I’d like to illustrate some basic principles of dream interpretation by telling a story. It’s a very old story, one you may have heard before, but I’d like to tell it again because even though it’s “just a story” it highlights the real perils that come when these dream interpretation principles are overlooked.

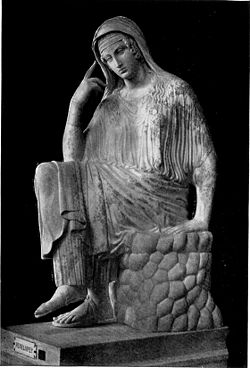

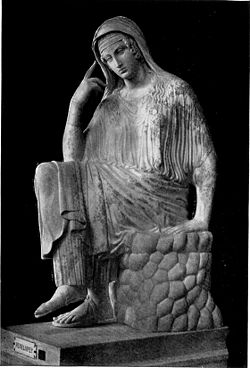

The story has to do with the meeting of Odysseus and Penelope in Book 19 of The Odyssey. In many respects this encounter is the point of greatest dramatic intensity in the entire poem, and at the heart of the scene is a dream-Penelope’s dream of the twenty geese that are suddenly slaughtered by a mountain eagle. Odysseus, after leading the Achaean army to victory against the Trojans and after enduring a seemingly endless series of trials and adventures, has returned at last to his island home of Ithaca, where he has found a mob of rude noblemen besieging his palace. The crafty warrior has disguised himself as an old beggar in order to gain entrance into the palace without being recognized, and he is plotting violent revenge against the men who would steal his throne. Penelope, who for many years has desperately clung to the hope that Odysseus would someday return to her, has invited this strange wanderer into her private chambers to ask if he can tell her any news of her husband. The beggar fervently promises the Queen that Odysseus is very close and will return very, very soon. Penelope replies to the beggar’s story by saying she wishes his words would come true, but she doubts they will. She then asks her old servant woman, Eurycleia, to bathe the stranger and arrange a comfortable place for him to sleep. The Queen steps away while the old nurse washes the beggar’s feet. Then, before parting for the night, Penelope returns to the beggar and says (all quotes are from the translation of Robert Fagles, 1996, Viking Press),

“My friend, I have only one more question for you….

[P]lease, read this dream for me, won’t you? Listen closely….

I kept twenty geese in the house, from the water trough

They come and peck their wheat-I love to watch them all.

But down from a mountain swooped this great hook-beaked eagle,

Yes, and he snapped their necks and killed them one and all

And they lay in heaps throughout the hall while he,

Back to the clear blue sky he soared at once.

But I wept and wailed-only a dream, of course-

And our well-groomed ladies came and clustered round me,

Sobbing, stricken: the eagle killed my geese. But down

He swooped again and settling onto a jutting rafter

Called out in a human voice that dried my tears,

‘Courage, daughter of famous King Icarius!

This is no dream but a happy waking vision,

Real as day, that will come true for you.

The geese were your suitors-I was once the eagle

But now I am your husband, back again at last,

About to launch a terrible fate against them all!’

So he vowed, and the soothing sleep released me.”

(The Odyssey 19.575, 603-621)

The disguised Odysseus immediately replies,

“Dear woman,….twist it however you like,

Your dream can mean only one thing. Odysseus

Told you himself-he’ll make it come to pass,

Destruction is clear for each and every suitor;

Not a soul escapes his death and doom.”

(The Odyssey 19.624-629)

Penelope’s response to the beggar is this:

“Ah my friend, seasoned Penelope dissented,

Dreams are hard to unravel, wayward, drifting things-

Not all we glimpse in them will come to pass….

Two gates there are for our evanescent dreams,

One is made of ivory, the other made of horn.

Those that pass through the ivory cleanly carved

Are will-o’-the-wisps, their message bears no fruit.

The dreams that pass through the gates of polished horn

Are fraught with truth, for the dreamer who can see them.

But I can’t believe my strange dream has come that way,

Much as my son and I would love to have it so.”

(The Odyssey 19.630-640)

So, what has just happened here? What is going on between Odysseus and Penelope, and what is the significance of her dream and their exchange about its meaning? The traditional interpretation of this scene, shared with near unanimity by scholars from antiquity to the present, is this. Odysseus has heroically controlled his desire to rejoin Penelope and hidden his identity from her for two reasons: one, to test his wife’s fidelity during his long absence (remember Agamemnon and Clytemnestra), and two, to pick up information about how to destroy the hated suitors. Penelope’s dream of the 20 geese is a straightforward prophecy, whose true meaning the disguised Odysseus instantly recognizes. But Penelope, who has shown a stubborn skepticism throughout the story, refuses to accept the dream’s obvious meaning. Indeed, perhaps she unconsciously enjoys the attention of the suitors and does not really want Odysseus to come back.

My dissatisfaction with this widely held interpretation centers on its strange depreciation of Penelope’s intelligence. This is a woman whom several characters have praised for her unrivalled perceptiveness, cunning, and guile; this is the woman who devised the famous ruse of the funeral shroud, by which she successfully deceived the suitors for three years. All of the evidence in the poem makes it clear that Penelope is not a fool: she is extremely perceptive and capable of remarkably subtle deceptions. So why, when we come to Book 19 and her meeting with the “beggar,” should we now forget all that and regard Penelope as a pathetically unwitting dupe in the vengeful scheming of Odysseus?

Here is the moment when careful reflection on Penelope’s dream can open up new horizons of meaning. The Iliad and The Odyssey together contain, up to the point of Penelope’s dream of the 20 geese, four major dream episodes: Agamemnon’s “Evil Dream” from Zeus (2.1-83), Achilles’ mournful dream of the spirit of dead Patroklos (23.54-107), Penelope’s reassuring dream from Athena (4.884-946), and Nausicaa’s arousing marriage dream from Athena (6.15-79). Viewed in this context, Penelope’s dream is unusual in at least two ways:

- One, this is the only dream that occurs “offstage,” out of direct view of the audience. We do not “see” the dream while it is happening; we only hear the dreamer describe it, after the fact.

- Two, this is the only “symbolic” dream, with its meaning encoded in stylized imagery. The dream thus poses a riddle, which must be accurately interpreted for the true meaning to emerge.

I believe these two details suggest a very different reading of the encounter between Penelope and the disguised Odysseus. Could it be that this is not a “real” dream at all, that in fact Penelope has made it up? Could it be that Penelope is deliberately using the riddle of her dream as a test to find out the intentions of this man, whom she consciously suspects is Odysseus? Could it be that while he thinks he’s deceiving her, she’s really the one deceiving him?

This would not be the first time in Homer’s poems that dreams have been used to deceive and manipulate others-in fact, it would be the fourth time: Zeus sending the “Evil Dream” to Agamemnon, Athena sending the “marriage dream” to Nausicaa, and Odysseus (at the end of The Odyssey, Book 14) making up a story about the “real” Odysseus making up a dream in order to steal another warrior’s cloak on a cold, windy night (14.519-589).

Why would Penelope make up such a dream? The answer emerges if we think carefully about what is happening at that crucial moment when the old nurse Eurycleia is washing the beggar’s feet. Penelope has removed herself and is standing alone, after a long and intimate conversation with a man who has detailed knowledge about Odysseus, who looks and sounds very much like Odysseus, who insists with passionate certainty that Odysseus will return to the palace the very next day. The question could hardly not arise for this most intelligent and perceptive of women: is this stranger Odysseus himself? If he is, then why isn’t he revealing himself? Penelope has just poured her heart out to him, saying how terribly she has suffered over the years-why won’t he drop his disguise and reunite with her this very moment?

When Eurycleia finishes washing the beggar’s feet, Penelope returns to him and says she has one last question-what is the meaning of her dream of the geese and the mountain eagle? The disguised Odysseus eagerly agrees with the words of the mountain eagle in the dream: the dream means “destruction is clear for each and every suitor.”

Penelope, however, disagrees. Her “two gates” speech that follows is a subtle but unmistakable way of saying “I don’t think so” to the beggar’s interpretation. She cannot agree with him for a simple reason: the mountain eagle and the beggar have both misinterpreted the dream. There are 20 geese in her dream, but more, many more than that number of suitors in the palace. As we learn in Book 16.270-288, where Telemachus tells Odysseus who all the suitors are and where they come from, there are a total of 108 men besieging the palace. Penelope’s refusal to accept the interpretation of the mountain eagle and the beggar is not due to stubborn skepticism, pathetic ignorance, or unconscious desire-she rejects the interpretation because it is wrong. The true meaning of the symbol of the 20 geese is surprisingly easy to find if we do not automatically assume that the mountain eagle and the beggar are right (that is, if we do not automatically privilege the hermeneutic perspective of Odysseus). The 20 geese symbolize the 20 years that Odysseus has been away fighting the war at Troy and journeying through the world. The exact length of Odysseus’ absence, 20 years, is mentioned five separate times in the poem, and most significantly the beggar himself comments to Penelope a few lines earlier in Book 19 that Odysseus has been gone for 20 years.

Thus, the first part of Penelope’s dream symbolically, and very accurately, describes her emotional experience of what has happened between them: Odysseus, by going off to fight in someone else’s war, has destroyed the last 20 years for her. What should have been the prime years of their marriage, the wonderful years of raising a family and creating a home, the years that Penelope would have “loved to watch” and care for, have been slaughtered by Odysseus. The second part of the dream expresses Penelope’s fearful perception of Odysseus right now, still standing apart from her in the disguise of a beggar. He doesn’t recognize her, and what the last 20 years have been like for her; all he can see are the suitors and a galling challenge to his honor. By posing this dream riddle to the beggar, Penelope is in effect asking if her suspicion is true: is the “real” Odysseus as blind to her feelings and as obsessed with killing the suitors as is the “dream” Odysseus? When the beggar agrees with the mountain eagle’s words in the dream, Penelope knows the unfortunate answer.

The mysterious poetry of Penelope’s two gates speech becomes all the more powerful when it is understood as a response to Odysseus’ failure of the dream interpretation test. To his reprimanding words, “twist it however you like, your dream can only mean one thing,” Penelope replies that dreams are always difficult to understand, and they do not always come true. The danger is that we will allow our desire to cloud our perception-taking as divine prophecy what is merely human fantasy. But some dreams, she goes on to say, do have the potential to come true-though only “for the dreamer who can see them.” That is precisely what Odysseus has failed to do. He has failed to see past his own desire for revenge.

I am reluctant to finish with this story, because there is so much more to be told (and so much more to be questioned, if you happen to disagree with my admittedly unorthodox reading of this scene). But I will close by reflecting on the interpretive principles guiding this approach to Penelope’s dream of the 20 geese. First, I chose to privilege the perspective of the dreamer, listening to her words, looking carefully at her experience, asking critical questions of her motivations, and ultimately grounding the dream’s meaning in the conditions of her waking life. Second, I focused special attention on the details of the dream, particularly on the exact number of geese, 20. Third, I located the dream in the context of broader cultural patterns, focusing in particular on how Penelope’s dream deviates from the narrative structuring of other Homeric dreams. And fourth, I tried to look beyond the seemingly obvious and self-evident to discover the new, the surprising, the unexpected.

Of the four classical elements—fire, air, water, and earth—water tends to be the one that appears most frequently in people’s dreams.Some of this is due to the importance of water in our daily existence, and in the existence of all of Earth’s creatures. Some of it is also due to the psychological potency of water as a symbol of life, birth, emotions, fluidity, the feminine, the unconscious, and several other meanings that vary by culture and historical era. If you reflect on your own dreams and follow their development over time, you will likely notice the appearance of water in multiple forms. Here are some questions to keep in mind as you reflect on the presence of water in one of your dreams.

Of the four classical elements—fire, air, water, and earth—water tends to be the one that appears most frequently in people’s dreams.Some of this is due to the importance of water in our daily existence, and in the existence of all of Earth’s creatures. Some of it is also due to the psychological potency of water as a symbol of life, birth, emotions, fluidity, the feminine, the unconscious, and several other meanings that vary by culture and historical era. If you reflect on your own dreams and follow their development over time, you will likely notice the appearance of water in multiple forms. Here are some questions to keep in mind as you reflect on the presence of water in one of your dreams.