In February of 1815 a baby girl was born two months prematurely to Mary Godwin, seventeen years old at the time, and the poet Percy B. Shelley. Twelve days later Mary went to the child during the night and found she had died in her sleep. On March 19, 1815 Mary recorded the following dream in her journal:

In February of 1815 a baby girl was born two months prematurely to Mary Godwin, seventeen years old at the time, and the poet Percy B. Shelley. Twelve days later Mary went to the child during the night and found she had died in her sleep. On March 19, 1815 Mary recorded the following dream in her journal:

“Dreamt that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lived. Awake and find no baby. I think about the little thing all day. Not in good spirits.”

It would be easy to interpret this dream as a guilt-driven fantasy, a classic Freudian wish fulfillment. We don’t know for sure, but we can fairly assume that Mary felt deeply saddened and somehow personally responsible for her child’s death. The dream, in this view, satisfies her desire to defy death and magically restore her child’s life rather than tragically losing it.

The limits of that interpretation become apparent when the dream’s waking life impact is taken into account. The dream did not diminish or obscure Mary’s awareness of what had happened. On the contrary, the dream made Mary more aware of the reality of her child’s death and more conscious of her agonizing feelings of loss. Far from a soothing delusion, this dream’s message to Mary seems almost cruel in its stark honesty: “Awake and find no baby.”

A better interpretation, I believe, starts with the dream’s emotional impact on her waking life. Mary’s dream marks a significant moment in her mourning process, her psyche’s way of making sense of a devastating loss and trying to reorient towards future growth. Mary’s dream does not hide or disguise her child’s death. When she wakes up, her first thought brings a fresh sense of loss and sadness. But the dream also introduces a spark of vitality into Mary’s awareness. Warmth, fire, and vigorous activity do indeed stimulate the creation of new life. Mary’s dream is not delusional about that piece of primal wisdom. Mary may not have been able to bring her baby back to life, but she still had the drive, desire, and knowledge to create again.

Out of her mourning Mary did find new creative energies. In January of 1816 she bore a healthy son, William. That summer, she and Percy Shelley visited the poet Lord Byron at his villa beside Lake Geneva in Switzerland, where Mary conceived the idea for her first novel: “Frankenstein, or, the Modern Prometheus.”

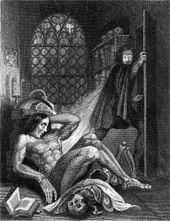

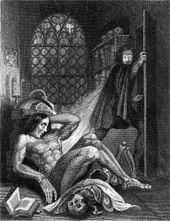

“Frankenstein” surely reflects the same wishful fantasy as Mary’s dream of the previous year, i.e., bringing the dead back to life. But the differences are significant: In her dream, a mother tries to reanimate her daughter, whereas in “Frankenstein,” a male scientist tries to animate a creature stitched together from many different bodies. The dream portrays a natural human desire for a personal relationship, while the story presents an unnatural and inhuman desire for impersonal control over another’s life. In “Frankenstein” Mary adds to her dream a dimension of horror and madness, along with a prescient critique of the self-destructive hubris and masculine grandiosity of modern science. I don’t know much about her relationship with Percy Shelley, Byron, and other male poets, but I would guess that “Frankenstein” also reflects Mary’s feelings about gender, sexuality, and literary creativity.

“Frankenstein” surely reflects the same wishful fantasy as Mary’s dream of the previous year, i.e., bringing the dead back to life. But the differences are significant: In her dream, a mother tries to reanimate her daughter, whereas in “Frankenstein,” a male scientist tries to animate a creature stitched together from many different bodies. The dream portrays a natural human desire for a personal relationship, while the story presents an unnatural and inhuman desire for impersonal control over another’s life. In “Frankenstein” Mary adds to her dream a dimension of horror and madness, along with a prescient critique of the self-destructive hubris and masculine grandiosity of modern science. I don’t know much about her relationship with Percy Shelley, Byron, and other male poets, but I would guess that “Frankenstein” also reflects Mary’s feelings about gender, sexuality, and literary creativity.

Mary’s dream of her baby daughter did not simply inspire the “bring the dead back to life” plot line of “Frankenstein.” The dream prompted a transformative deepening of her awareness about the creative tension between life and death, an awareness that enabled her to infuse “Frankenstein” with critical insight, emotional poignancy, and existential wonder.

Below is the section on animal dreams from my video talk for the IASD Australian Regional Conference held last week in Sydney. I would be very interested in hearing from people whose dreams include types of animals NOT mentioned in my findings, to help us develop an even broader sense of oneiro-zoology (yes that’s a made up word!).

Below is the section on animal dreams from my video talk for the IASD Australian Regional Conference held last week in Sydney. I would be very interested in hearing from people whose dreams include types of animals NOT mentioned in my findings, to help us develop an even broader sense of oneiro-zoology (yes that’s a made up word!).

To summarize the results of the word search analysis so far:

To summarize the results of the word search analysis so far: