The Blazers beat the Memphis Grizzlies, 116-96, last Wednesday night, to even their season’s record at 2 wins and 2 losses. They played excellent defense and held Ja Morant, the Grizzlies’ young star guard, to 17 points, half of what he had been averaging the first few games of the season. The Blazers had a strong second half, with more amazing dance-and-shoot moves from C.J. McCollum, who plays with astonishing grace and fluidity. He excels at step-back jumpers, mid-lane floaters, sneaky inside drives, and quick-release 3-pointers, always hunting for the spots where he knows he can elevate and hit his shot. Damien Lillard played well enough on offense to give C.J. room to maneuver, which seems to be part of the season’s overall design. And the bench continues to gain in confidence and cohesion. There was a great play towards the end of the game when Dennis Smith, Jr. took a C.J. Elleby outlet and made a touch pass to Greg Brown for an alley-oop dunk. Everybody loves to see that.

The Blazers beat the Memphis Grizzlies, 116-96, last Wednesday night, to even their season’s record at 2 wins and 2 losses. They played excellent defense and held Ja Morant, the Grizzlies’ young star guard, to 17 points, half of what he had been averaging the first few games of the season. The Blazers had a strong second half, with more amazing dance-and-shoot moves from C.J. McCollum, who plays with astonishing grace and fluidity. He excels at step-back jumpers, mid-lane floaters, sneaky inside drives, and quick-release 3-pointers, always hunting for the spots where he knows he can elevate and hit his shot. Damien Lillard played well enough on offense to give C.J. room to maneuver, which seems to be part of the season’s overall design. And the bench continues to gain in confidence and cohesion. There was a great play towards the end of the game when Dennis Smith, Jr. took a C.J. Elleby outlet and made a touch pass to Greg Brown for an alley-oop dunk. Everybody loves to see that.

Again, the question arises: Is this the real team? Or maybe the question should be instead: Is there even such a thing as “the real team”? It seems every other franchise in the league has already had at least one truly great game, and at least one shocking clunker. Every fan now has good reason to hope their team can make a championship run, if their guys can just play the way they played in that one game… And also, every fan now has good reason to fear the whole thing could collapse in a second, and their team tumble into the bottom ranks, especially should one of their key players gets injured, which in the NBA in recent years has felt like a matter of “when” rather than “if.”

None of this made any apparent impact on my dreaming imagination that night. Instead of dreaming about the game, I dreamed about the experience of attending and watching the game with other fans:

Jane Fonda at the Center

A group is helping Jane Fonda with something inside a place….She is happy, being treated like a VIP….Everyone is trying to take good care of her, she is smiling in the center of it all….

(10/27/21)

The dream quickly brought to my mind two aspects of the game-attendance experience I had noted the previous night. First, the efficient staff at Moda Center, from ushers to security staff to entertainers to servers, all of whom have been doing an excellent job of making people feel happy and well-treated, like VIPs. Second, the shameless antics in which people will engage to attract the attention of the television cameras, with the ultimate goal of simultaneously performing and seeing oneself performing on the jumbotron screens hanging over the center of the arena. To give people the feeling of being a happy VIP at the center of it all—that’s clearly considered by fans and stadium alike as a highly desirable feature of attending a Blazers game. Live and let live, I usually say to myself during a break in the on-court action when the TV cameras roam through the crowd to find the most wildly dressed and/or dancing people for their three seconds on the jumbotron. What do I care if the world is sinking into a vortex of narcissism, and people are lost in screen-mediated labyrinths of their own egos? So what? No harm, no foul. The game will start again in a few seconds….

This whisper of misanthropic negativity towards my fellow Blazer fans seems to have evoked later that night a surprising dream response, in the form of Jane Fonda. I can say with confidence that I have never dreamed of Jane Fonda before. Nor does she appear often in other people’s dreams (just 1 reference in the 30K+ dream reports of the SDDb). Yet here she is at the center of my dream the night following an excellent, highly satisfying Blazers victory.

Hmm….

An unusual, anomalous character like this raises the question, why her rather than anyone else? What are the qualities of Jane Fonda, in my own mind at least, that make her a singular figure?

Overall, I suppose I have a positive impression of Jane Fonda. In fact, I’d say I admire her. She’s a very talented actress, a cultural innovator, a passionate advocate, a courageous risk-taker, a source of surprise and wonder. She is physically beautiful and has remained so throughout her life. She has courted controversy, defied authorities, and made very public mistakes. Some people find her unbearably annoying.

Hmm….

Would I describe her as a narcissist? That seems too harsh. But I would say she has a very healthy and robust sense of her own importance, which seems consistent with what transpires and how she behaves in my dream.

Aha!

Maybe Jane Fonda embodies a spirit of courageous creativity that I admire, even if it generates flak and friction from others—myself included. Can I recognize that same spirit in the Blazer fans around me? Can I stop rolling my eyes and appreciate their creative energy, too? Their unusual talents and risk-taking aesthetics? Their willingness to provide others with three seconds of surprise and wonder?

That makes sense and feels like it carries forward the energy of the dream. And yet, it does seem like there’s more….

Hmm….

Okay. Can I also recognize my own yearning for public attention here? My inner Jane Fonda, my unconscious desire to be a VIP at the center of everything, smiling and happy? Can I turn the critical analysis of my fellow fans around and see how I am projecting my concerns onto them? Am I anxious about my own fortunate status as a “VIP,” by being able to attend so many games this season? Yes, that’s in there, too.

Two nights later, the Blazers hosted the Los Angeles Clippers, who had crushed Portland by 30 points. This would be a chance for the Blazers to show they can bounce back from that kind of loss. And they did, beating the Clippers 111-92 in convincing fashion, even though their star forward Paul George III scored 42 points. Damien Lillard played his best game of the season, scoring 25 points to go with 6 assists. A winning brand of Blazers basketball is emerging: good team defense, hustle rebounding, a deep bench, and so many offensive weapons that someone is bound to have a hot hand. It was a very entertaining game, and promising for the future of the season.

That night I had a dream that carried forward the theme from the previous one:

The VIPs Behind Me

I going to my seat at the Blazers game, and there are complications and confusing aspects with the ticket and my phone….hmm, this is stressful….but I get there, it is all going to be good….But several other people, VIPs, one of them former President Trump, have come up behind me, and they want to pass me and go ahead….I say no, you have to wait, we will all get there in time….

(10/29/21)

I did have phone troubles at home before game, trying to get my ticket to appear on the screen. Everything was fine once I got to the game, but I must admit I felt very anxious waiting in line at the arena, because what if it happens again? That’s a very uncomfortable prospect, of fumbling with my phone while other people wait in line behind me, growing increasingly frustrated. A true nightmare.

Hmm….

It suddenly made me think of waiting in line to get on an airplane, the same feeling of anxiously making sure my papers and documents are in order, standing in a closely-packed crowd of people with whom I am about to share several hours in an enclosed space. Trying to be diplomatic, managing my own discomfort, biting my tongue at the rudeness of some of those around me, keeping an eye open for possible bogeys who might snap and cause serious disruption…. And yet unlike an airplane, the people coming into the arena are expecting to yell and scream, not sit quietly; to express their individual passions, not comply with federal regulations; to drink as much as they want and eat as much as they want and get up and down as much as they want.

Hmm….

The ex-President’s appearance adds metaphorically to the feeling of an increasingly rowdy, mostly male crowd wanting something it believes it is owed and yet being unfairly denied. And I’m blocking them, slowing them down, standing in their way.

Hmm….

The dream does suggest that there is a potential for all fans to get what they desire, if they can just show a little patience. The line is moving, slowly but surely. My troubles have been fixed, and everyone will arrive where they need to go in plenty of time. I say this to all the other people who act as if they are VIPs and should get special treatment, at Moda Center and elsewhere; I also say this to myself, insofar as the ex-President represents at some level my own selfish impatience in these situations, my own temptation towards arrogant, boorish VIP behavior. Whoever we are, however fast we move, wherever we sit, and whatever we do when we get there, can we all come together as fans to enjoy the game?

The day before the opening game of the Trailblazers’ 2021-2022 season, I was bothered by something I read online about Damien Lillard, Portland’s best player. The article ranked him lower among the league’s top players than I think he deserves; it dinged him for his defense, and emphasized the catastrophe that would befall the Blazers should he ever leave. The tone of the article reflected the very low expectations people seem to have for Portland’s performance this season. The Blazers hired a new head coach, Chauncey Billups, who has never held that role before, but whose previous assistant coaching focused on defense, and that’s where the Blazers most needed to improve (tied for 3rd best team in the league in offensive efficiency last year, but 19th in the league in defensive efficiency). Otherwise, Portland made no big roster moves during the off-season. They let Carmelo Anthony go, which I thought was too bad, he had a great run with the Blazers the past couple years. They re-signed their big mid-season acquisition from last year, shooting guard Norman Powell, which is certainly good. They added several new players to the bench, including two big guys who play great defense, Cody Zeller and Larry Nance, Jr.

The day before the opening game of the Trailblazers’ 2021-2022 season, I was bothered by something I read online about Damien Lillard, Portland’s best player. The article ranked him lower among the league’s top players than I think he deserves; it dinged him for his defense, and emphasized the catastrophe that would befall the Blazers should he ever leave. The tone of the article reflected the very low expectations people seem to have for Portland’s performance this season. The Blazers hired a new head coach, Chauncey Billups, who has never held that role before, but whose previous assistant coaching focused on defense, and that’s where the Blazers most needed to improve (tied for 3rd best team in the league in offensive efficiency last year, but 19th in the league in defensive efficiency). Otherwise, Portland made no big roster moves during the off-season. They let Carmelo Anthony go, which I thought was too bad, he had a great run with the Blazers the past couple years. They re-signed their big mid-season acquisition from last year, shooting guard Norman Powell, which is certainly good. They added several new players to the bench, including two big guys who play great defense, Cody Zeller and Larry Nance, Jr. It’s more than a metaphor to say that Halloween is a time when our nightmares go on parade. The scary images, decorations, and costumes that take over the month of October have a direct psychological connection to the actual themes and patterns of people’s nightmares. If we look at current research on nightmares—who has them, what they’re about, what causes them—we can gain new insight into the unconscious creativity of our Halloween festivities.

It’s more than a metaphor to say that Halloween is a time when our nightmares go on parade. The scary images, decorations, and costumes that take over the month of October have a direct psychological connection to the actual themes and patterns of people’s nightmares. If we look at current research on nightmares—who has them, what they’re about, what causes them—we can gain new insight into the unconscious creativity of our Halloween festivities. Earlier this week I attended the preseason basketball game between the Portland Trailblazers and the Sacramento Kings. Although the Blazers played with lots of energy, the Kings beat them handily, 107-93. That night (it was a Monday), I had the following dream:

Earlier this week I attended the preseason basketball game between the Portland Trailblazers and the Sacramento Kings. Although the Blazers played with lots of energy, the Kings beat them handily, 107-93. That night (it was a Monday), I had the following dream: Despite the many crises afflicting the world right now, or perhaps because of them, my Muses have been quite active recently. Urgent, even. They have inspired several writing projects I hope to share soon.

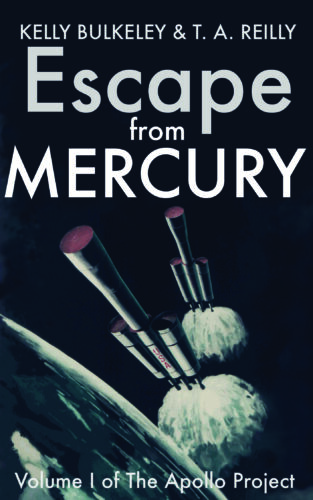

Despite the many crises afflicting the world right now, or perhaps because of them, my Muses have been quite active recently. Urgent, even. They have inspired several writing projects I hope to share soon.  Escape from Mercury – a science-fiction novel, co-edited with T.A. Reilly, in production with a private publisher, to be released on 1/1/22 at 13:00 ICT. The novel portrays an alternate history in which NASA launches a manned mission to the planet Mercury on December 3, 1979, using Apollo-era rocketry that was specifically designed for post-Lunar flights. In the present “real” timeline, those plans were abandoned. The novel reimagines the US space program continuing onward and aggressively pushing beyond the Moon, and suddenly discovering dimensions of our interplanetary neighborhood unforeseen by any but the darkest of Catholic demonologists. “The Exorcist in Space” is the tagline.

Escape from Mercury – a science-fiction novel, co-edited with T.A. Reilly, in production with a private publisher, to be released on 1/1/22 at 13:00 ICT. The novel portrays an alternate history in which NASA launches a manned mission to the planet Mercury on December 3, 1979, using Apollo-era rocketry that was specifically designed for post-Lunar flights. In the present “real” timeline, those plans were abandoned. The novel reimagines the US space program continuing onward and aggressively pushing beyond the Moon, and suddenly discovering dimensions of our interplanetary neighborhood unforeseen by any but the darkest of Catholic demonologists. “The Exorcist in Space” is the tagline. 2020 Dreams – a digital project co-authored with Maja Gutman, under contract with Stanford University Press as part of their new Digital Projects Program. We are looking at a large collection of dreams that people experienced during the year 2020, and using a variety of cutting-edge tools of data analysis and visualization to highlight patterns in the dreams and their meaningful connections to major upheavals in collective life–the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental disasters, protests for social justice, and the US Presidential election. We have just reached an agreement with the Associated Press (AP) to use their news data from 2020 as our waking-world comparison set. Our hope is to expand on the findings of Charlotte Beradt and others who have shown how dreams can reflect the impact of collective realities on individual dreams, thus providing a potentially powerful tool of social and cultural analysis.

2020 Dreams – a digital project co-authored with Maja Gutman, under contract with Stanford University Press as part of their new Digital Projects Program. We are looking at a large collection of dreams that people experienced during the year 2020, and using a variety of cutting-edge tools of data analysis and visualization to highlight patterns in the dreams and their meaningful connections to major upheavals in collective life–the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental disasters, protests for social justice, and the US Presidential election. We have just reached an agreement with the Associated Press (AP) to use their news data from 2020 as our waking-world comparison set. Our hope is to expand on the findings of Charlotte Beradt and others who have shown how dreams can reflect the impact of collective realities on individual dreams, thus providing a potentially powerful tool of social and cultural analysis. The Scribes of Sleep: Insights from People Who Keep Dream Journals – a non-fiction book in psychology and religious studies. Currently being written, under contract with Oxford University Press, likely publication in early 2023. This book brings together many sources of research about people who record their dreams over time, and what they learn from the practice. Seven historical figures are the primary case studies in the book: Aelius Aristides, Myoe Shonin, Lucrecia de Leon, Emanuel Swedenborg, Benjamin Bannecker, Anna Bonus Kingsford, and Wolfgang Pauli. A close look at their lives, their dreams, and their creative works (religiously, artistically, scientifically) suggests that keeping a dream journal seems to appeal to people with a certain kind of spiritual attitude towards the world. The stronger argument is that keeping a dream journal actively cultivates such an attitude….

The Scribes of Sleep: Insights from People Who Keep Dream Journals – a non-fiction book in psychology and religious studies. Currently being written, under contract with Oxford University Press, likely publication in early 2023. This book brings together many sources of research about people who record their dreams over time, and what they learn from the practice. Seven historical figures are the primary case studies in the book: Aelius Aristides, Myoe Shonin, Lucrecia de Leon, Emanuel Swedenborg, Benjamin Bannecker, Anna Bonus Kingsford, and Wolfgang Pauli. A close look at their lives, their dreams, and their creative works (religiously, artistically, scientifically) suggests that keeping a dream journal seems to appeal to people with a certain kind of spiritual attitude towards the world. The stronger argument is that keeping a dream journal actively cultivates such an attitude…. Here Comes This Dreamer: Practices for Cultivating the Spiritual Potentials of Dreaming – a non-fiction book addressed to general readers interested in deeper explorations of their dreaming. Currently being written, under contract with Broadleaf Books, likely publication in the latter part of 2023. The challenge here, both daunting and exciting, is explaining the best findings from current dream research in terms that “curious seekers” will find meaningful and personally relevant. The book will have three main sections: 1) Practices of a Dreamer, 2) Embodied Life, and 3) Higher Aspirations. The title of the book signals a key concern I want to highlight: to be a big dreamer, like Joseph in the Bible (Gen. 37:19), can be amazing and wonderful, but it can also be perceived by others as threatening and dangerous. Sad to say, the world does not always appreciate the visionary insights of people who naturally have vivid/frequent/transpersonal dreams. I want to share what I hope are helpful and reassuring ideas about how to stay true to your innate dreaming powers while living in a complex social world where many people are actively hostile to the non-rational parts of the mind.

Here Comes This Dreamer: Practices for Cultivating the Spiritual Potentials of Dreaming – a non-fiction book addressed to general readers interested in deeper explorations of their dreaming. Currently being written, under contract with Broadleaf Books, likely publication in the latter part of 2023. The challenge here, both daunting and exciting, is explaining the best findings from current dream research in terms that “curious seekers” will find meaningful and personally relevant. The book will have three main sections: 1) Practices of a Dreamer, 2) Embodied Life, and 3) Higher Aspirations. The title of the book signals a key concern I want to highlight: to be a big dreamer, like Joseph in the Bible (Gen. 37:19), can be amazing and wonderful, but it can also be perceived by others as threatening and dangerous. Sad to say, the world does not always appreciate the visionary insights of people who naturally have vivid/frequent/transpersonal dreams. I want to share what I hope are helpful and reassuring ideas about how to stay true to your innate dreaming powers while living in a complex social world where many people are actively hostile to the non-rational parts of the mind.  People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.

People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.