An academic dissertation is written in compliance with a host of official requirements designed to focus the project and give it the best chance of successful completion. Those requirements definitely influenced how my dissertation and first book, The Wilderness of Dreams (1994), came to be what it is. As I sat down to write my second book, I remember a moment of almost dizzy uncertainty about taking the first steps forward. I knew even before finishing WD that I wanted to write a book about the religious and spiritual aspects of dreaming through history. The first chapter of my dissertation offered a survey of that material, but I had accumulated a larger store of references, much more than could be presented in a single chapter. A book-length study seemed worthwhile, but what exactly would it look like?

An academic dissertation is written in compliance with a host of official requirements designed to focus the project and give it the best chance of successful completion. Those requirements definitely influenced how my dissertation and first book, The Wilderness of Dreams (1994), came to be what it is. As I sat down to write my second book, I remember a moment of almost dizzy uncertainty about taking the first steps forward. I knew even before finishing WD that I wanted to write a book about the religious and spiritual aspects of dreaming through history. The first chapter of my dissertation offered a survey of that material, but I had accumulated a larger store of references, much more than could be presented in a single chapter. A book-length study seemed worthwhile, but what exactly would it look like?

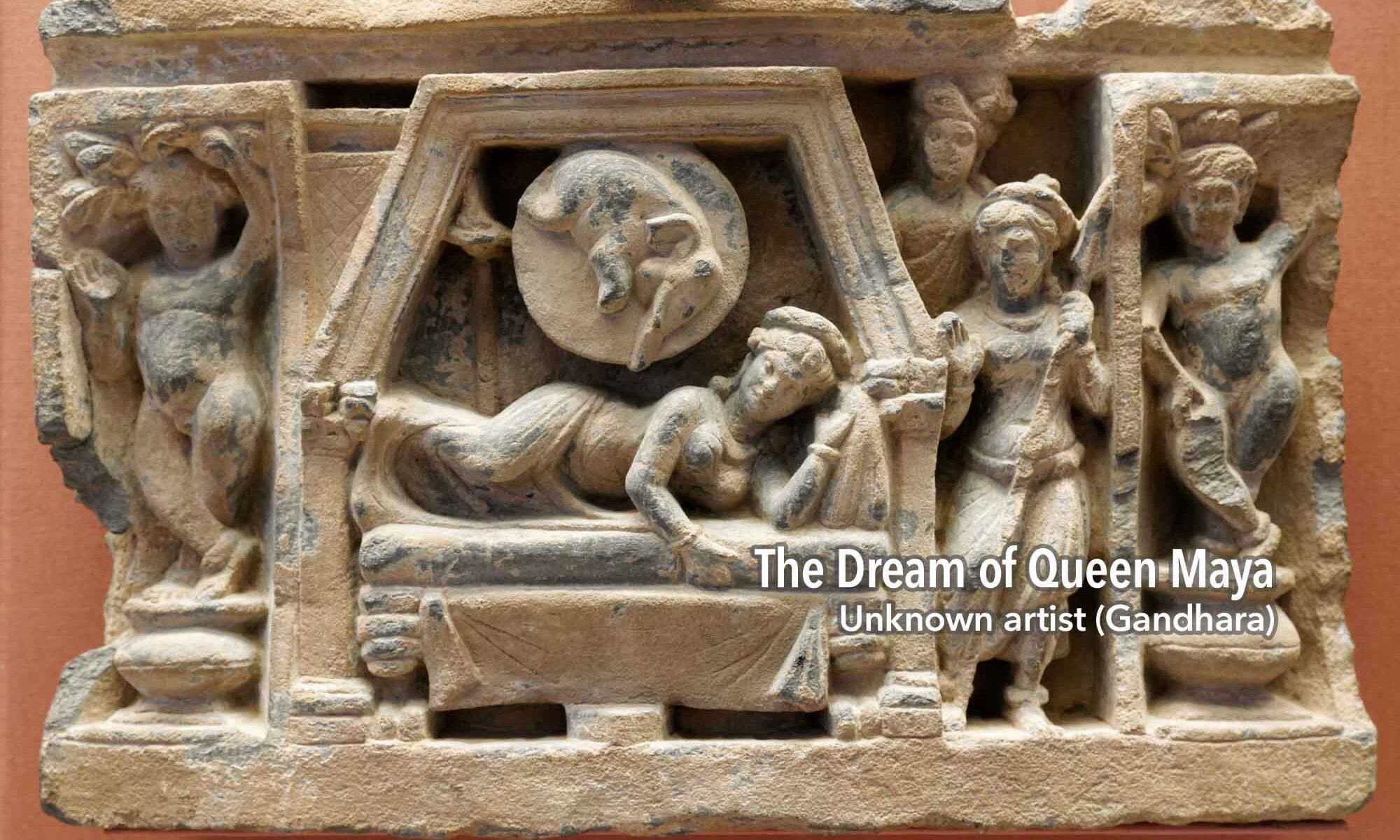

What emerged was a first foray into the typologies of dreaming. Shaped and inspired by the ideas of Mircea Eliade, Rudolf Otto, Wendy Doniger, and Harry Hunt, I cast a wide net across historical and cross-cultural sources for references to dreams and dreaming. Then, taking into account the provisional nature of all such typologies, I grouped these references into what seemed to me to be natural categories, natural in the sense of sharing core features (of imagery, emotion, and carry-over effects) across differences of time and place. In this sense, Spiritual Dreaming was a history of religions project, using dream research as the means of comparison. These are the categories I identified and discussed, one per chapter:

- The Dead

- Snakes

- Gods

- Nightmares

- Sexuality

- Flying

- Lucidity

- Creativity

- Healing

- Prophecy

- Rituals

- Initiation

- Conversion

For each dream category, I gathered examples from multiple cultures, religious traditions, and periods of history and discussed them in relation to current dream research, from Freud and Jung to current brain-mind science. These categories and my initial ideas about their psycho-spiritual coherence remain vital influences on my work. The four appendices are especially important in formulating several early theses about dreaming and philosophy that I hope to expand upon at some point in the future.

This was also an important text for me in trying to create a space to talk about dream-related beliefs, practices, and experiences that can be described as religious and/or spiritual. I think it helps clarify the true nature of dreaming to include religious and spiritual perspectives, and after explaining what I do and don’t mean by these terms at the beginning of the book, I put the analytic emphasis on the dreams themselves to see what we can learn from them.

My friend and mentor Jeremy Taylor had published Dream Work (1983) with Paulist Press and spoke highly of their editor, Lawrence Boadt. That’s how I came to make an arrangement with Paulist to publish Spiritual Dreaming, with back-cover endorsements from Patricia Garfield and Lewis Rambo. Patricia was a co-founder of the IASD and author of several well-regarded books on dreams, and Lewis was a professor of religion and psychology at San Francisco Theological Seminary and my faculty sponsor at the Graduate Theological Union, where I had become a Visiting Scholar after leaving Chicago.

My friend and mentor Jeremy Taylor had published Dream Work (1983) with Paulist Press and spoke highly of their editor, Lawrence Boadt. That’s how I came to make an arrangement with Paulist to publish Spiritual Dreaming, with back-cover endorsements from Patricia Garfield and Lewis Rambo. Patricia was a co-founder of the IASD and author of several well-regarded books on dreams, and Lewis was a professor of religion and psychology at San Francisco Theological Seminary and my faculty sponsor at the Graduate Theological Union, where I had become a Visiting Scholar after leaving Chicago.

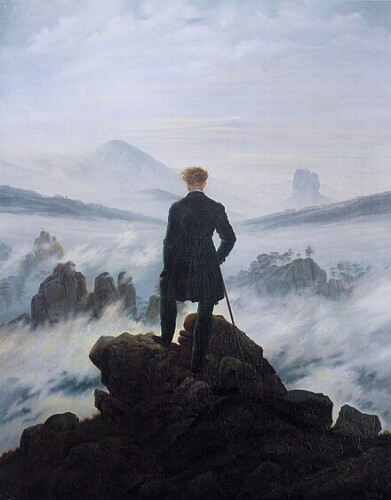

The front cover is a painting from Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog (1818), a classic of early Romantic aesthetics, although I didn’t know that at the time—I just liked the way this image balanced the cover of WD, which was set deep inside a Redwood-lined creek; here with SD, we’re reaching the top of the ridge and discovering a big open view to enjoy.

The front cover is a painting from Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog (1818), a classic of early Romantic aesthetics, although I didn’t know that at the time—I just liked the way this image balanced the cover of WD, which was set deep inside a Redwood-lined creek; here with SD, we’re reaching the top of the ridge and discovering a big open view to enjoy.

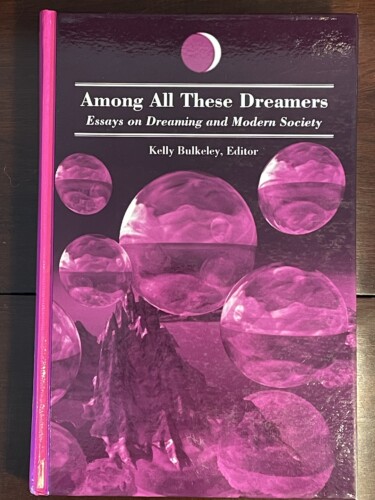

The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.

Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.