Sleep is both a gentle source of earthly pleasure and a stressful battlefield of military violence in Shakespeare’s stirring portrait of a young Prince.

The play opens with Henry IV, the 15th century English King, planning his military strategy against various enemies who are threatening rebellion. One of the rebel leaders is Henry “Hotspur” Percy, the Earl of Northumberland’s valiant son whose battlefield exploits have become legendary. As the King reflects on Hotspur’s noble deeds, he cannot ignore the painful contrast with his own unruly, disobedient son, Prince Henry or “Hal,” who wastes his time in “riot and dishonor” with a lowlife gang of drunkards, thieves, and scoundrels. The King’s first mention of his child is a wish to be rid of him:

O that it could be proved

That some night-tripping fairy had exchanged

In cradle clothes our children where they lay,

And called mine Percy, and his Plantagenet!

Then I would have his Harry, and he mine. (I.i.88-92)

In many cultures around the world, including early modern England, people have been terrified by the evil spirits that strike infants in their sleep. To protect their children, parents have used prayers, rituals, amulets, and holy artifacts to ward off the malevolent beings who attack newborns during the dark of night. In this context, it would be shocking for a parent to actively wish that a “night-tripping fairy” would come to steal his true child. By so wishing, the King reveals the cruel extremity of his detachment from young Henry.

The next scene introduces Prince Hal’s scurrilous but intimate group of friends, led by Sir John Falstaff, a man of grand humor and bottomless appetites. Hal’s first words make this clear: “Thou art so fat-witted, with drinking of old sack and unbuttoning thee after supper and sleeping upon benches after noon” (I.ii.2-4). Here is a neat list of Falstaff’s chief vices, which include a gluttonous desire for sleep. Falstaff enjoys sleeping for the same reason he enjoys drinking and whoring—they feel good. But he denies the Prince’s moral condemnation of his chosen way of life, now and in the future:

“When thou art King, let not us that are squires of the night’s body be called thieves of the day’s beauty. Let us be Diana’s foresters, gentlemen of the shade, minions of the moon; and let men say we be men of good government, being governed as the sea is, by our noble and chaste mistress the moon, under whose countenance we steal.” (I.ii.23-30)

Even though Falstaff is speaking in prose, his words have a roguish poetry. He casts himself as a member of a mystical lunar guild; he breaks the laws of the daytime not because he is a base criminal, but because he is a true and faithful servant of the “mistress the moon.”

Hal knows that Falstaff is no such thing, but he also knows the fun of hanging around with Falstaff is listening to him spin out absurd stories and fanciful lies. Even more fun is playing a trick on Falstaff to provoke his boundless capacity for creative falsehoods. Such an opportunity arises when Poins, a renowned highway robber, arrives and tells them of an excellent opportunity for profitable thievery. A group of rich pilgrims will be traveling on a nearby road in the pre-dawn darkness, and it would be easy to ambush them and separate them from their valuables. Poins declares, “We may do it as secure as sleep” (I.ii.132-133).

This analogy emphasizes the simplicity of the plan. Just as it’s easy to go to sleep, it will be easy to rob the pilgrims. Falstaff accepts this metaphorical reasoning, given how quickly and comfortably he can fall sleep (more on this in a moment). Yet the analogy has another layer of meaning that Falstaff does not recognize, of sleep as a descent into a world of darkness and disorientation with strange reversals of identity and startling discoveries of truth and deception. Falstaff doesn’t know it, but Poins soon confides to Hal that the real plan is to trick Falstaff during the robbery. To be “as secure as sleep” will turn out to be not very secure at all.

What ensues is one of the greatest scenes in literature as Hal and the other “minions of the moon” banter with Falstaff while he tells his thrilling, heroic, and completely fictional account of what happened during the robbery. The Prince shares the old rogue’s giddy joy in his fanciful flights of imagination. Despite their radical differences in age and station, they have this creative pleasure in common. Their playful battles of wit generate an exuberant vitality that enlivens them both.

The jesting abruptly ends when the Sheriff arrives to inquire about the robbery. Everyone scatters and hides while the Prince must resume his royal identity and assure the Sheriff the pilgrims will be repaid for what they have lost. After the Sheriff has left, Hal tells Peto to find that “oily rascal.” A moment later Peto calls out, “Falstaff! Fast asleep behind the arras, and/Snorting like a horse” (II.iv.535-536). The comedy of Peto’s discovery turns on Falstaff’s blithe lack of concern for anything but his own immediate bodily pleasure. While the Sheriff is in that very room looking to arrest him for a capital crime, Sir John lays down in a dark place and slips into a deep, beastly slumber. Unburdened by guilt or shame, having no ambition beyond the next bottle of sack, he is not even perturbed by Hal’s recent, ominous words about a future banishment (“I do, I will.”). Falstaff enjoys sleep as one of the many sumptuous courses in the great feast of life, and he lets nothing distract him from consuming his fill.

At the other end of the spectrum, the relentlessly aggressive Hotspur treats sleep as another battlefield where enemies can be attacked, fought, and conquered. In Hotspur’s opening scene he rages against the King for refusing to help his kinsman Mortimer and commanding no further discussion of it. Hotspur imagines a nocturnal assault on the arrogant monarch:

He said he would not ransom Mortimer,

Forbade my tongue to speak of Mortimer,

But I will find him when he lies asleep,

And in his ear I’ll hollo ‘Mortimer.’” (I.iii.235-236)

He may threaten to attack the King during sleep, but it’s Hotspur himself who has the most troubled slumber of anyone in the play. His wife, Lady Kate, asks him why he is so agitated and disturbed: “Tell me, sweet lord, what is’t that takes from thee/Thy stomach, pleasure, and thy golden sleep?” (II.iii.41-42) In contrast to Falstaff, Hotspur has lost all of his normal physical appetites. Lady Kate goes on to describe in sorrowful detail the frightening spectacle of her husband’s sleeping body:

In thy faint slumbers I by thee have watched,

And heard thee murmur tales of iron wars,

Speak terms of manage to thy bounding steed,

Cry ‘Courage! to the field!’ And thou has talked

Of sallies and retires, of trenches, tents,

Of palisades, frontiers, parapets,

Of basilisks, of cannon, culverin,

Of prisoners’ ransom, and of soldiers slain,

And all the currents of a heady fight.

Thy spirit within thee hath been so at war,

And thus hath so bestirred thee in thy sleep,

That beads of sweat have stood upon thy brow

Like bubbles in a late-disturbed stream,

And in thy face strange motions have appeared,

Such as we see when men restrain their breath

On some great sudden hest. O what portents are these?

Some heavy business hath my lord in hand,

And I must know it, else he loves me not. (II.iii.48-66)

Lady Kate’s account opens a window into the war-obsessed, hyper-militarized mind of Hotspur. Fighting is all he thinks about, day and night, in waking and sleeping. Her description of his physical reactions have aspects of both sleep paralysis and night terrors, which are often triggered by frightening or unsettling situations in waking life. His behavior may even reflect the repetitive nightmares symptomatic of post-traumatic stress disorder; his wartime experiences would have given him plenty of raw material. But Lady Kate is trying to emphasize how frightening it is for her to watch her beloved endure such unconscious torments—he’s sweating, he can’t breathe, he’s in obvious distress. Her plea for him to tell her what’s wrong is a plea for him to recognize the painful impact of his nocturnal suffering on her.

This passage offers the closest approximation of a full dream report available in the play. Dreams are mentioned elsewhere twice in turns of phrase (“that thou dreamst not of,” II.i.69-70; “before not dreamt of,” IV.i.78) meant to emphasize something that’s vitally important yet beyond normal reckoning. Hotspur at one point says he hates foolish talk about “the dreamer Merlin and his prophecies” (III.i.161). Besides that, the only other reference to dreaming is indirect, in the pre-battle scene where the rebel lords take leave of their ladies. Mortimer’s wife, who can only speak Welsh, invites her husband to enjoy a final, private reverie together:

She bids you on the wanton rushes lay you down

And rest your gentle head upon her lap,

And she will sing the song that pleaseth you

And on your eyelid crown the god of sleep,

Charming your blood with pleasing heaviness,

Making such difference ‘twixt wake and sleep

As is the difference betwixt day and night

The hour before the heavenly-harnessed team

Begins his golden progress in the east (III.i.230-239)

This is a beautiful image of sensual slumber, and one of the most poignant moments in the play. A woman who cannot speak her husband’s language offers to ease him into a lyrical space of soothing comfort, away from the sharp edges of waking reality. Indeed, I wonder if she is subtly helping him incubate a dream to guide him in the coming battle. The liminal state she is trying to evoke, just before dawn when sleep is about to yield to waking, is in fact the time when the human brain typically enters its peak phase of REM sleep, generating the highest frequency of remembered dreams.

What about Prince Henry? How will he sleep and dream? We do not know yet. He is still unformed, his identity still in the process of becoming. He has two more plays to go. Will he learn from Falstaff and the “gentlemen of the shade” to sleep easily and well, or will he fall prey like Hotspur to the wrenching, inescapable violence of a militarized dreamscape?

####

Contemporary performances:

Last week I saw a powerful production of Henry IV Part I at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, with Daniel Jose Molina as the young Prince, G. Valmont Thomas as Falstaff, and Alejandra Escalante as Hotspur. The scenes with Molina and Thomas were magical; at several points in their comedic jousting I had tears of laughter running down my cheeks. The intimate space of the Thomas Theater enabled both actors to draw the audience into their merry band of criminal conspirators, making everyone feel a part of their antics, adventures, and jests. I truly lost track of time during the riotous fourth scene of Act II. When the Sheriff suddenly arrived it felt like a harsh and unwanted intrusion into our fun times, like an alarm clock jarring us out of a good dream. A buzz-kill, in other words.

The casting of Escalante as Hotspur gave a fresh look at Shakespeare’s classic portrait of a young warrior, inflamed with a righteous rage for vengeance. Escalante’s intense performance decoupled Hotspur’s aggression from gender, which is perhaps another way of saying her performance humanized this aspect of Hotspur’s character. I found the effect especially strong in the scene where Lady Kate (played by Nemuna Ceesay) described Hotspur’s frightening behaviors in sleep. Escalante and Ceesay had a vibrant and mutual romantic rapport that seemed to subtly change these lines from a shameful revelation of cowardly fear into an honest admission of the burden of fighting to uphold one’s ideals. Instead of driving them apart, this deeply emotional exchange brought them closer together.

Note: this essay first appeared in the Huffington Post on April 18, 2017.

In August of 1991 I joined a group of dream researchers from the U.S. and Western Europe on a journey to Golitsyno, a conference center just outside Moscow in the former Soviet Union, where we planned to meet several Soviet researchers for a gathering organized by Jungian analyst Robert Bosnak. Just hours after our plane landed in Moscow on August 19, the airport was suddenly shut down by the Red Army; a

In August of 1991 I joined a group of dream researchers from the U.S. and Western Europe on a journey to Golitsyno, a conference center just outside Moscow in the former Soviet Union, where we planned to meet several Soviet researchers for a gathering organized by Jungian analyst Robert Bosnak. Just hours after our plane landed in Moscow on August 19, the airport was suddenly shut down by the Red Army; a

Prophetic dreams of doom go unheeded in Shakespeare’s tragedy about violent political strife among the greatest leaders of ancient Rome.

Prophetic dreams of doom go unheeded in Shakespeare’s tragedy about violent political strife among the greatest leaders of ancient Rome. What would you do if you could control not only your own dreams, but other people’s dreams, too? What if you could enter other people’s dreams without their knowing it? How would you use those powers? Do the same ethical principles that guide our waking lives also apply in dreaming?

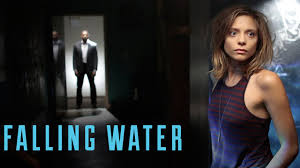

What would you do if you could control not only your own dreams, but other people’s dreams, too? What if you could enter other people’s dreams without their knowing it? How would you use those powers? Do the same ethical principles that guide our waking lives also apply in dreaming? The second episode of the excellent new TV series

The second episode of the excellent new TV series

This essay is based on a presentation I gave at the

This essay is based on a presentation I gave at the  Which brings us to “Pan’s Labyrinth.” Guillermo del Toro’s 2006 film is not purely fantasy or science fiction, but rather a surrealist fairy tale folded into a wartime drama. Maybe it should be called “historical horror.”

Which brings us to “Pan’s Labyrinth.” Guillermo del Toro’s 2006 film is not purely fantasy or science fiction, but rather a surrealist fairy tale folded into a wartime drama. Maybe it should be called “historical horror.” The fantasy sequences with Ofelia have some striking similarities with the typical content patterns of lucid dreams, as mentioned earlier. Here’s how I summarized the research findings a few minutes ago:

The fantasy sequences with Ofelia have some striking similarities with the typical content patterns of lucid dreams, as mentioned earlier. Here’s how I summarized the research findings a few minutes ago: As it turns out, there is a good biographical reason for this. In interviews he gave at the time of the film’s release, del Toro described his own childhood experiences of “lucid nightmares” in which he saw the figure of the Faun stepping out from behind a dresser at midnight. He had recurrent dreams of many kinds of monsters, but the Faun made an especially horrifying impact on him. In the film del Toro aims to recreate this powerful fantasy figure who stalked his own personal nightmares.

As it turns out, there is a good biographical reason for this. In interviews he gave at the time of the film’s release, del Toro described his own childhood experiences of “lucid nightmares” in which he saw the figure of the Faun stepping out from behind a dresser at midnight. He had recurrent dreams of many kinds of monsters, but the Faun made an especially horrifying impact on him. In the film del Toro aims to recreate this powerful fantasy figure who stalked his own personal nightmares. When del Toro referred to these dreams as “lucid” he seemed to mean they had all the qualities of waking reality, and yet he knew they were dreams because of the appearance of Faun or other creatures. It’s not that he was dreaming, then realized he was awake within the dream; rather, he felt like he was awake, while also realizing he must be dreaming. Both are paths to lucidity, but the latter can be much more frightening and existentially unsettling.

When del Toro referred to these dreams as “lucid” he seemed to mean they had all the qualities of waking reality, and yet he knew they were dreams because of the appearance of Faun or other creatures. It’s not that he was dreaming, then realized he was awake within the dream; rather, he felt like he was awake, while also realizing he must be dreaming. Both are paths to lucidity, but the latter can be much more frightening and existentially unsettling. This helps to explain at least some of the uncanny impact of “Pan’s Labyrinth.” Guillermo del Toro knows from deep personal experience the feelings of dread and terror associated with the darker path into lucidity. He knows that if you are already dreaming and then become self-aware, your conscious self feels powerful and expanded. But if you realize what you thought was waking reality is actually a dream, that’s a much more threatening mode of lucidity, a lucidity of weakness, vulnerability, and deception. A lucidity of horror.

This helps to explain at least some of the uncanny impact of “Pan’s Labyrinth.” Guillermo del Toro knows from deep personal experience the feelings of dread and terror associated with the darker path into lucidity. He knows that if you are already dreaming and then become self-aware, your conscious self feels powerful and expanded. But if you realize what you thought was waking reality is actually a dream, that’s a much more threatening mode of lucidity, a lucidity of weakness, vulnerability, and deception. A lucidity of horror.