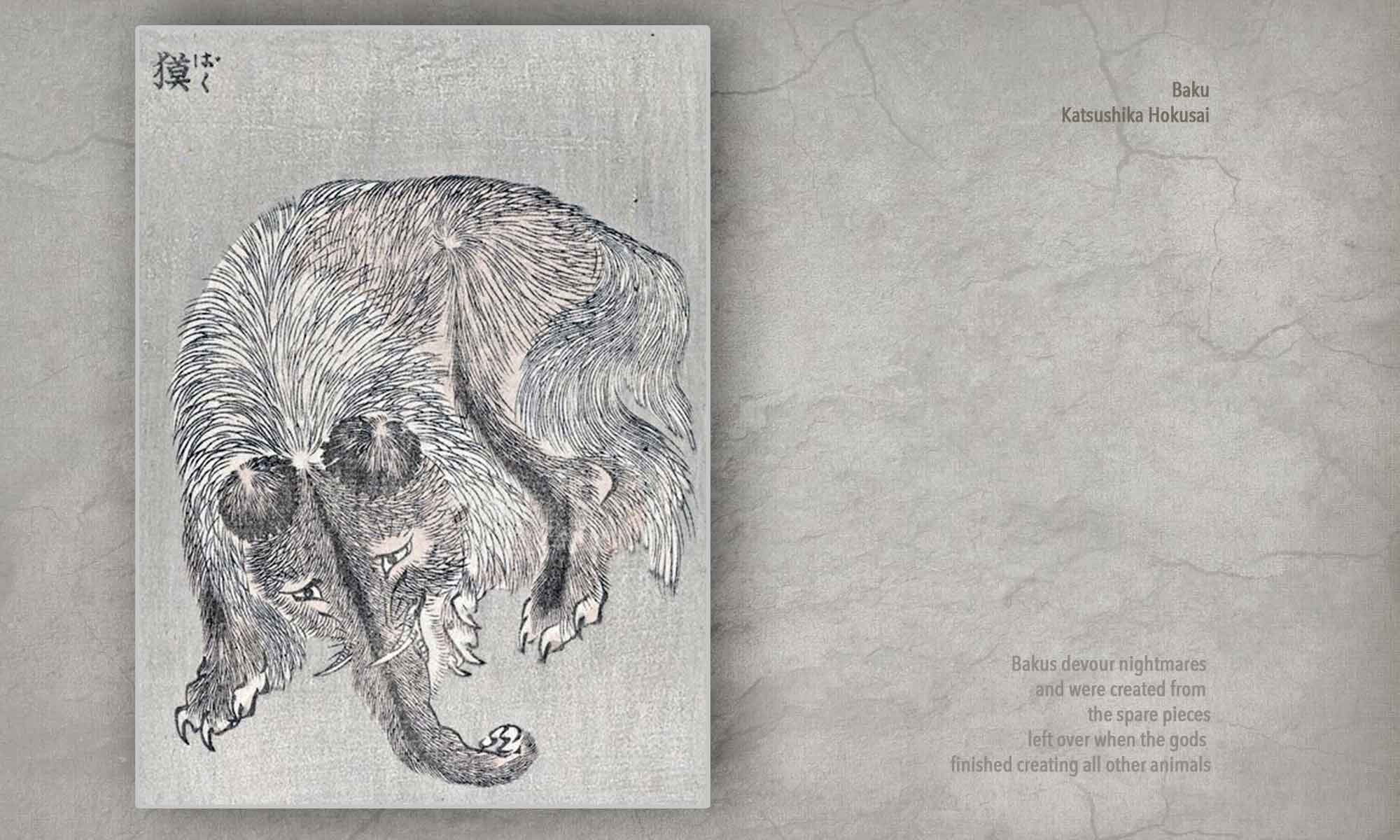

It’s more than a metaphor to say that Halloween is a time when our nightmares go on parade. The scary images, decorations, and costumes that take over the month of October have a direct psychological connection to the actual themes and patterns of people’s nightmares. If we look at current research on nightmares—who has them, what they’re about, what causes them—we can gain new insight into the unconscious creativity of our Halloween festivities.

It’s more than a metaphor to say that Halloween is a time when our nightmares go on parade. The scary images, decorations, and costumes that take over the month of October have a direct psychological connection to the actual themes and patterns of people’s nightmares. If we look at current research on nightmares—who has them, what they’re about, what causes them—we can gain new insight into the unconscious creativity of our Halloween festivities.

Who has nightmares? Numerous studies have reached the same conclusion: children are especially prone to nightmares, and so are women. Let’s start with age. The younger you are, the more likely you experience nightmares. Ernest Hartmann’s 1984 book The Nightmare notes the frequency of nightmares in children between the ages of 3 and 6, and he suggests that bad dreams may begin even earlier than this: “It is quite likely that nightmares can occur as early as dreams can occur; that is, probably late in the first year of life.”

The age factor shows up clearly in the nightmare patterns of adults. In a 2010 survey (available in the Sleep and Dream Database) in which 2,993 American adults answered a series of questions about sleep and dreams, the following are the percentages of people in different age groups who answered “Yes” to the question, “Have you ever had a dream of being chased or attacked?”

Chasing/Attack dreams, by age:

18-24: 71%

25-34: 65%

35-54: 59%

55-69: 48%

70+: 40%

Now for gender. Women tend to have more nightmares than men do, although how much more seems to vary during the life cycle. A meta-analysis by Michael Schredl and Iris Reinhard in 2011 found a striking pattern: similar frequencies of nightmares for males and females in childhood and old age, but a significantly higher frequency of nightmares for females during adolescence and adulthood. There seems to be a “nightmare bump” during women’s lives that elevates their frequency of bad dreams consistently higher than men’s. Is this nature or nurture? Probably both. A similar pattern appears in the 2010 SDDb survey cited above, when analyzed in terms of gender.

Chasing/Attack dreams for men, by age:

18-24: 68%

25-34: 63%

35-54: 56%

55-69: 47%

70+: 37%

Chasing/Attack dreams for women, by age:

18-24: 82%

25-34: 71%

35-54: 65%

55-69: 50%

70+: 46%

No matter how we explain these differences—more on that below—the basic pattern seems clear. Nightmares are especially frequent early in life, and especially for women during adolescence and young adulthood.

What do we have nightmares about? The most common content is fear, of course. And yet, what terrifies one person may have no emotional impact on someone else, so it’s difficult to generalize about the contents of nightmares. Still, it is possible to identify a few typical elements. In the SDDb, I selected four types of dream text (“bad dream,” “nightmare,” “nightmares,” “worst nightmare”), of 25+ words in length, which yielded a set of 423 dreams. I analyzed these 423 dreams using a word-search method with a template of 40 categories of content. I then compared the nightmare results to the results for the SDDb Baselines, a collection of more than 5,000 dreams representing ordinary patterns of dream content.

The dreams in the Baselines average about 100 words per report, while the 423 nightmares have an average length of only 65 words per report. This means the Baselines will tend to have higher frequencies on all categories. That’s actually helpful for our purposes, because it makes it easy to spot the categories that are unusually high in the nightmares (Baselines included in parentheses):

Fire: 4.7% (4.3%)

Air: 6.4% (4.4%)

Falling: 10.9% (8.3%)

Death: 18.4% (8%)

Fantastic beings: 10.4% (2.1%)

Physical aggression: 42.1% (17.6%)

Religion: 7.1% (6.7%)

Weapons: 9.9% (3.9%)

These are the categories of content that seem to be over-represented in nightmares, appearing more often in bad dreams than in ordinary dreams. They are also the themes that characterize pretty much every horror movie ever made, and countless video games, and, of course, many of the costumes and decorations of Halloween.

Why do we have nightmares? Psychologists have offered several theories about this. For Sigmund Freud, a nightmare is a failure of the sleeping mind to contain the instinctual desires aroused in dreaming. Similarly, the neurocognitive theory of Ross Levin and Tore Nielsen explains nightmares as a failure of emotional regulation during sleep. Carl Jung viewed nightmares as reflections of inner conflict, and thus potential revelations of insight and guidance. Antti Revonsuo’s “threat simulation theory” focuses on chasing nightmares and their potentially beneficial role in preparing the individual for similar threats in waking life.

The simple fact that nightmares are so common seems to be evidence against a theory of dreaming as a form of play (such as I propose). How can a frightening experience be playful? Actually, a theory of dreaming as play has a good explanation for the prevalence of nightmares. Research on play in animals and humans has found that play-fighting is one of the most common forms of play among social species like ours. Although it’s not “real” fighting, play-fighting does involve real aggression, threats, and negative emotions, and it seems to have a valuable rehearsal/preparatory function similar to other forms of play. Paradoxically, play-fighting can also promote social bonding by creating a safe arena to work through interpersonal tensions.

This brings us back to the connection between nightmares and Halloween. Seen in this light, the many little rituals of Halloween are ways of playing with our nightmares, welcoming them into waking awareness, sharing them with others, and celebrating their wild creative energies. Once each year, we invite these energies into the community as a way of enlivening and strengthening our collective bonds, at a time when daylight is waning and the nights are growing colder. This is the psychological wisdom of Halloween, infusing us with a playful burst of unconscious vitality just as we’re preparing to survive through the coming darkness.

Note: this post first appeared in Psychology Today on October 21, 2021.

Earlier this week I attended the preseason basketball game between the Portland Trailblazers and the Sacramento Kings. Although the Blazers played with lots of energy, the Kings beat them handily, 107-93. That night (it was a Monday), I had the following dream:

Earlier this week I attended the preseason basketball game between the Portland Trailblazers and the Sacramento Kings. Although the Blazers played with lots of energy, the Kings beat them handily, 107-93. That night (it was a Monday), I had the following dream: Despite the many crises afflicting the world right now, or perhaps because of them, my Muses have been quite active recently. Urgent, even. They have inspired several writing projects I hope to share soon.

Despite the many crises afflicting the world right now, or perhaps because of them, my Muses have been quite active recently. Urgent, even. They have inspired several writing projects I hope to share soon.  Escape from Mercury – a science-fiction novel, co-edited with T.A. Reilly, in production with a private publisher, to be released on 1/1/22 at 13:00 ICT. The novel portrays an alternate history in which NASA launches a manned mission to the planet Mercury on December 3, 1979, using Apollo-era rocketry that was specifically designed for post-Lunar flights. In the present “real” timeline, those plans were abandoned. The novel reimagines the US space program continuing onward and aggressively pushing beyond the Moon, and suddenly discovering dimensions of our interplanetary neighborhood unforeseen by any but the darkest of Catholic demonologists. “The Exorcist in Space” is the tagline.

Escape from Mercury – a science-fiction novel, co-edited with T.A. Reilly, in production with a private publisher, to be released on 1/1/22 at 13:00 ICT. The novel portrays an alternate history in which NASA launches a manned mission to the planet Mercury on December 3, 1979, using Apollo-era rocketry that was specifically designed for post-Lunar flights. In the present “real” timeline, those plans were abandoned. The novel reimagines the US space program continuing onward and aggressively pushing beyond the Moon, and suddenly discovering dimensions of our interplanetary neighborhood unforeseen by any but the darkest of Catholic demonologists. “The Exorcist in Space” is the tagline. 2020 Dreams – a digital project co-authored with Maja Gutman, under contract with Stanford University Press as part of their new Digital Projects Program. We are looking at a large collection of dreams that people experienced during the year 2020, and using a variety of cutting-edge tools of data analysis and visualization to highlight patterns in the dreams and their meaningful connections to major upheavals in collective life–the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental disasters, protests for social justice, and the US Presidential election. We have just reached an agreement with the Associated Press (AP) to use their news data from 2020 as our waking-world comparison set. Our hope is to expand on the findings of Charlotte Beradt and others who have shown how dreams can reflect the impact of collective realities on individual dreams, thus providing a potentially powerful tool of social and cultural analysis.

2020 Dreams – a digital project co-authored with Maja Gutman, under contract with Stanford University Press as part of their new Digital Projects Program. We are looking at a large collection of dreams that people experienced during the year 2020, and using a variety of cutting-edge tools of data analysis and visualization to highlight patterns in the dreams and their meaningful connections to major upheavals in collective life–the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental disasters, protests for social justice, and the US Presidential election. We have just reached an agreement with the Associated Press (AP) to use their news data from 2020 as our waking-world comparison set. Our hope is to expand on the findings of Charlotte Beradt and others who have shown how dreams can reflect the impact of collective realities on individual dreams, thus providing a potentially powerful tool of social and cultural analysis. The Scribes of Sleep: Insights from People Who Keep Dream Journals – a non-fiction book in psychology and religious studies. Currently being written, under contract with Oxford University Press, likely publication in early 2023. This book brings together many sources of research about people who record their dreams over time, and what they learn from the practice. Seven historical figures are the primary case studies in the book: Aelius Aristides, Myoe Shonin, Lucrecia de Leon, Emanuel Swedenborg, Benjamin Bannecker, Anna Bonus Kingsford, and Wolfgang Pauli. A close look at their lives, their dreams, and their creative works (religiously, artistically, scientifically) suggests that keeping a dream journal seems to appeal to people with a certain kind of spiritual attitude towards the world. The stronger argument is that keeping a dream journal actively cultivates such an attitude….

The Scribes of Sleep: Insights from People Who Keep Dream Journals – a non-fiction book in psychology and religious studies. Currently being written, under contract with Oxford University Press, likely publication in early 2023. This book brings together many sources of research about people who record their dreams over time, and what they learn from the practice. Seven historical figures are the primary case studies in the book: Aelius Aristides, Myoe Shonin, Lucrecia de Leon, Emanuel Swedenborg, Benjamin Bannecker, Anna Bonus Kingsford, and Wolfgang Pauli. A close look at their lives, their dreams, and their creative works (religiously, artistically, scientifically) suggests that keeping a dream journal seems to appeal to people with a certain kind of spiritual attitude towards the world. The stronger argument is that keeping a dream journal actively cultivates such an attitude…. Here Comes This Dreamer: Practices for Cultivating the Spiritual Potentials of Dreaming – a non-fiction book addressed to general readers interested in deeper explorations of their dreaming. Currently being written, under contract with Broadleaf Books, likely publication in the latter part of 2023. The challenge here, both daunting and exciting, is explaining the best findings from current dream research in terms that “curious seekers” will find meaningful and personally relevant. The book will have three main sections: 1) Practices of a Dreamer, 2) Embodied Life, and 3) Higher Aspirations. The title of the book signals a key concern I want to highlight: to be a big dreamer, like Joseph in the Bible (Gen. 37:19), can be amazing and wonderful, but it can also be perceived by others as threatening and dangerous. Sad to say, the world does not always appreciate the visionary insights of people who naturally have vivid/frequent/transpersonal dreams. I want to share what I hope are helpful and reassuring ideas about how to stay true to your innate dreaming powers while living in a complex social world where many people are actively hostile to the non-rational parts of the mind.

Here Comes This Dreamer: Practices for Cultivating the Spiritual Potentials of Dreaming – a non-fiction book addressed to general readers interested in deeper explorations of their dreaming. Currently being written, under contract with Broadleaf Books, likely publication in the latter part of 2023. The challenge here, both daunting and exciting, is explaining the best findings from current dream research in terms that “curious seekers” will find meaningful and personally relevant. The book will have three main sections: 1) Practices of a Dreamer, 2) Embodied Life, and 3) Higher Aspirations. The title of the book signals a key concern I want to highlight: to be a big dreamer, like Joseph in the Bible (Gen. 37:19), can be amazing and wonderful, but it can also be perceived by others as threatening and dangerous. Sad to say, the world does not always appreciate the visionary insights of people who naturally have vivid/frequent/transpersonal dreams. I want to share what I hope are helpful and reassuring ideas about how to stay true to your innate dreaming powers while living in a complex social world where many people are actively hostile to the non-rational parts of the mind.  People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.

People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.

Dreams with explicitly sexual and/or violent interactions tend to get the most attention, but dreams actually tend to have surprisingly high proportions of friendly content, too. According to an analysis of the nearly 35,000 dream reports collected in the Sleep and Dream Database, 47% of the women’s dreams have at least one reference to a friendly social interaction (the most used words: friend, friends, boyfriend, help, party, love), as do 36% of men’s dreams (most used words: friend, friends, girlfriend, help, love, party. For both genders, those figures are greater than the combined percentages for sexual interactions (4% for women, 6% for men) and physically aggressive interactions (15% for women, 22% for men). If we add in non-physical aggressions (for example, saying or thinking mean things about a person), the relative proportions change, but the key fact remains: Friendly social interactions are a prominent feature of the content of most people’s dreams. If dreams offer a “royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious mind,” as Sigmund Freud famously claimed in The Interpretation of Dreams (2nd ed.), giving evidence of our deepest sexual and aggressive instincts, then dreams also provide evidence of our friendly, prosocial instincts.

Dreams with explicitly sexual and/or violent interactions tend to get the most attention, but dreams actually tend to have surprisingly high proportions of friendly content, too. According to an analysis of the nearly 35,000 dream reports collected in the Sleep and Dream Database, 47% of the women’s dreams have at least one reference to a friendly social interaction (the most used words: friend, friends, boyfriend, help, party, love), as do 36% of men’s dreams (most used words: friend, friends, girlfriend, help, love, party. For both genders, those figures are greater than the combined percentages for sexual interactions (4% for women, 6% for men) and physically aggressive interactions (15% for women, 22% for men). If we add in non-physical aggressions (for example, saying or thinking mean things about a person), the relative proportions change, but the key fact remains: Friendly social interactions are a prominent feature of the content of most people’s dreams. If dreams offer a “royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious mind,” as Sigmund Freud famously claimed in The Interpretation of Dreams (2nd ed.), giving evidence of our deepest sexual and aggressive instincts, then dreams also provide evidence of our friendly, prosocial instincts. New technologies are making it possible to use brain data to create video reconstructions of people’s dreams while they sleep. Is this thrilling, terrifying, or both?

New technologies are making it possible to use brain data to create video reconstructions of people’s dreams while they sleep. Is this thrilling, terrifying, or both?