People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.

People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.

Consider as an example “visitation dreams,” dreams in which a loved one who has died appears as if alive again. These dreams are often extremely vivid and realistic. After awakening from such an experience, it’s almost impossible not to wonder, did I just have a real encounter with the soul or ghost of that person? And then to wonder, do I have a disembodied soul of my own? Is that what will happen when I die?

According to cross-cultural surveys of typical dreams like this, visitation dreams appear quite frequently across a wide spectrum of the population (the statistics cited below come from my Big Dreams book in 2016). For instance, in a 1958 study (Griffith et al.) of American and Japanese college students, 40% of the American males and 53% of the American females reported having had at least one visitation dream. In a 1972 study (Giroa et al.) of Israeli Arabs and Kibbutz residents, the figures were 39% for the Kibbutz males, 52% for the Kibbutz females, 70% for the Arab females, and 73% for the Arab males. In a 2001 study (Nielsen et al.) of Canadian college students, the figures were 38% for the Canadian males and 39% for the Canadian females. A 2004 study (Schredl et al.) of German college students yielded the figures of 38% for the German males and 46% for the German females.

These findings show that the experience of visitation dreams is remarkably common and widely distributed. This suggests a large number of people in every culture and community have had at least one intense personal experience that naturally invites spiritual reflection on life, death, and the existence of the soul.

Another example are “flying dreams,” which often bring incredibly strong feelings of elation, freedom, and transcendence. Like visitations, flying dreams also have a dramatic intensity and hyper-realism that makes them highly memorable after awakening, and they just as naturally prompt the conscious mind to imagine radical new possibilities and powers that overcome the limits of ordinary reality.

The cross-cultural frequency of having had at least one flying dream is similar to that of visitation dreams. For the American males it was 32%, and for the American females, 35%. For the Japanese males, 46%, and Japanese females, 46%. For the Kibbutz males, 61%, and Kibbutz females, 40%. For the Arab males, 44%, and Arab females, 43%. For the Canadian males, 58%, and Canadian females, 44%. And for the German males, 66%, and German females, 63%.

The high frequency of flying dreams might not seem like big news. But the point here is to emphasize the implications of this fact for the presence of an innately spiritual impulse and potentiality in our dreaming. These cross-cultural findings suggest that large numbers of people in societies all over the world are innately stimulated in their dreams to recognize their own potentials for transcendence, joy, and powers beyond what our waking minds believe is possible.

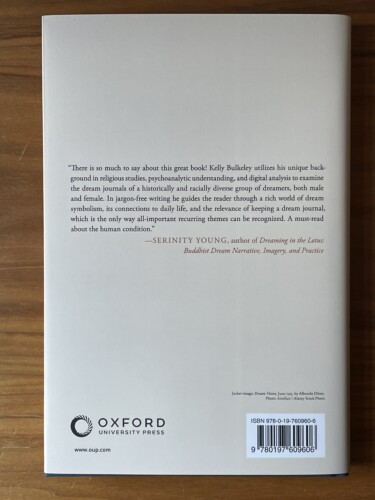

Horrible nightmares might not seem to have any spiritual significance, yet the darkest of dreams can sometimes have a tremendous impact on people. Vivid nightmares certainly have as much emotional intensity and unforgettable imagery as visitation and flying dreams, and they also naturally stimulate the individual’s waking mind to ponder existential and moral questions with deep religious relevance—questions about evil, suffering, justice, violence, and death.

The cross-cultural research shows that nightmares of being chased or attacked are one of the most commonly experienced of all the “typical” dreams. Here are the figures from the studies cited above: American males, 77%, American females, 78%; Japanese males, 90%, Japanese females, 92%; Kibbutz males, 69%, Kibbutz females, 70%; Arab males, 66%, Arab females, 51%; Canadian males, 78%, Canadian females 83%; German males, 87%, German females, 89%.

Nightmares may cause distress and discomfort, but they also quite effectively force the waking mind to pay attention to real dangers, both out in the world and deep within oneself, that require greater awareness and attention. Such dreams can provide moral orientation and guidance in difficult, frightening situations. In some cases, nightmares offer experiences of radical empathy, providing insight into the feelings and sufferings of others and thus opening the individual’s mind to a wider sphere of moral care and responsibility—precisely the goal of many religious traditions.

If you track your dreams over time, or if you have therapy clients who tell you about their dreams, religiously-charged issues will almost certainly come up, sooner or later. Visitation dreams, flying dreams, nightmares, and many other types of dreams offer an open invitation to spiritual inquiry and existential self-reflection. Dreams are metaphysically insistent, but not dogmatic. They illuminate, reveal, and stimulate, but they leave the answers and practical applications to waking consciousness. And best of all in this ultra-commodified age, they are free and available to everyone! Dreams provide a neurologically hard-wired, universally accessible, yet exquisitely personalized portal into realms of awareness and insight that humans have traditionally regarded as a path towards sacred wisdom. Not everyone recognizes or cares about this aspect of their dreams. But the path is always there, opening and beckoning to us every night when we sleep.

Note: this post first appeared in Psychology Today 9/21/21.

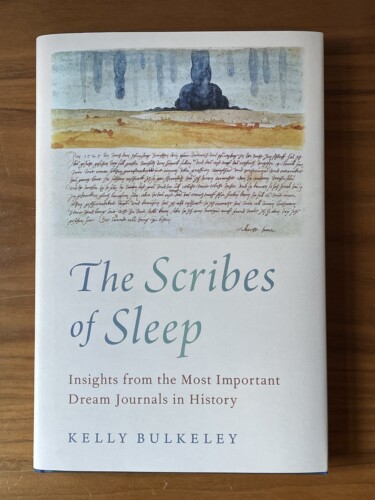

My latest book, The Scribes of Sleep, has just been published by Oxford University Press. It’s a work dedicated to people who keep dream journals, as a new resource for learning more about the fascinating and largely unknown history of dream journal practices. The book is also intended as an argument in favor of dream journals as a valuable source of empirical data for scientific research into the nature and functions of dreaming.

My latest book, The Scribes of Sleep, has just been published by Oxford University Press. It’s a work dedicated to people who keep dream journals, as a new resource for learning more about the fascinating and largely unknown history of dream journal practices. The book is also intended as an argument in favor of dream journals as a valuable source of empirical data for scientific research into the nature and functions of dreaming.

Most people who keep a dream journal are initially motivated by simple curiosity and the hope they will gain insights into their waking lives. But as they continue with the journaling and track the emerging patterns of their dreams over time, they often find the process becomes something more than that, something that develops a life of its own and opens into a new relationship with the unconscious realms of their minds.

Most people who keep a dream journal are initially motivated by simple curiosity and the hope they will gain insights into their waking lives. But as they continue with the journaling and track the emerging patterns of their dreams over time, they often find the process becomes something more than that, something that develops a life of its own and opens into a new relationship with the unconscious realms of their minds. A Dream Library is a playground for studying and dreaming: for studying while dreaming, and dreaming while studying. It’s a spatial technology for stimulating your oneiric imagination. It’s not a shrine to dreaming, but it’s not not a shrine to dreaming, either. It’s your personally crafted portal into the intuitive depths of your own mind.

A Dream Library is a playground for studying and dreaming: for studying while dreaming, and dreaming while studying. It’s a spatial technology for stimulating your oneiric imagination. It’s not a shrine to dreaming, but it’s not not a shrine to dreaming, either. It’s your personally crafted portal into the intuitive depths of your own mind. People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.

People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.

When someone is about to share a dream with me, either in a group setting or one-on-one, I always ask for two things. First, please tell the dream in the present tense, not the past tense, so the dream feels immediate, like it’s happening right now. And second, please share the dream twice. After you have told it once, tell the whole thing again.

When someone is about to share a dream with me, either in a group setting or one-on-one, I always ask for two things. First, please tell the dream in the present tense, not the past tense, so the dream feels immediate, like it’s happening right now. And second, please share the dream twice. After you have told it once, tell the whole thing again. Dreams during the holidays bring happy memories, and recurrent anxieties.

Dreams during the holidays bring happy memories, and recurrent anxieties.