This is the text of a paper I presented at “The Psychology of Religion/Religion of Psychology” conference held at the University of Chicago Divinity School on March 6, 2015. My paper was the first in a panel devoted to “Disjunctions Between Contemporary Psychology and Religion.”

This is the text of a paper I presented at “The Psychology of Religion/Religion of Psychology” conference held at the University of Chicago Divinity School on March 6, 2015. My paper was the first in a panel devoted to “Disjunctions Between Contemporary Psychology and Religion.”

On July 17, 1990, President George H.W. Bush announced in Proclamation 6158 that the 1990’s were to be officially designated as the “Decade of the Brain.” The Proclamation began with these lines:

“The human brain, a 3-pound mass of interwoven nerve cells that controls our activity, is one of the most magnificent—and mysterious—wonders of creation. The seat of human intelligence, interpreter of senses, and controller of movement, this incredible organ continues to intrigue scientist and layman alike.”

President Bush’s Proclamation accelerated scientific efforts to learn more about how the brain works, with a special focus on finding new treatments for devastating neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. To achieve that goal, powerful technologies were developed to analyze, measure, and influence the brain. These tools are primarily aimed at addressing the growing medical needs of an aging population, but they have been applied in other areas of research as well, including the psychological dimensions of religion.

Other speakers may talk in more detail about the positive aspects of this turn towards the brain, and so will I. But first, we should consider the casualties and costs of this historical shift, which has in many ways been disastrous for the psychology of religion. Three particular losses—of historical awareness, therapeutic engagement, and interest in mysticism—will be the focus of my presentation, which Peter Homans, who taught here at the Divinity School for many years, might have considered a work of mourning, in the sense of responding to loss by the creation of new meanings. If we can gain more clarity about what has been lost in this field since the “Decade of the Brain,” we can more fairly assess the potential benefits of neuroscientific research for religious studies. We can also, at that point, consider the potential benefits of religious studies for brain research.

Let me briefly define some terms.

The psychology of religion, as we have already heard, comprises a multifaceted research tradition going back more than 100 years to the pioneering work of Sigmund Freud, William James, Carl Jung, and others.

Cognitive science is an alliance of six disciplines—neuroscience, psychology, computer science, linguistics, philosophy, and anthropology—that together, beginning in the 1970’s and accelerating in the 1990’s, have tried to improve on psychoanalytic and behaviorist models of the mind.

The cognitive science of religion, or CSR, is a 21st century development in the psychology of religion, drawing on contemporary scientific studies of brain-mind functioning.

CSR appeals to many researchers because it emphasizes experimental evidence and testable hypotheses, helping researchers escape the hazy hermeneutics and overly thick descriptions too often found in the contemporary study of religion. CSR offers a bracing, forward-looking response to the tired and fruitless meanderings of post-modern scholarship.

Unfortunately, the cost of this approach has been a loss of interest in, or even awareness of, the findings of earlier researchers who carefully investigated many of the same topics as those found in CSR. Anything that happened before the “Decade of the Brain” no longer seems relevant now that we have such powerful neuroimaging tools at our disposal. This leads to CSR researchers claiming new explanations of phenomena that actually have a long history in the psychology of religion. This is what Jeremy Carrette has called “disciplinary amnesia,” and our field has a bad case of it.

As a brief example, consider Pascal Boyer’s 2002 book Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. This is an admirable work in many ways, and highly influential in CSR, but it takes strangely little account of earlier research in the psychology of religion. In a passage late in the book Boyer comments on the similarities between religious rituals and obsessive-compulsive disorder (or OCD). He describes several neuroscientific studies, all conducted in the 1990’s, on dysfunctions in the brain associated with OCD. Although he does not insist that all religious rituals are pathological, Boyer uses this neurological evidence to support his book’s overall argument that religious beliefs and behaviors are “parasitic” on normal processes of the mind.

I don’t want to engage right now with Boyer’s “mental parasite” theory of religion. Rather, I want to point out that in two detailed pages of text comparing religious rituals and OCD, Boyer never once mentions Freud, whose 1907 article “Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices” addressed exactly the same topic. Indeed, Freud’s prescient article was crucial in defining the clinical syndrome of OCD itself, which Boyer now “explains” in CSR terms.

Why does this loss of history matter? Maybe it doesn’t. There is an argument to be made that a scientific field should not be overly concerned with or reverential towards its past. After all, we don’t make people study alchemy before they can start learning chemistry.

But it’s not that simple in the psychology of religion. Not only does the loss of historical self-awareness lead to unwarranted claims of novel discoveries, it also makes it harder to avoid going down paths that earlier researchers have found to be dead-ends. Here again, the case of Freud is helpful. Too few people know or appreciate the fact that Freud was originally trained as a neuroscientist, receiving his education from some of the best medical research institutions in the world at that time. Freud knew as much about the brain as anyone, and in 1895 he began drafting “A Project for a Scientific Psychology,” in which he planned to use neuroscientific evidence to explain mental life in purely physical terms. But then, a couple years later, he gave up on this plan, and turned to the study of dreams. Why did Freud abandon his neuroscientific vision? Not because he lacked hi-tech brain scanners. Freud gave up on the 1895 Project because he realized that experimental neuroscience was not enough, and would never be enough, to understand the human mind. Focusing on the material workings of the brain can only take us so far, before we have to include the analysis of emotion, desire, consciousness, family, culture, and many other dimensions of psychological experience that are difficult to measure or experimentally manipulate.

Paul Ricoeur, in his 1970 book Freud and Philosophy, gave Freud credit for developing a “mixed discourse” between force and desire, energetics and hermeneutics, the workings of the brain and the meanings of the mind. Freud may have been limited in his view of those forces and desires, but he had the right idea: we need hybrid theories and concepts that can clarify, rather than obscure, the subtle, multidimensional complexities of the human psyche.

This kind of approach has been eclipsed in recent years by the emphasis on brain science as the ultimate source of explanatory truth. We seem to be going back to a place that Freud abandoned at the end of the 19th century. It’s worse than just reinventing the wheel, it’s forgetting why we ever needed a wheel in the first place.

The second loss, of therapeutic engagement, reflects another adverse consequence of the “Decade of the Brain.” Throughout the 20th century the psychology of religion was stimulated by the clinical work of Freud, Jung, and many, many other skilled therapists who delved deeply into the mental worlds of their clients, and in the process gained remarkable insights into the religious and psychological dynamics of their lived experiences. Both medical psychiatrists and pastoral counselors found useful information here, and their shared interest inspired many fruitful conversations about the role of religion in healthy human development.

In recent years, however, these interpersonal, humanistic practices of therapy have been swept aside and replaced by the increasingly widespread use of psychoactive drugs. The mental health system, in the U.S. at least, has turned into an impersonal delivery service for prescription medications and short-term cognitive behavioral therapy. This bears little resemblance to the rich, intimately detailed clinical practices that for so many years were integral to the psychology of religion.

To be clear, many psychoactive drugs save lives and help people stabilize enough to benefit from other treatments. But the skyrocketing use of these medications has severely undermined the efforts of psychotherapists and pastoral counselors to practice their healing crafts. Unfortunately I see few people in CSR who regard this as a problem for the field.

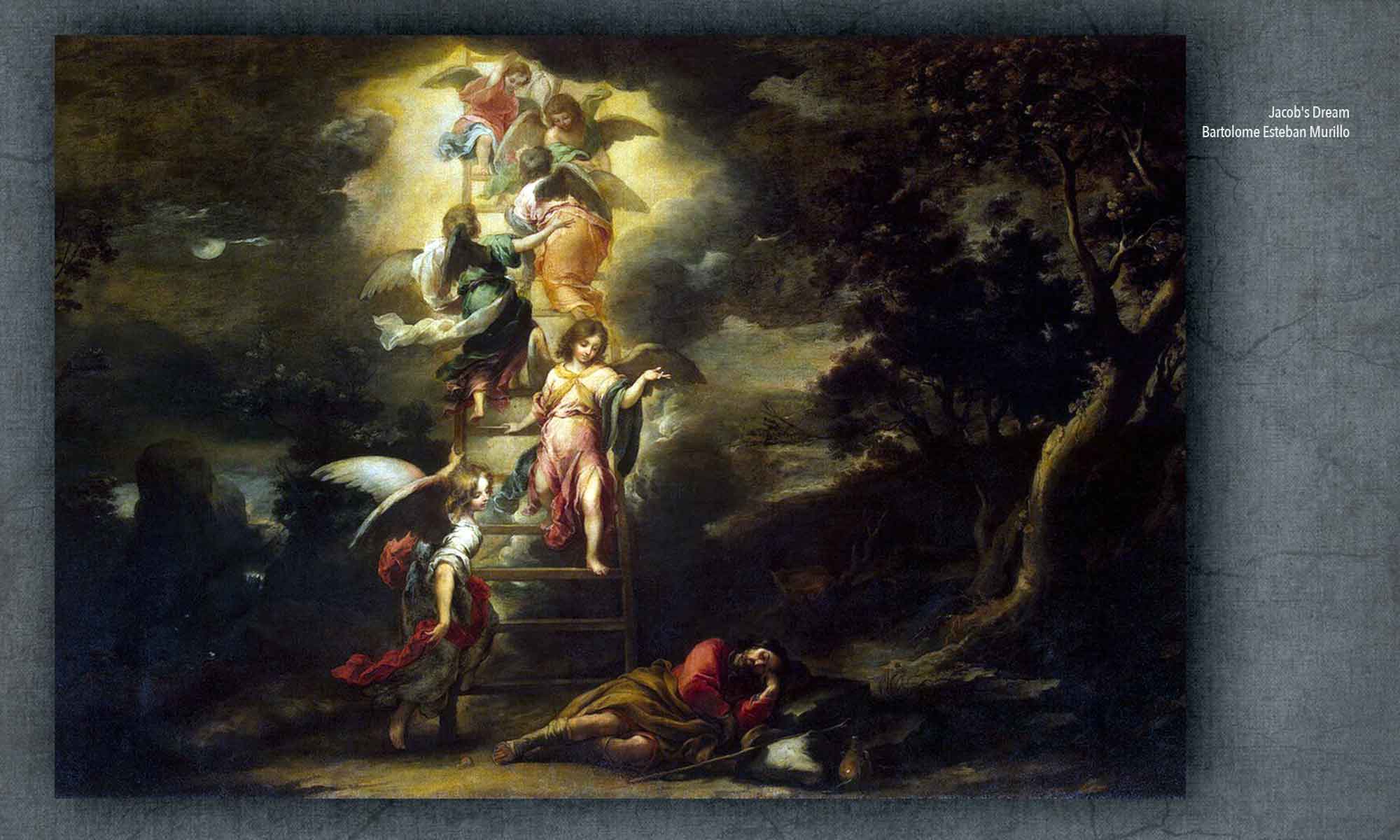

The third loss I want to mention regards an appreciation for the multiplicity of religious experiences, from mystical visions and dreams to possession, trance, and ecstasy. These phenomena are difficult to measure using brain scanning technology, and in any case such “altered states of consciousness” obviously deviate from the mind’s functioning in a normal waking condition—the state to which most psychoactive drugs and cognitive therapies are trying to return a person. Hence, CSR researchers have tended either to ignore mystical experiences or treat them as pathological failures of normal brain functioning, like bad pieces of neural code. The result is a shallow, homogenized view of human religiosity that excludes precisely those unusual, intensified experiences that William James said more than 100 years ago were key to a psychological understanding of religious life.

On this count we should be no less skeptical toward supposedly “pro-religion” researchers like Eugene D’Aquili and Andrew Newberg, whose brain imaging studies of people in meditation allegedly reveal a common neurological core of all mystical experiences (what they refer to as “absolute unitary being”). Their claim does not stand up to either empirical or conceptual scrutiny, and yet many people have accepted it because it seems to give a neuroscientific “seal of approval” to the study of mysticism. This to me is the worst of all worlds: taking poor practices from neuroscience and using them to dumb down the psychology of religion.

So, these three losses, of history, therapy, and mysticism—that’s the bad news of recent years. But there is good news, too. For instance, a new branch of research, known as social neuroscience, is taking more seriously the idea that we cannot just study brains, we have to study brains in bodies that live within families, who live within broader social and cultural contexts. It turns out that normal, healthy brain development depends fundamentally on a supportive social environment, on a lively stream of interpersonal relationships. I know that in the last years of his life Don Browning, who taught religion and psychological studies here at the Divinity School, was having conversations with social neuroscientists in the University, and he engaged with them as Paul Ricoeur might have done, seeking new prospects for a mixed discourse. Following Browning’s example, I encourage the psychology of religion and CSR to pursue more engagement with this area of brain research.

Still, even the good news has an asterisk attached. I’ve begun wondering if the appearance of social neuroscience is actually a sign that the brain boom has peaked. There seems to be a kind of self-deconstructing process at work here. If we cannot understand the brain without looking beyond the brain, then neuroscience loses its status as an ultimate source of explanatory authority.

The future of the psychology of religion will not, I venture to say, center on brain research, or for that matter on genetics, or evolutionary biology, or the latest findings from any other scientific discipline. Rather, the future will depend—and I’m sorry, this isn’t going to sound very exciting, but I think it’s true—on data management, meaning our ability to gather, sort, analyze, and creatively integrate information from many different sources. The Decade of the Brain is over, but the Century of Big Data is just beginning.

I don’t know about each of your different areas of specialization, but in mine the “Moneyball” changes are happening very fast, with torrential volumes of new information and the emergence of amazingly powerful tools of analysis. In 2009, motivated in large part by a fear of being left behind, I began developing the Sleep and Dream Database, an online digital archive and search engine for empirical dream research. (With the help, I should say, of software engineer Kurt Bollacker, U.C. Santa Cruz psychologist Bill Domhoff, and his coding colleague Adam Schneider.) At this point the database includes more than 15,000 dream reports from a variety of sources, including demographic surveys, personal journals, psychology experiments, and historical records.

There are many different analytic paths a psychologist of religion could follow using these materials. [All of the following examples have links to sample data in the SDDb.]

For example, one could sort through all the dream reports in the SDDb with words relating to religion.

Or, one could look at just the dream reports of people who identify themselves as Born-Again Christians.

Or one could compare the dream recall frequencies of people (American adults) who do or do not consider themselves more “spiritual than religious.”

I mention the SDDb because it is a small but practical example of how to make adaptive use of big data technologies rather than becoming overwhelmed by them. Of course, there are many limits to this kind of quantitative analysis of what Freud would call “manifest” dream content, along with many questions about personal privacy, interpretive authority, and data security. But I would like to close my presentation by at least gesturing beyond the critique of neuro-nonsense, and offering the hint of a more constructive response to the question that has drawn all of us here, namely how to promote a more prosperous future in the psychological study of religion.

Thank you.

I want the OA to be real. I think maybe it actually is real.

I want the OA to be real. I think maybe it actually is real.