I’ve just finished writing a new book about a young woman in 16th century Spain whose uncannily accurate prophetic dreams led to her arrest and torture by the Inquisition. The book is titled Lucrecia the Dreamer: Prophecy, Cognitive Science, and the Spanish Inquisition, to be published by Stanford University Press in early 2018. Lucrecia’s case is by far the most dramatic and compelling historical example of prophetic dreaming I have ever encountered. Truth is indeed stranger than fiction.

Below is an excerpt from the first page of the Introduction.

This is the story of a young woman who was violently persecuted because of her dreams. The fact that she dreamed frequently and vividly from an early age does not make her especially unusual since every society, from ancient times to the present day, has its share of such gifted people. What makes her story remarkable and historically significant is that she focused her dreaming abilities on gaining insights into the most pressing dangers facing her country. She was born a big dreamer and then, with the help and guidance of various supporters, she amplified her oneiric powers to new levels of visionary intensity.

For that, she was condemned as a traitor and a heretic.

Her name was Lucrecia de Leon. Born in 1568 in Madrid, Spain, she was the oldest of five children raised in a family of modest economic means… As her parents and neighbors later testified, Lucrecia was an active dreamer from early childhood. In the fall of 1587, when she was not quite 19, she mentioned one of her odd dreams to a family friend visiting her house. This friend later described the dream to a nobleman, Don Alonso de Mendoza, who was known to be deeply interested in mystical theology and apocalyptic omens. Curious to hear more, Don Alonso arranged to record Lucrecia’s dreams on a daily basis. For the next three years he collected her dreams, analyzed them in relation to passages in the Bible, and showed them to other people concerned about the future of Spain. Public interest in Lucrecia’s dreams grew, and so did the disapproval of church authorities whose job it was to guard against political dissent and unorthodox spirituality. In 1590 King Phillip ordered the Inquisition to arrest Lucrecia. Now 21 years old and several months pregnant, she was brought to the Inquisition’s secret prison in the nearby city of Toledo and tried for heresy and treason. The carefully recorded collection of her dreams became a primary source of evidence against her.

The first part of the book tells the story of Lucrecia’s life and dreaming and her upbringing as an illiterate but very pious Catholic young woman in the capital city of the most powerful empire in the world at that time. The second part of the book focuses on her dream reports, which the Inquisition tried for five years to compel her to admit were fraudulent fabrications. I make the case that the findings of modern cognitive science indicate Lucrecia was not lying but was telling the truth–she was honestly describing genuine dreams that accurately anticipated dangers to her country, specifically the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. If I could use a time machine to travel back four centuries to the Inquisition’s court in Toledo, this is the expert testimony I would offer based on my analysis of the evidence of her dream reports.

I only wish the book were coming out sooner! Actually, for a university press, the manuscript is racing through the production process, and I’m grateful for the care and attention of the editorial staff. The text will be the first entry in a new series, “Spiritual Phenomena,” aimed primarily at academic audiences but also appealing to general readers interested in the creative interplay of mind, body, spirit, and culture. I certainly wrote Lucrecia the Dreamer with the goal of making her story accessible to readers from all backgrounds. The historical evidence of her extraordinary capacities for future-oriented dreaming has implications far beyond the relatively narrow concerns of academics. Her story highlights the existence of latent powers of the human imagination that have tremendous relevance today, during another era of unstable leadership and looming dangers for the reigning global empire.

Notes:

The first image is a funnel used by the Inquisition to torture prisoners by means of the “toca,” essentially a form of waterboarding. I took the picture at the Museum of Torture (yes there is such a place) in Toledo.

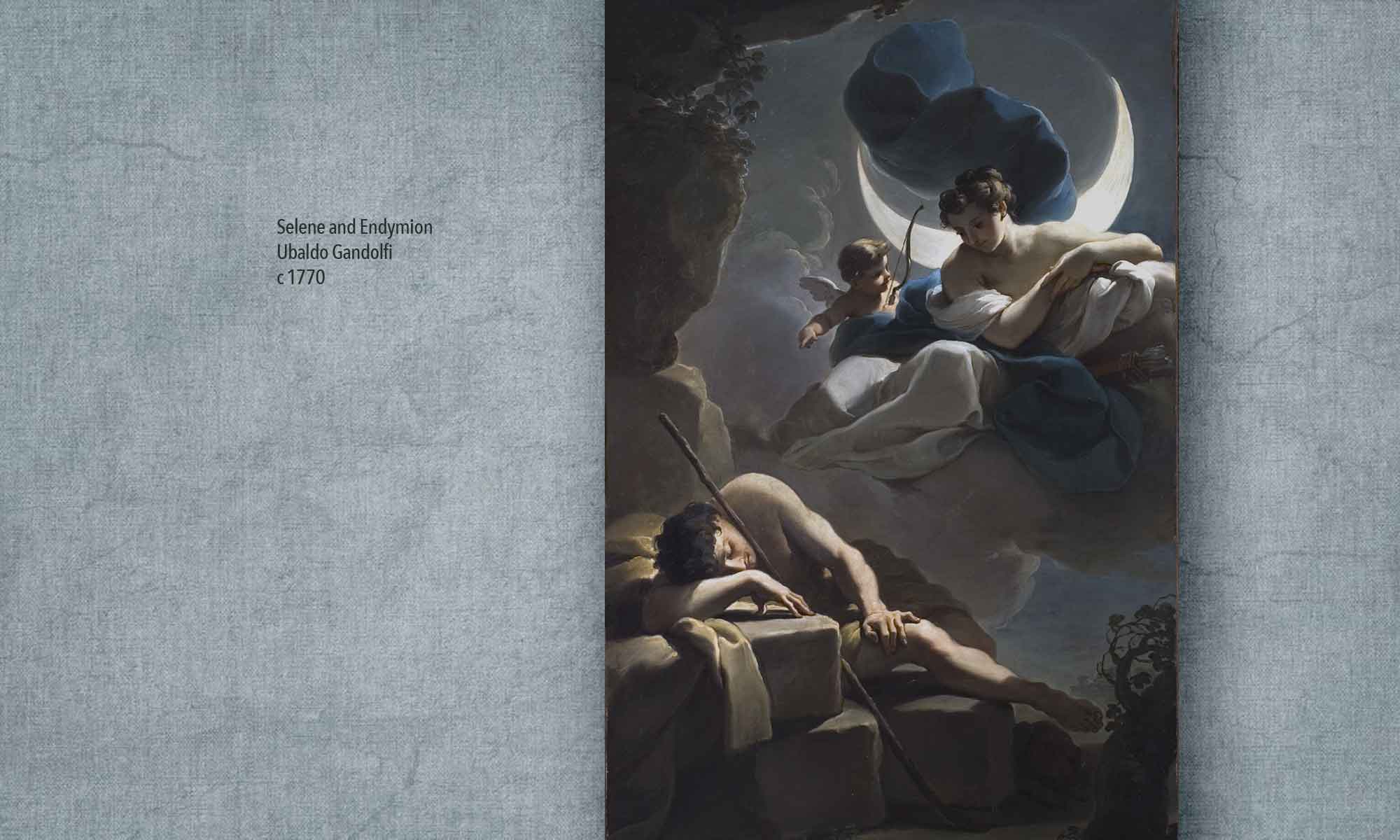

The second image will be the basis of the book’s cover. It’s a painting my wife and I bought in Amsterdam many years ago, and I’ve always felt it echoes something of Lucrecia’s story (no direct image of her remains).

Re the word “oneiric,” a friend who read a draft of the manuscript questioned whether I really need to use this term in the first paragraph. Here’s the hopefully clarifying endnote I added to the text at the end of the offending sentence: “The English word dream comes from a Proto-Germanic word, draugmaz, which meant dream, deception, delusion, hallucination, festivity, and ghost. The Greek word oneiros comes from oner in Proto-Indo-European (the oldest known human language), meaning both dreams and the figures who appear in them. The Spanish word sueño derives, like somnium in Latin and songe in French, from another Proto-Indo-European word, swepno, meaning sleep.”