Pro basketball players and coaches suffer chronic sleep deprivation. Can they find help in their dreams?

Pro basketball players and coaches suffer chronic sleep deprivation. Can they find help in their dreams?

On January 8, 1964, a 17-year old high school student named Randy Gardner set the world’s record for continual wakefulness: 264 hours, more than eleven straight days without sleep. Gardner was helped in his effort by Dr. William Dement, a pioneer of sleep medicine who stayed with him round-the-clock to help him achieve his goal. The worst times came during the wee hours of the night, when Gardner’s resolve faltered, but Dement said they found a sure-fire way to keep sleep at bay:

“Fortunately, playing basketball always worked. We almost had to drag him out to the backyard, but once he was there and got moving, he was much better.”

This little anecdote from the early history of sleep research illuminates a problem at the heart of the modern National Basketball Association. Professional basketball players are virtually guaranteed to suffer chronic sleep deprivation. For months on end they stay up late into the night and engage in intense, highly stressful physical competitions held in brightly lit, hyper-stimulating arenas full of thousands of screaming people. They must endure a constantly changing schedule of long-distance travel, shifting time zones, and unfamiliar food and lodging. It would be hard to intentionally design a system more likely to disrupt the natural, healthy rhythms of sleep.

Fortunately, a new awareness of the importance of sleep is growing among the players, coaches, and even the league schedulers. Two of the league’s premier players, Lebron James and Kevin Durant, have made their views on the subject clear:

James: “Sleep is the most important thing when it comes to recovery. And it’s very tough with our schedule. Our schedule keeps us up late at night, and most of the time it wakes us up early in the morning. … There’s no better recovery than sleep.”

Durant: “Of course, on the basketball side, you have to fine tune your skills. But on the other side, you have to fine tune your body. There’s a lot of remedies you can use as a basketball player to get better, but the easiest thing you can do is go to sleep.”

Much of the credit for the recent burst of attention to sleep and basketball goes to Dr. Cheri Mah, whose 2011 study of the Stanford University men’s basketball team found that increased sleep led to measurably better shooting, faster sprinting, and a higher sense of physical and mental well-being. Mah’s findings have inspired men’s and women’s teams at all levels to take sleep more seriously as an integral factor in overall player health and performance.

Mah’s research has also spawned a method of predicting the winners of NBA games with alarmingly high accuracy. ESPN writer Baxter Holmes has worked with Mah to devise a formula for evaluating how tired one team would be compared to another team on the night of a game against each other, especially on the second night of a back-to-back game. Their formula takes many factors into account:

Whether the game is home or away, the time elapsed between tip-offs (including hours lost from flying east), how rested the opponent is from play or travel and whether it’s part of a longer run of four games in five nights, or five games in seven.

As Holmes reports, the formula has a success rate of about 75% in predicting the winner of a game when one team is likely to be very sleep deprived and the other team is likely to be very well-rested. These predictions are made regardless of the team’s won/lost records, which is even more impressive in terms of identifying the direct competitive impact of healthy sleep. If this formula were revised to include the won/lost records, it’s easy to imagine the success rate of the sleep-driven predictions rising to nearly 100%.

This season has also highlighted the sleep challenges of coaches as well as the players. Two head coaches—Tyronn Lue of the Cleveland Cavaliers and Steve Clifford of the Charlotte Hornets—have been forced by health concerns to leave their teams for several weeks of recuperation. In both cases, doctors identified chronic insomnia as an important causal factor.

What can be done to help NBA players and coaches improve their sleep? The league is under growing pressure to eliminate back-to-back games, which would surely remove a major cause of disrupted sleep. But there’s only so much flexibility when trying to craft a season of 82 games for each of 30 teams in a time frame of 6 months. Even if back-to-backs are eliminated, the NBA’s regular season schedule will continue to put enormous pressure on everyone’s ability to get a healthy amount of sleep.

At this point, most teams have a sleep consultant of some kind, so players and coaches already have access to basic information about behavioral changes one can make for improving sleep. Unfortunately, knowing what you should do is not as easy as actually doing it. According to one coach quoted by David Aldridge at NBA.com,

“We’re all told what to do, but we don’t do it. We’re all told we have to eat healthy, we have to exercise and we have to get our sleep. All of us. Every coach. This is not like, ‘oh, wow, I never thought of that.’ But it’s hard to do it.”

What else is there? What other options exist for promoting better sleep, besides the standard methods of appealing to guilt and fear, focusing on behavioral markers, and relying on external authorities?

There is another approach, one that works well for some people and might work very well for NBA players and coaches. This approach draws on a new source of motivation for getting as much good sleep as possible: Better sleep is important because it leads to better dreaming.

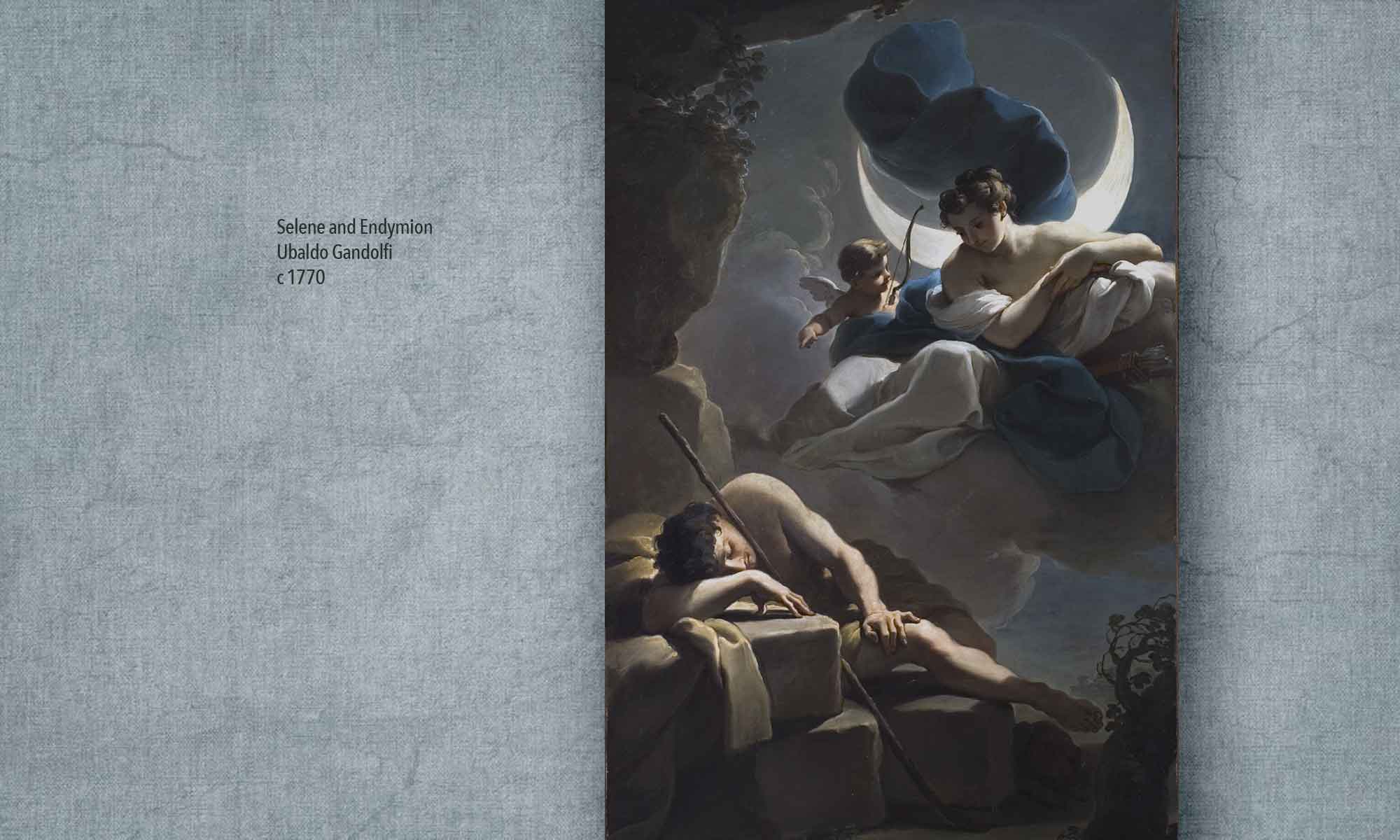

When you sleep, your mind does not simply shut down. Rather, it enters a different mode of functioning, a mode that can be described as a kind of play. Liberated from the constraints of the external world, your sleeping mind is free to imagine, explore, and experiment. Sometimes, during the phase known as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which occurs four or five times a night for most people, your brain becomes intensely activated, as much as when you are wide awake. These complex bursts of neural activation are an automatic, hard-wired feature of your sleep cycle, and they stimulate the psychological process of dreaming.

But why should anyone, let alone those who play or coach professional basketball, care about dreams? There are at least three reasons.

First, even if you never remember any of your dreams, the process of dreaming still contributes to your mental welfare in waking life. Researchers have found that dreaming promotes more efficient learning, memory formation, and the emotional integration of new experiences. The “bizarre” aspects of dreaming—strange settings, odd characters, impossible events—can be understood as playfully stretching your mind’s abilities, with the beneficial effect of increasing your mental flexibility and improving your readiness to deal with unexpected situations in waking life. In this way, dreaming is like mental yoga. It loosens the rigid boundaries of your waking ego, expands the range of your imagination, and keeps your mind open and alert to new possibilities.

This means that sleep is especially important for basketball players and coaches who are continuously trying to optimize their performance, because if they sleep well, their dreams will naturally boost their mental health and adaptive flexibility, whether or not they consciously remember any of them.

Second, chances are you that do remember at least a few of your dreams. If you pay even a little attention to them, you’ll notice they often revolve around your current emotional concerns. Whatever preoccupies you in waking life—whatever you care most about—is very likely to show up in your dreams. In this way, dreams offer a surprisingly honest mirror of how you’re feeling about the most important people, challenges, and conflicts in your waking life. Every dream you remember is an opportunity to expand your self-awareness and strive for greater emotional balance.

For pro basketball players, good sleep can open the door to a valuable source of fresh information about how they’re playing, how their bodies are responding, and how they’re getting along with teammates, coaches, opponents, fans, and the media. Dreams are a powerful tool for identifying hidden fears and emotional obstacles that get in the way of peak athletic performance.

Third, if you actively engage with your dreams by writing them in a journal, several things will happen. Your recall will likely increase, as you become more consciously attuned to the rhythms of your sleeping mind. Your sense of time will expand, as you understand more of your past and envision more of your future. You will notice the emergence of creative insights and innovative ideas that offer new ways of problem-solving in waking life. Eventually, your dreams will begin changing as you psychologically “level up,” discovering new challenges and new opportunities for growth. You may become “lucid” or self-aware in some of your dreams, and able to interact more intentionally with the characters and settings. You can practice dream incubation, a method of formulating a question before sleep and then observing any subsequent dreams for possible responses to the question.

Looking at these potentials in a basketball context, good sleep combined with keeping a dream journal can set the stage for developing advanced forms of mental strength and clarity that will empower players to actualize their talents to the fullest. Dreaming can be a path towards deeper mindfulness, as Hindu and Buddhist meditators have known for many centuries. For NBA players and coaches, who need to keep their focus laser sharp despite constant distractions, a regular dialogue with their dreams can be a grounding practice that connects them with their core motivations and ultimate center of balance.

None of this is possible if the basic rhythms of one’s sleep cycle are badly out of sync. But once you start making an active effort to improve your sleep, you will also be improving the conditions for your dreams. And once you start actively exploring and cultivating the immense powers of your dreaming mind, the sky is the limit.

Note: this post was first published in Psychology Today, April 5, 2018.

Between January 8, 2015 and October 4, 2017, I remembered and recorded a dream every night for 1,001 consecutive nights. Now I’m studying the dreams and trying to find insights that can help in exploring the dream series of other people. I don’t expect anyone to accept my personal dreams as conclusive evidence for any general theory of human dreaming. Instead, I offer them as way of being transparent about the experiential grounding of my research pursuits. This is one of the ways I get ideas for new projects.

Between January 8, 2015 and October 4, 2017, I remembered and recorded a dream every night for 1,001 consecutive nights. Now I’m studying the dreams and trying to find insights that can help in exploring the dream series of other people. I don’t expect anyone to accept my personal dreams as conclusive evidence for any general theory of human dreaming. Instead, I offer them as way of being transparent about the experiential grounding of my research pursuits. This is one of the ways I get ideas for new projects. Most of these inferences—I’d say 11 of 13—are unmistakably accurate in identifying a continuity between a pattern of dream content and an aspect of my waking life concerns. The two I would question are numbers 10 and 12. Regarding the low frequency of dream references to school, I do in fact engage in a great deal of teaching and educational work, but it’s almost entirely online, and I rarely set foot inside a traditional school any more. Also, I no longer have school-age children living at home. So it seems my dreams are continuous with my physical behaviors relating to schools, but not with my computer-mediated educational activities.

Most of these inferences—I’d say 11 of 13—are unmistakably accurate in identifying a continuity between a pattern of dream content and an aspect of my waking life concerns. The two I would question are numbers 10 and 12. Regarding the low frequency of dream references to school, I do in fact engage in a great deal of teaching and educational work, but it’s almost entirely online, and I rarely set foot inside a traditional school any more. Also, I no longer have school-age children living at home. So it seems my dreams are continuous with my physical behaviors relating to schools, but not with my computer-mediated educational activities. Just added to the SDDb library is

Just added to the SDDb library is

All life on earth is fundamentally oriented toward the cyclical presence and absence of the sun. Every kind of living being has evolved internal clocks of approximately 24 hours in length that guide and regulate their biological processes and behaviors. These internal clocks are known as circadian rhythms, and they have long been observed as powerful factors in plant and animal life. But only recently have the details of how these clocks work become known, thanks to the work of this year’s trio of prize winners. Their studies, going back to the 1980’s, explain how circadian rhythms are programmed into the genetic activities of each cell at the molecular level.

All life on earth is fundamentally oriented toward the cyclical presence and absence of the sun. Every kind of living being has evolved internal clocks of approximately 24 hours in length that guide and regulate their biological processes and behaviors. These internal clocks are known as circadian rhythms, and they have long been observed as powerful factors in plant and animal life. But only recently have the details of how these clocks work become known, thanks to the work of this year’s trio of prize winners. Their studies, going back to the 1980’s, explain how circadian rhythms are programmed into the genetic activities of each cell at the molecular level. It may also give us new insights into the rhythms, cycles, and recurrent patterns in human dreaming. Anything that gives a new understanding of sleep has the potential to provide a new understanding of dreams, since dreaming naturally emerges out of the state of sleep. The ubiquity of dreaming in human experience throughout recorded history, in cultures all over the world, strongly suggests it is a phenomenon deeply rooted in our evolutionary heritage. It strengthens the argument in favor of this idea to show, as this year’s Nobel winners have done, that the circadian rhythms guiding our waking and sleeping behaviors are encoded in every cell in our bodies. There can no longer be any question that sleep is an absolutely vital feature of healthy human life. The study of dreams can build on this solid foundation in evolutionary biology to explore in more detail what exactly is happening in the mind and body during sleep that contributes so powerfully to human health.

It may also give us new insights into the rhythms, cycles, and recurrent patterns in human dreaming. Anything that gives a new understanding of sleep has the potential to provide a new understanding of dreams, since dreaming naturally emerges out of the state of sleep. The ubiquity of dreaming in human experience throughout recorded history, in cultures all over the world, strongly suggests it is a phenomenon deeply rooted in our evolutionary heritage. It strengthens the argument in favor of this idea to show, as this year’s Nobel winners have done, that the circadian rhythms guiding our waking and sleeping behaviors are encoded in every cell in our bodies. There can no longer be any question that sleep is an absolutely vital feature of healthy human life. The study of dreams can build on this solid foundation in evolutionary biology to explore in more detail what exactly is happening in the mind and body during sleep that contributes so powerfully to human health. In the next scene a supremely confident Master Ford brings a group of companions to his house to apprehend Falstaff. His wife, in the midst of sending out the dirty laundry, denies that Sir John is there. Master Ford contemplates the laundry basket, which is about to be sent out for “buck-washing” (a traditional means of laundering clothes by soaking and rinsing them repeatedly with lye, ash, or urine), and utters some strange lines: “Buck? I would I could wash myself of the buck! Buck, buck, buck! Ay, buck; I warrant you, buck—and of the season too, it shall appear” (III.iii.155-157).

In the next scene a supremely confident Master Ford brings a group of companions to his house to apprehend Falstaff. His wife, in the midst of sending out the dirty laundry, denies that Sir John is there. Master Ford contemplates the laundry basket, which is about to be sent out for “buck-washing” (a traditional means of laundering clothes by soaking and rinsing them repeatedly with lye, ash, or urine), and utters some strange lines: “Buck? I would I could wash myself of the buck! Buck, buck, buck! Ay, buck; I warrant you, buck—and of the season too, it shall appear” (III.iii.155-157). To be a king, one must give up sleep and dreams in favor of the ruling duties of waking life.

To be a king, one must give up sleep and dreams in favor of the ruling duties of waking life.