The value of keeping a dream journal is inherent in the practice itself. Simply recording your dreams on a regular basis will increase your dream recall, deepen your self-knowledge, and help you maintain emotional balance in waking life. You can enjoy these benefits even if you never look back at your journal after recording each dream.

The value of keeping a dream journal is inherent in the practice itself. Simply recording your dreams on a regular basis will increase your dream recall, deepen your self-knowledge, and help you maintain emotional balance in waking life. You can enjoy these benefits even if you never look back at your journal after recording each dream.

But if you do have the opportunity to look back and review your journal over a period of time, you can learn some amazing things about yourself and the world in which you live.

I’ve been keeping a dream journal for more than 30 years, and the discoveries never stop coming. I study my journal both for personal insight and for new ideas to explore in my research with other people’s dreams. At the end of each calendar year I go back over the last 12 months of my dreams to explore the recurrent patterns and themes, using the word search tools of the Sleep and Dream Database (SDDb) to make an initial survey. This year’s review provides an incredibly accurate portrait of my concerns and interests in waking life, and gives me lots of inspiration for new research to pursue.

The results of the initial word search analysis are presented in the table in the previous post. I compared the results of my 2018 dreams with my dreams from 2016 and 2017. I also compared them with the male and female “baselines.” The baselines are two large collections of dreams gathered by various researchers to provide a source of “normal” dreaming in the general population. (I describe the baselines in more detail in my Big Dreams book.)

To analyze these dreams I used the SDDb 2.0 template of 40 word categories in 8 classes, listed in the lefthand column. The percentages to the right of each category indicate how often a dream in the given set includes at least one reference to a word in that category.

In 2018 I remembered one dream each night, as I did in 2016 and 2017. The average length of the dreams increased during this time (102 in 2016, 111 in 2017, 116 in 2018). This suggests the word search results will tend to be a little higher in the 2018 set, just because there are more total words to search. This will also be true in comparisons with the baseline dreams, which have an average length of 100 words (females) and 105 words (males).

Keeping that in mind, the 2018 dreams had more references to vision and color than previous years, while other sensory perceptions (hearing, touch, smell & taste) stayed the same. The table doesn’t show it, but the most frequently mentioned colors in my 2018 dreams were white, black, green, gray, and blue. For both of these categories (vision and color), my dreams have many more references than either the male or female baselines.

The emotion references in the 2018 dreams are pretty similar to 2016 and 2017. I have much more wonder/confusion than the male and female baselines, and somewhat more happiness.

The 2018 dreams have a rise in references to family characters, and to females generally. The frequencies of references to animals, fantastic beings, and males are quite steady from 2016 to 2018. Compared to the baselines, my family references are still rather low, my animal references are high, and my female references are very high.

The three categories of social interaction—friendliness, physical aggression, and sexuality—are all steady from 2016 to 2018. The sexuality frequencies are somewhat higher than the baselines.

The frequencies of my 2016-2018 dreams and the baselines are all similar on the categories of walking/running, flying, and falling. My dreams have fewer references to death than the baselines.

The cognitive categories—thinking, speech, reading & writing—are consistent across 2016-2018, with higher frequencies of thinking than the baselines.

The cultural categories are also remarkably consistent from 2016 to 2018, with a slight rise in references to food & drink and art. Compared to the baselines, my dreams have fewer references to school and more to art.

Of the four elements, the frequencies of fire and air are consistent in my 2016-2018 dreams and the baselines. My dreams have more references to water and earth.

This kind of analysis is quite superficial, of course. It ignores personal associations, narrative flow, and all the subtle qualities of dreaming that can’t be captured in numbers. That’s true, and yet it’s also true that a well-crafted word search analysis can reveal some fascinating themes that are both accurate and thought-provoking.

One of the most striking results of this initial analysis is the remarkable consistency over time of most of the word categories. There are a few significant changes, which I’ll discuss in a moment. But those changes are more dramatic when set in the bigger context of strong consistency across word categories as diverse as air (3% in 2016, 4% in 2017, and 4% in 2018), touch (12, 11, 13), anger (7, 8, 8), fantastic beings (4, 4, 3), physical aggression (16, 17, 17), flying (7, 6, 7), and clothing (18, 19, 21). As wild and unpredictable as individual dreams may be, in the aggregate they seem to follow steady long-term patterns.

Against that background of consistency, the changes that do occur over time are all the more intriguing.

The rise in references to vision and color from 2016 to 2018 seems related to the lengthening of my dream reports over this time. As my reports get longer, I apparently need to use more vision and color words to describe what happens in each dream.

The rise in references to family characters might be a return to a more “normal” ratio of family in my dreams. The family frequencies in 2016 and 2017 are actually the lowest I’ve ever had (extending the comparison back to 2010), so 2018 may be a bounce-back year. This would make sense in relation to my waking life: 2016 was the beginning of the “empty nest,” when the last of our children moved out of the house.

The rise in references to female characters is the most intriguing. The references to male characters stayed mostly the same from 2016 to 2018 (47, 44, 43), so the 2018 increase in female references leads to a big gender gap (59% female vs. 43 male). The baselines actually have slightly higher frequencies of male references vs. female references, so the variation in my 2018 dreams is even more unusual.

What might account for this change? My first thought is political. American society, as I currently perceive it, is dominated by destructive masculine energies, and change is only going to come once we bring more women to positions of power. I’m trying harder than ever in waking life to listen to female voices, and that intention may have influenced the patterns of my dreaming.

Two other features of the analysis pique my curiosity.

One is the rise of references to art over 2016-2018 (7, 14, 15), which I believe correlates with my increased participation as a board member of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. I wonder if other people who become more involved with an artistic group or practice also experience a rise in their dreams about art. I also wonder if my rise in art references might be connected to my higher frequencies of vision and color.

The other feature I’d like to explore further is the consistently low frequency of references to religion during all three years (3, 4, 3). This might seem odd since I have two graduate degrees in religious studies, and I’ve written several books about religion. But at the same time I never attend church, and I don’t belong to any religious group or denomination. My dreams seem to reflect the latter reality, my personal behavior rather than my scholarly pursuits.

In a recent survey that I’ve been analyzing with the help of Michael Schredl, we asked people to choose one of the following categories to describe their religious identity—Protestant, Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Mormon, Agnostic, Atheist, Nothing in Particular, and Something Else. I would definitely categorize myself as “something else”—not one of the religious identities, but not one of the non-religious identities, either. And it turns out (previewing the statistical findings Michael and I will soon publish) that people who identify religiously as “something else” have the highest interest in dreams compared to other groups. This makes me more curious than ever to understand the beliefs of people who religiously identify as “something else,” and how those beliefs relate to their attitudes towards dreaming.

I’m left with a final question, which will guide me in 2019: To what extent do these patterns reflect the past, and to what extent do they map the future?

####

This post first appeared in Psychology Today on February 5, 2019.

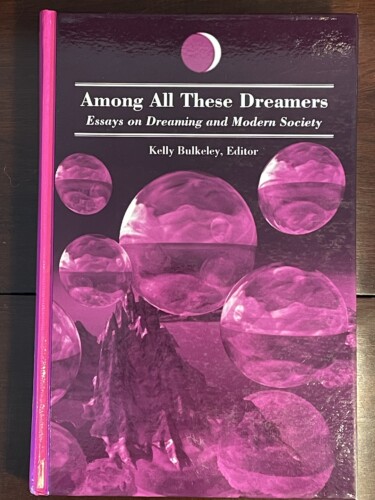

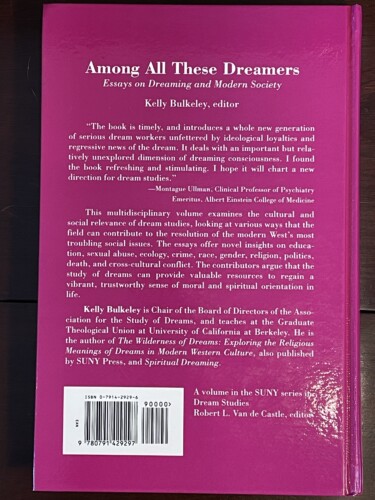

The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

An academic dissertation is written in compliance with a host of official requirements designed to focus the project and give it the best chance of successful completion. Those requirements definitely influenced how my dissertation and first book, The Wilderness of Dreams (1994), came to be what it is. As I sat down to write my second book, I remember a moment of almost dizzy uncertainty about taking the first steps forward. I knew even before finishing WD that I wanted to write a book about the religious and spiritual aspects of dreaming through history. The first chapter of my dissertation offered a survey of that material, but I had accumulated a larger store of references, much more than could be presented in a single chapter. A book-length study seemed worthwhile, but what exactly would it look like?

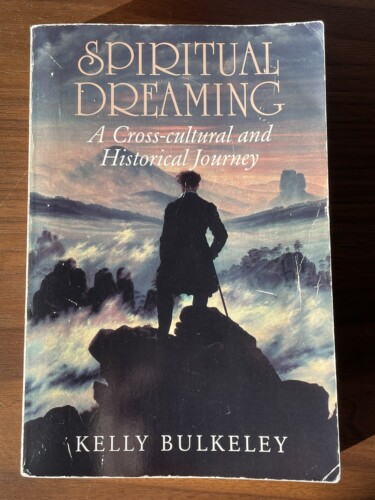

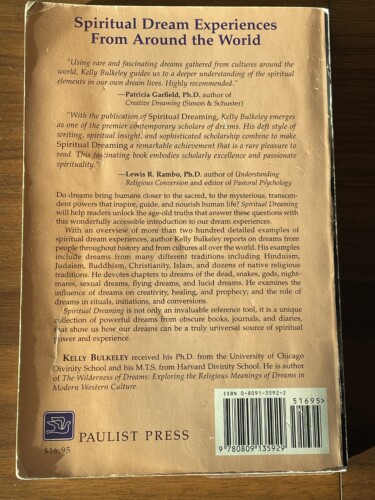

An academic dissertation is written in compliance with a host of official requirements designed to focus the project and give it the best chance of successful completion. Those requirements definitely influenced how my dissertation and first book, The Wilderness of Dreams (1994), came to be what it is. As I sat down to write my second book, I remember a moment of almost dizzy uncertainty about taking the first steps forward. I knew even before finishing WD that I wanted to write a book about the religious and spiritual aspects of dreaming through history. The first chapter of my dissertation offered a survey of that material, but I had accumulated a larger store of references, much more than could be presented in a single chapter. A book-length study seemed worthwhile, but what exactly would it look like? My friend and mentor Jeremy Taylor had published Dream Work (1983) with Paulist Press and spoke highly of their editor, Lawrence Boadt. That’s how I came to make an arrangement with Paulist to publish Spiritual Dreaming, with back-cover endorsements from Patricia Garfield and Lewis Rambo. Patricia was a co-founder of the IASD and author of several well-regarded books on dreams, and Lewis was a professor of religion and psychology at San Francisco Theological Seminary and my faculty sponsor at the Graduate Theological Union, where I had become a Visiting Scholar after leaving Chicago.

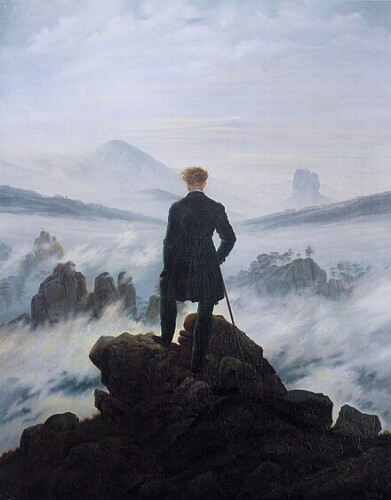

My friend and mentor Jeremy Taylor had published Dream Work (1983) with Paulist Press and spoke highly of their editor, Lawrence Boadt. That’s how I came to make an arrangement with Paulist to publish Spiritual Dreaming, with back-cover endorsements from Patricia Garfield and Lewis Rambo. Patricia was a co-founder of the IASD and author of several well-regarded books on dreams, and Lewis was a professor of religion and psychology at San Francisco Theological Seminary and my faculty sponsor at the Graduate Theological Union, where I had become a Visiting Scholar after leaving Chicago. The front cover is a painting from Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog (1818), a classic of early Romantic aesthetics, although I didn’t know that at the time—I just liked the way this image balanced the cover of WD, which was set deep inside a Redwood-lined creek; here with SD, we’re reaching the top of the ridge and discovering a big open view to enjoy.

The front cover is a painting from Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog (1818), a classic of early Romantic aesthetics, although I didn’t know that at the time—I just liked the way this image balanced the cover of WD, which was set deep inside a Redwood-lined creek; here with SD, we’re reaching the top of the ridge and discovering a big open view to enjoy. Here are the recent posts I have written for Psychology Today, going back to the middle of last summer. Although each one is written as a stand-alone discussion of a special topic in dreaming, I now realize they also form a series of interrelated texts, like the chapters of a book I didn’t consciously know I was writing….

Here are the recent posts I have written for Psychology Today, going back to the middle of last summer. Although each one is written as a stand-alone discussion of a special topic in dreaming, I now realize they also form a series of interrelated texts, like the chapters of a book I didn’t consciously know I was writing…. Despite the many crises afflicting the world right now, or perhaps because of them, my Muses have been quite active recently. Urgent, even. They have inspired several writing projects I hope to share soon.

Despite the many crises afflicting the world right now, or perhaps because of them, my Muses have been quite active recently. Urgent, even. They have inspired several writing projects I hope to share soon.  Escape from Mercury – a science-fiction novel, co-edited with T.A. Reilly, in production with a private publisher, to be released on 1/1/22 at 13:00 ICT. The novel portrays an alternate history in which NASA launches a manned mission to the planet Mercury on December 3, 1979, using Apollo-era rocketry that was specifically designed for post-Lunar flights. In the present “real” timeline, those plans were abandoned. The novel reimagines the US space program continuing onward and aggressively pushing beyond the Moon, and suddenly discovering dimensions of our interplanetary neighborhood unforeseen by any but the darkest of Catholic demonologists. “The Exorcist in Space” is the tagline.

Escape from Mercury – a science-fiction novel, co-edited with T.A. Reilly, in production with a private publisher, to be released on 1/1/22 at 13:00 ICT. The novel portrays an alternate history in which NASA launches a manned mission to the planet Mercury on December 3, 1979, using Apollo-era rocketry that was specifically designed for post-Lunar flights. In the present “real” timeline, those plans were abandoned. The novel reimagines the US space program continuing onward and aggressively pushing beyond the Moon, and suddenly discovering dimensions of our interplanetary neighborhood unforeseen by any but the darkest of Catholic demonologists. “The Exorcist in Space” is the tagline. 2020 Dreams – a digital project co-authored with Maja Gutman, under contract with Stanford University Press as part of their new Digital Projects Program. We are looking at a large collection of dreams that people experienced during the year 2020, and using a variety of cutting-edge tools of data analysis and visualization to highlight patterns in the dreams and their meaningful connections to major upheavals in collective life–the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental disasters, protests for social justice, and the US Presidential election. We have just reached an agreement with the Associated Press (AP) to use their news data from 2020 as our waking-world comparison set. Our hope is to expand on the findings of Charlotte Beradt and others who have shown how dreams can reflect the impact of collective realities on individual dreams, thus providing a potentially powerful tool of social and cultural analysis.

2020 Dreams – a digital project co-authored with Maja Gutman, under contract with Stanford University Press as part of their new Digital Projects Program. We are looking at a large collection of dreams that people experienced during the year 2020, and using a variety of cutting-edge tools of data analysis and visualization to highlight patterns in the dreams and their meaningful connections to major upheavals in collective life–the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental disasters, protests for social justice, and the US Presidential election. We have just reached an agreement with the Associated Press (AP) to use their news data from 2020 as our waking-world comparison set. Our hope is to expand on the findings of Charlotte Beradt and others who have shown how dreams can reflect the impact of collective realities on individual dreams, thus providing a potentially powerful tool of social and cultural analysis. The Scribes of Sleep: Insights from People Who Keep Dream Journals – a non-fiction book in psychology and religious studies. Currently being written, under contract with Oxford University Press, likely publication in early 2023. This book brings together many sources of research about people who record their dreams over time, and what they learn from the practice. Seven historical figures are the primary case studies in the book: Aelius Aristides, Myoe Shonin, Lucrecia de Leon, Emanuel Swedenborg, Benjamin Bannecker, Anna Bonus Kingsford, and Wolfgang Pauli. A close look at their lives, their dreams, and their creative works (religiously, artistically, scientifically) suggests that keeping a dream journal seems to appeal to people with a certain kind of spiritual attitude towards the world. The stronger argument is that keeping a dream journal actively cultivates such an attitude….

The Scribes of Sleep: Insights from People Who Keep Dream Journals – a non-fiction book in psychology and religious studies. Currently being written, under contract with Oxford University Press, likely publication in early 2023. This book brings together many sources of research about people who record their dreams over time, and what they learn from the practice. Seven historical figures are the primary case studies in the book: Aelius Aristides, Myoe Shonin, Lucrecia de Leon, Emanuel Swedenborg, Benjamin Bannecker, Anna Bonus Kingsford, and Wolfgang Pauli. A close look at their lives, their dreams, and their creative works (religiously, artistically, scientifically) suggests that keeping a dream journal seems to appeal to people with a certain kind of spiritual attitude towards the world. The stronger argument is that keeping a dream journal actively cultivates such an attitude…. Here Comes This Dreamer: Practices for Cultivating the Spiritual Potentials of Dreaming – a non-fiction book addressed to general readers interested in deeper explorations of their dreaming. Currently being written, under contract with Broadleaf Books, likely publication in the latter part of 2023. The challenge here, both daunting and exciting, is explaining the best findings from current dream research in terms that “curious seekers” will find meaningful and personally relevant. The book will have three main sections: 1) Practices of a Dreamer, 2) Embodied Life, and 3) Higher Aspirations. The title of the book signals a key concern I want to highlight: to be a big dreamer, like Joseph in the Bible (Gen. 37:19), can be amazing and wonderful, but it can also be perceived by others as threatening and dangerous. Sad to say, the world does not always appreciate the visionary insights of people who naturally have vivid/frequent/transpersonal dreams. I want to share what I hope are helpful and reassuring ideas about how to stay true to your innate dreaming powers while living in a complex social world where many people are actively hostile to the non-rational parts of the mind.

Here Comes This Dreamer: Practices for Cultivating the Spiritual Potentials of Dreaming – a non-fiction book addressed to general readers interested in deeper explorations of their dreaming. Currently being written, under contract with Broadleaf Books, likely publication in the latter part of 2023. The challenge here, both daunting and exciting, is explaining the best findings from current dream research in terms that “curious seekers” will find meaningful and personally relevant. The book will have three main sections: 1) Practices of a Dreamer, 2) Embodied Life, and 3) Higher Aspirations. The title of the book signals a key concern I want to highlight: to be a big dreamer, like Joseph in the Bible (Gen. 37:19), can be amazing and wonderful, but it can also be perceived by others as threatening and dangerous. Sad to say, the world does not always appreciate the visionary insights of people who naturally have vivid/frequent/transpersonal dreams. I want to share what I hope are helpful and reassuring ideas about how to stay true to your innate dreaming powers while living in a complex social world where many people are actively hostile to the non-rational parts of the mind.  People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.

People make many strange and unexpected discoveries when they begin exploring their dreams. Of these discoveries, perhaps the most surprising is an uncanny encounter with images, themes, and energies that can best be described as spiritual or religious. It’s one thing to realize you have selfish desires or aggressive instincts; it’s another thing entirely to become aware of your existence as a spiritual being. Yet that is where dreams seem to have an innate tendency to lead us—straight into the deepest questions of human life, questions we find at the heart of most of the world’s religious traditions.

The value of keeping a dream journal is inherent in the practice itself. Simply recording your dreams on a regular basis will increase your dream recall, deepen your self-knowledge, and help you maintain emotional balance in waking life. You can enjoy these benefits even if you never look back at your journal after recording each dream.

The value of keeping a dream journal is inherent in the practice itself. Simply recording your dreams on a regular basis will increase your dream recall, deepen your self-knowledge, and help you maintain emotional balance in waking life. You can enjoy these benefits even if you never look back at your journal after recording each dream.