Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, and in honor of his birthday I am reposting a brief essay about four dreams he reportedly experienced while President: a visitation dream, a dream of parental concern, a prophecy of his assassination, and a series of dreams relating to military battles. Each of these dreams is reported in a legitimate historical source, indicating that Lincoln took dreams very seriously and tried to incorporate their insights into his waking life.

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, and in honor of his birthday I am reposting a brief essay about four dreams he reportedly experienced while President: a visitation dream, a dream of parental concern, a prophecy of his assassination, and a series of dreams relating to military battles. Each of these dreams is reported in a legitimate historical source, indicating that Lincoln took dreams very seriously and tried to incorporate their insights into his waking life.

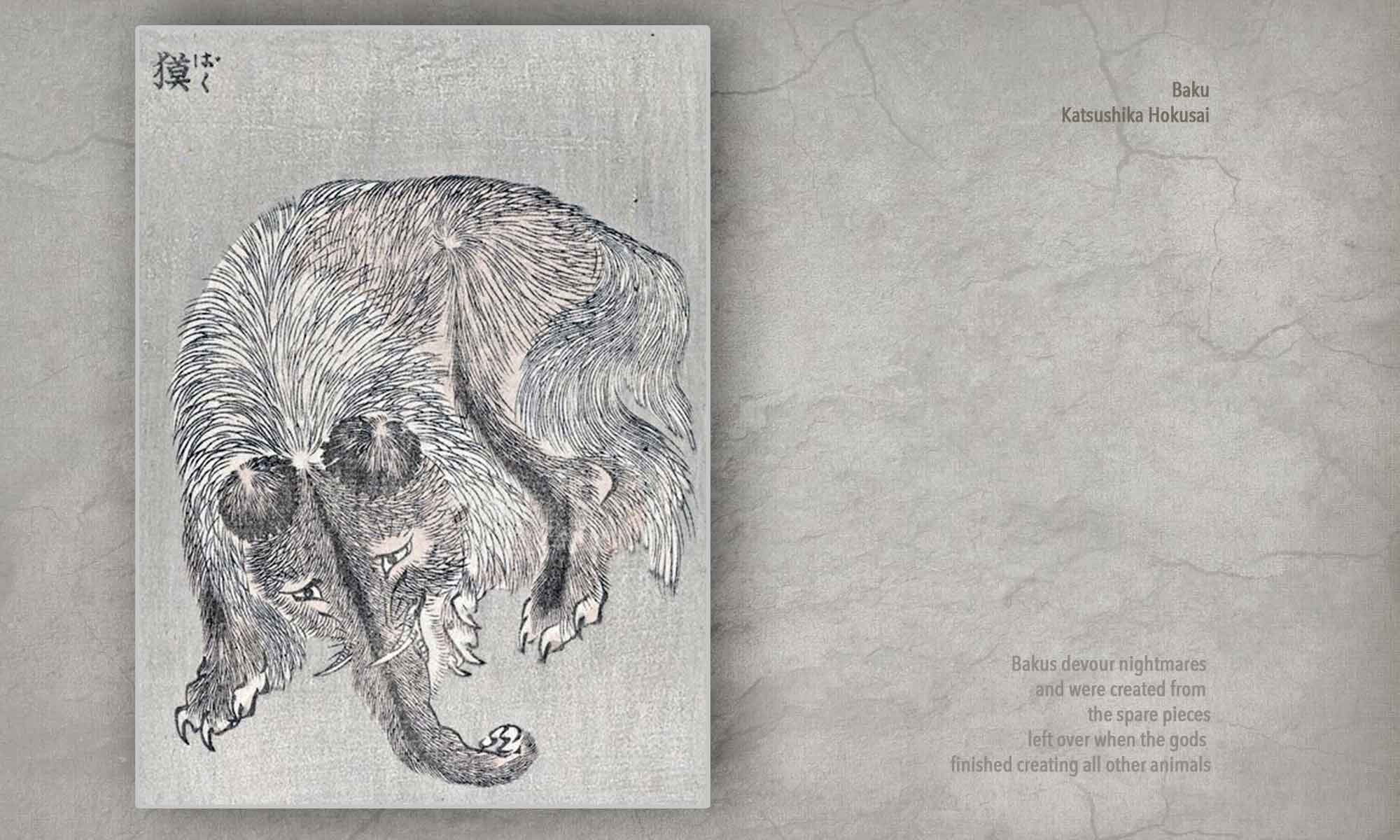

Abraham Lincoln 1: Visitation of the Dead

“Mr. Lincoln said: ‘Colonel, did you ever dream of a lost friend, and feel that you were holding sweet communion with that friend, and yet have a sad consciousness that it was not a reality?—just so I dream of my boy Willie.’ Overcome with emotion, he dropped his head on the table, and sobbed aloud.”

Henry J. Raymond, The Life of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Darby and Miller, 1865), 756.

Abraham Lincoln, elected President of a rapidly fragmenting country in 1860, reportedly confided this dream to in the spring of 1862 to his personal aide, Colonel Le Grand B. Cannon. Just a few months earlier Lincoln’s son Willie had died, at the age of eleven. Willie was the second son he and his wife Mary had lost (four-year old Eddie died in 1850). Visitation dreams of deceased loved ones have been reported in many cultures around the world, reflecting the all-too-human desire to look beyond death and meet with those who have left their physical bodies. Lincoln commented on the paradoxical quality of his experience, which I’ve found characteristic of many visitation dreams: they are joyful and heartbreaking, reassuring and distressing at the same time. The vivid memorability of such dreams plays an important role in the mourning process, enabling the individual to envision a new kind of relationship with the dead person—an enduring spiritual connection of tremendous emotional power that carries over from dreaming into waking awareness. Whether or not you believe such dreams represent the wishful imaginings of the mind or the actual contact between a living person and a soul of the dead, visitation dreams provide people with a kind of sad wisdom that’s profoundly reassuring, particularly in times of waking-life conflict and danger. That would certainly describe the situation Lincoln faced in 1862. The Civil War had begun the previous year, and he felt the unimaginable weight of personal responsibility for the country’s political survival. As painful as these dreams of his dead son Willie may have been, I suspect Lincoln wouldn’t have given them up for anything.

Abraham Lincoln 2: Parental Concern

“Think you better put “Tad’s” pistol away. I had an ugly dream about him.”

Abraham Lincoln, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953), Volume 6, Note of June 9, 1863.

Lincoln sent this brief note to his wife Mary regarding their youngest son Tad, ten years old at the time. No details are given about this “ugly dream,” and apparently no details were required. Mary would have immediately understood her husband’s worry, accepted its source, and taken the necessary precautions. Lincoln’s parental anxiety dream, in today’s language, represented “actionable intelligence.” Mary took great interest in dreams and other kinds of unusual psycho-spiritual phenomena, and historians have blamed her for her husband’s dalliances with the supernatural. But I think we should credit Lincoln with possessing at least as much innate dreaming power as any other human, including the capacity of his nocturnal imagination to simulate realistic threats to himself and his family. The psychological potency of dreaming appears very clearly in Lincoln’s brief report. The “ugly dream” provoked greater awareness of a danger to one of his children, and it prompted greater vigilance in his waking life to defend against that danger.

Abraham Lincoln 3: Who Is Dead in the White House?

“About ten days ago I retired very late. I had been up waiting for important dispatches from the front. I could not have been long in bed when I fell into a slumber, for I was weary. I soon began to dream. There seemed to be a death-like stillness about me. Then I heard subdued sobs, as if a number of people were weeping. I thought I left my bed and wandered downstairs. There the silence was broken by the same pitiful sobbing, but the mourners were invisible. I went from room to room; no living person was in sight, but the same mournful sounds of distress met me as I passed along. It was light in all the rooms; every object was familiar to me; but where were all the people who were grieving as if their hearts would break? I was puzzled and alarmed. What could be the meaning of all this? Determined to find the cause of a state of things so mysterious and so shocking, I kept on until I arrived at the East Room, which I entered. There I met with a sickening surprise. Before me was a catafalque, on which rested a corpse wrapped in funeral vestments. Around it were stationed soldiers who were acting as guards; and there was a throng of people, some gazing mournfully upon the corpse, whose face was covered, others weeping pitifully. ‘Who is dead in the White House?’ I demanded of one of the soldiers. ‘The President,’ was his answer; ‘he was killed by an assassin!’ Then came a loud burst of grief from the crowd.”

Stephen B. Oates, With Malice Toward None: A Life of Abraham Lincoln (New York: HarperPerennial, 1994), 425-426

During the second week of April 1865, a few days before his assassination, Lincoln told this dream to his wife, his bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon, and one or two other people sitting with him in the White House. According to Lamon, who wrote down the conversation immediately afterwards, a downcast Lincoln said the weird dream had haunted and possessed him for the past several days. Mary and Lamon both became alarmed at the ominous implications, and Lincoln tried to reassure them by saying it probably meant nothing. He doesn’t seem to have believed that himself, though. Death by assassination was a real and constant threat; Lincoln knew for a fact that Southern sympathizers were plotting to kill him. He also knew from his close reading of Shakespeare and the Bible that especially memorable dreams can portend the imminence of death. His earlier night visions focused on the well-being of his children, but now his dreaming imagination turned to the dangers looming over his own life.

After Lincoln was shot the night of April 14, an anguished Mary was heard to exclaim , “His dream was prophetic!”

Abraham Lincoln 4: Victory

“At the Cabinet meeting held the morning of the assassination, it was afterward remembered, a remarkable circumstance occurred. General Grant was present, and during a lull in the discussion the President turned to him and asked if he had heard from General Sherman. General Grant replied that he had not, but was in hourly expectation of receiving dispatches from him announcing the surrender of Johnston. ‘Well,’ said the President, ‘you will hear very soon now, and the news will be important.’ ‘Why do you think so?’ said the General. ‘Because,’ said Mr. Lincoln, ‘I had a dream last night; and ever since the war began, I have invariably had the same dream before any important military event occurred.’ He then instanced Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, etc., and said that before each of these events, he had had the same dream; and turning to Secretary [of the Navy] Welles, said: ‘It is in your line, too, Mr. Welles. The dream is, that I saw a ship sailing very rapidly; and I am sure that it portends some important national event.’”

Francis Carpenter, Six Months at the White House with Abraham Lincoln: The Story of a Picture (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1866), 292.

Here’s an instance of pre-battle dreaming, an apparently frequent occurrence in Lincoln’s life as military commander of the Northern army. He had learned to associate the dreaming image of a ship speeding across the sea with the imminent arrival of momentous news, and on this Good Friday morning of 1865 he felt the impulse to share his dream omens with his military commanders. The final triumph of the Union over the Confederacy lay just weeks away, and Lincoln knew the war had been won. His optimism seems tragically misplaced in light of his murder that very night, but I’m more interested in his imparting of oneiric wisdom to the victorious generals. In speaking so openly about his dreams as legitimate sources of warning and knowledge that helped him in his efforts to keep the Union together, Lincoln offered the generals gathered around him (whose company included Ulysses S. Grant, the man who would be President from 1869-1877) an example of truly visionary leadership. He also offered to the rest of American history an example of someone who relied on his dreams to help him overcome the most serious challenges in both his personal and collective life.

But Lincoln did not say…

“My dream is of a place and a time where America will once again be seen as the last, best hope of earth.”

This quote is often attributed to Abraham Lincoln, but that’s apparently incorrect. I could not find it in any of Lincoln’s known writings, and several Lincoln scholars agreed that the sentence is apocryphal. The last six words, without the comma, appeared at the conclusion of Lincoln’s address to the U.S. Congress on December 1, 1862. The meaning and spirit of his actual words point to an idealistic hope for America’s future that has long (but not that long) been associated with a special kind of dream:

“We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it. We, even we here, hold the power and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave we assure freedom to the free–honorable alike in what we give and what we preserve. We shall nobly save or meanly lose the last best hope of earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail. The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just–a way which if followed the world will forever applaud and God must forever bless.”

An excellent guest post on Ryan Hurd’s Dream Studies website by A.L. Castonguay looks at sleep as a misunderstood public health issue. Specifically, who in America is sleeping relatively well, and who is sleeping poorly? The latter group is important to identify because inadequate sleep can lead to physical, emotional, and cognitive problems–not to mention disrupted, diminished dreaming.

An excellent guest post on Ryan Hurd’s Dream Studies website by A.L. Castonguay looks at sleep as a misunderstood public health issue. Specifically, who in America is sleeping relatively well, and who is sleeping poorly? The latter group is important to identify because inadequate sleep can lead to physical, emotional, and cognitive problems–not to mention disrupted, diminished dreaming.