Writing has always been a relational process for me. Relationships with an imagined audience, with the people who have taught and influenced me, sometimes with co-authors, and always with the energies of inspiration I personify as Muses—without them, I would never care enough to put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard. With them, I’ve found lifelong joy and a singular sense of purpose in crafting ideas into tapestries of written language that can be shared with others.

Writing has always been a relational process for me. Relationships with an imagined audience, with the people who have taught and influenced me, sometimes with co-authors, and always with the energies of inspiration I personify as Muses—without them, I would never care enough to put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard. With them, I’ve found lifelong joy and a singular sense of purpose in crafting ideas into tapestries of written language that can be shared with others.

Not just writing, but writing about dreams: that’s always been my focus. The subject of dreaming has proven an inexhaustible wellspring of creative motivation. Writer’s block has never been a problem; there are so many interesting aspects of dreaming, so many innovative ways of exploring dreams and helping others understand their meanings, that my biggest worry is not having enough time to write all I feel capable of producing.

As I consider the list of works I still hope to write, it seems a good time to re-consider the books I’ve already written. Each one has organically flowed from the one before it, which may not be obvious to readers but has certainly shaped my approach in every instance.

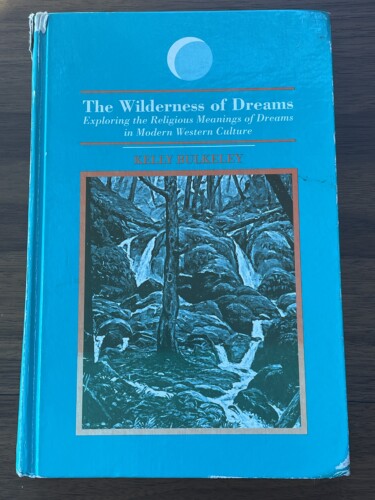

My first book, The Wilderness of Dreams, was my doctoral dissertation from the University of Chicago Divinity School, which I completed in 1992. The dissertation was, at its core, addressed to the four members of my doctoral committee: Don Browning and Peter Homans, who together formed the Religion and Psychological Studies department at the Divinity School; Wendy Doniger, of the History of Religions department at the Divinity School, and Bertram Cohler, a practicing psychoanalyst and chair of the Human Development Committee at the University of Chicago. Each of them was a brilliant scholar who deeply influenced the book, even if the topic of dreaming was not a primary concern for any of them. That turned out to be both a blessing and a curse; a blessing, because I had relative freedom to follow my instincts and develop my own approach; a curse, because I had no single mentor who really knew or understood what I was trying to do. And to be honest, I didn’t really know what I was trying to do, either. But even at that earliest stage of my career, I trusted my Muses to point me in the right direction, and I’ve never regretted that decision.

All four of my committee members were very supportive of the dissertation and encouraged me after graduation to seek a publisher for it. The State University of New York (SUNY) Press had recently launched a series in Dream Studies, with Robert Van de Castle as series editor, and I was very fortunate to enter the dream studies field at this moment. The manuscript was accepted with only a handful of editorial changes and published by SUNY in 1994.

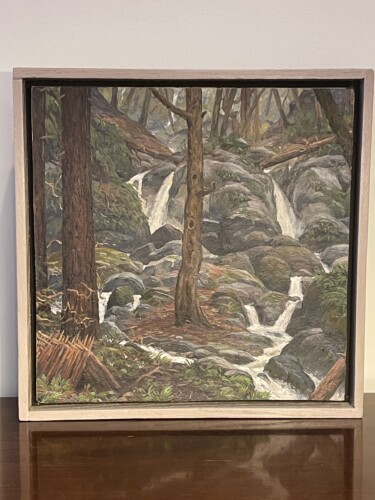

It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend Josh Adam, who has become one of the great landscape painters of our generation. Generous back-cover endorsements were provided by Jeremy Taylor and Tore Nielsen, a Unitarian-Universalist Minister and neuroscientist respectively, which was helpful in establishing the interdisciplinary credibility I was seeking.

It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend Josh Adam, who has become one of the great landscape painters of our generation. Generous back-cover endorsements were provided by Jeremy Taylor and Tore Nielsen, a Unitarian-Universalist Minister and neuroscientist respectively, which was helpful in establishing the interdisciplinary credibility I was seeking.

The guiding metaphor in the book’s structure is the idea of dreaming as a kind of wilderness that has been explored in modern times along eight different paths, each of which reveals important topographical features but none of which provides an overall understanding of the terrain. Eight figures and their works stood for these eight paths: Sigmund Freud for psychoanalysis, Andre Breton for surrealism, Carl Jung for analytical psychology, Calvin Hall for content analysis, J. Allan Hobson for neuroscience, Stephen LaBerge for lucid dreaming, Barbara Tedlock for anthropology, and Harry Hunt for cognitive psychology. An initial review highlighted both the values of each approach and their mutual incompatibility. This, I argued, poses a problem for the field of dream studies because we can hardly expect others to take our findings seriously if these findings fundamentally contradict each other. The interdisciplinary nature of dream research was a big theme here: we need multiple disciplines to do justice to the full complexity of dreaming experience, but we also need to find a way to integrate these different perspectives or else we risk collapsing into incoherence and irrelevance.

In an effort to overcome these contradictions, each of the approaches was analyzed in light of its stance on 1) the nature of dream interpretation and 2) the potential religious significance of dreaming. To evaluate their ideas about dream interpretation, I relied on the hermeneutic philosophy of Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur. To assess their ideas about dreams and religiosity, I drew on George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s metaphor theory as adopted by the theologies of Don Browning and Sallie McFague. By the end of the book I developed the notion of “root metaphors” as a resource for understanding how dreams can best be understood in their religious potentiality.

Over the years, I’ve come to see this book as the starting point for virtually everything I’ve written and still hope to write. The interdisciplinary nature of dream research, the deep connection between dreaming and the environment, the playful dynamics of dreaming, the spiritual potentials of dreams for both individual and collective transformation—all these themes are still resonant in my work today, more than thirty years later. Maybe I’m just stuck in the world’s biggest rut! But maybe I’ve been right to trust my Muses and follow them where they lead.

Houses and homes are among the most frequent elements appearing in dreams, with a wide range of literal and symbolic meanings.

Houses and homes are among the most frequent elements appearing in dreams, with a wide range of literal and symbolic meanings. Construction is going well so far on the Dream Library, a stand-alone structure on a rural, forested property near Portland, Oregon. As many friends and colleagues know, the project has taken a long time to reach this stage, but at last it’s beginning to take actual shape. The building will provide a long-term archive for dream-related materials such as journals, books, and art. The journal & book collections of Jeremy Taylor and Patricia Garfield will form the core of the library, along with other donated materials and my own collections.

Construction is going well so far on the Dream Library, a stand-alone structure on a rural, forested property near Portland, Oregon. As many friends and colleagues know, the project has taken a long time to reach this stage, but at last it’s beginning to take actual shape. The building will provide a long-term archive for dream-related materials such as journals, books, and art. The journal & book collections of Jeremy Taylor and Patricia Garfield will form the core of the library, along with other donated materials and my own collections.

The bizarre contents of dreaming can easily seem like the products of mental deficiency. “Children of an idle brain” is what Mercutio calls them in Romeo & Juliet (I.iv.102). Many scientists today essentially agree with Mercutio that the weird absurdities of dreams are evidence of diminished cognitive functioning during sleep.

The bizarre contents of dreaming can easily seem like the products of mental deficiency. “Children of an idle brain” is what Mercutio calls them in Romeo & Juliet (I.iv.102). Many scientists today essentially agree with Mercutio that the weird absurdities of dreams are evidence of diminished cognitive functioning during sleep. The neuroscience of dreams has shifted in recent years toward the idea that dreaming can be conceived as a kind of mind-wandering in sleep. According to current evidence, mind-wandering (also known as day-dreaming, or drifting thought) is a product of the “default mode network,” a system of neural regions that remains active in the absence of external stimulus or focused thought. During sleep this same system of neural regions becomes active, helping to generate the experience of dreaming.

The neuroscience of dreams has shifted in recent years toward the idea that dreaming can be conceived as a kind of mind-wandering in sleep. According to current evidence, mind-wandering (also known as day-dreaming, or drifting thought) is a product of the “default mode network,” a system of neural regions that remains active in the absence of external stimulus or focused thought. During sleep this same system of neural regions becomes active, helping to generate the experience of dreaming. This is a post I recently wrote about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in the practice of dream interpretation. In coordination with the team at the Elsewhere.to dream journaling app–Dan Kennedy, Gez Quinn, and Sheldon Juncker–we have been experimenting with “Freudian” and “Jungian” modes of interpretation, and the results are very encouraging. Maybe more than encouraging… I don’t highlight this in the post, but the AI interpretation in “Jungian” mode used the phrase “confrontation with the unconscious,” which was not part of the prompting text for the AI. In other words, the AI seems to have identified this phrase as a vital one in Jungian psychology (it’s the title of the pivotal chapter 6 of his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections) and, without any direct guidance, used it accurately and appropriately in an interpretation . I might even suspect a sly irony in using this phrase in reference to a dream of Freud’s, but that might be too much…

This is a post I recently wrote about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in the practice of dream interpretation. In coordination with the team at the Elsewhere.to dream journaling app–Dan Kennedy, Gez Quinn, and Sheldon Juncker–we have been experimenting with “Freudian” and “Jungian” modes of interpretation, and the results are very encouraging. Maybe more than encouraging… I don’t highlight this in the post, but the AI interpretation in “Jungian” mode used the phrase “confrontation with the unconscious,” which was not part of the prompting text for the AI. In other words, the AI seems to have identified this phrase as a vital one in Jungian psychology (it’s the title of the pivotal chapter 6 of his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections) and, without any direct guidance, used it accurately and appropriately in an interpretation . I might even suspect a sly irony in using this phrase in reference to a dream of Freud’s, but that might be too much…