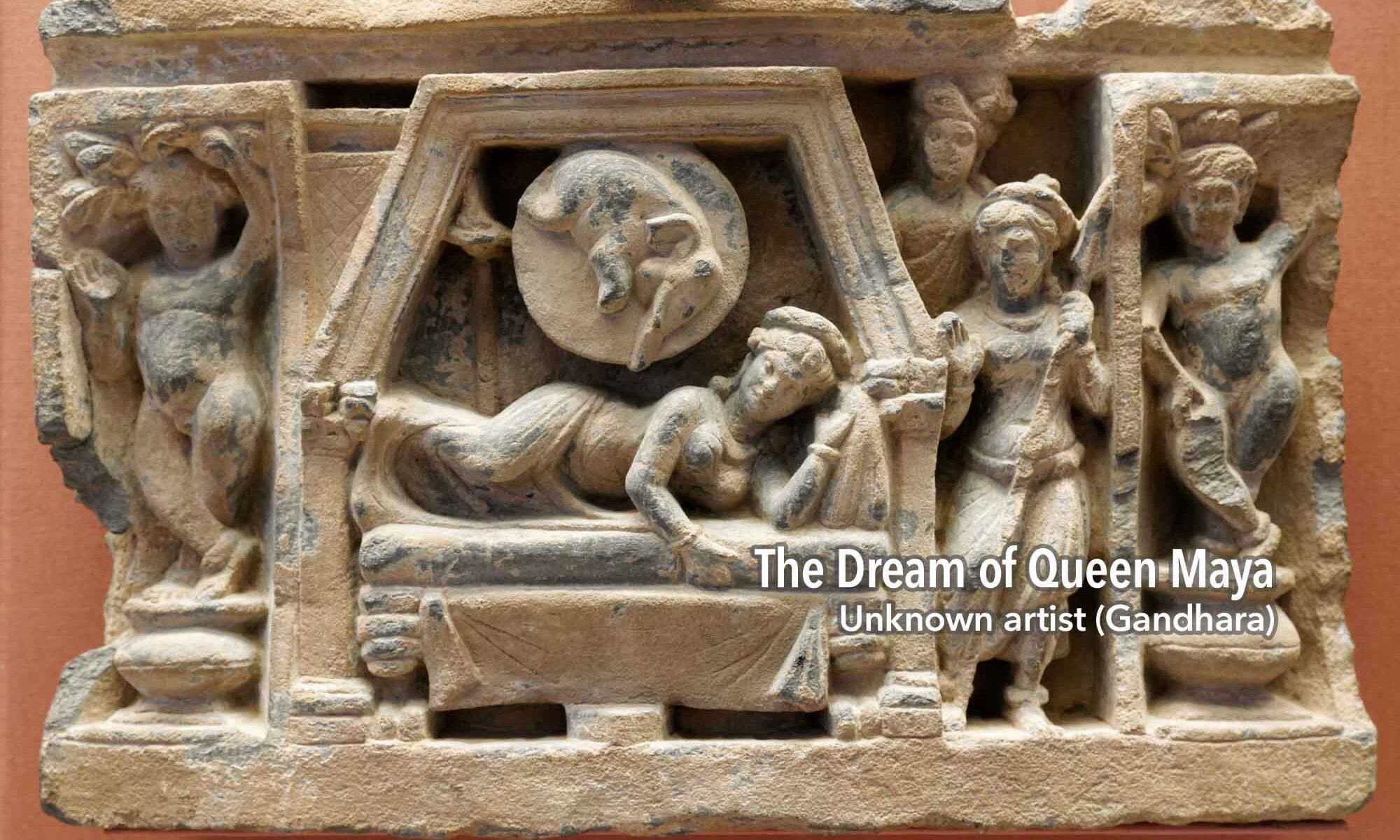

Sexual dreams have long been part of human experience, as we know from historical sources. For example, the Oneirocritica of Artemidorus, an ancient manual of dream interpretation, devoted several pages to the various types and classes of sexual dreams.

Sexual dreams have long been part of human experience, as we know from historical sources. For example, the Oneirocritica of Artemidorus, an ancient manual of dream interpretation, devoted several pages to the various types and classes of sexual dreams.

However, we do not know how widespread sexual dreams are, who has them most often, and when they begin.

In a survey I commissioned a couple of years ago, nearly 3000 American adults were asked the question, “Have you ever had a dream with sexual feelings or experiences?” Of those who answered “Yes,” a follow-up question was asked: “Did you have any sexual dreams before your first sexual activity in waking life?”

The answers to the first question were 69% Yes and 24% No for the men (1912 of them), and 58% Yes and 34% No for the women (1058 total), with 7% of the men and 8% of the women responding “Not Sure.”

On most other typical dreams questions (e.g., chasing, falling, visitation) the women answered Yes more often than did the men. Sexual dreams stood out as a significantly more frequent experience for the men.

For the follow-up question about sexual dreams before sexual activity, the gender disparity was even bigger: 48% of the men said Yes and 22% said No, whereas only 23% of the women said Yes while 39% said No.

Looking more closely at follow-up question results, the age of the participants mattered a lot. The frequency of Yes answers was much higher for younger than older people, although the gap between males and females remained for all ages.

| Males | Females | |||||

| Age | Yes | No | N/S | Yes | No | N/S |

| 18-29 | 76% | 8% | 15% | 55% | 22% | 22% |

| 30-49 | 55% | 16% | 29% | 31% | 37% | 32% |

| 50-64 | 44% | 24% | 33% | 17% | 39% | 44% |

| 65+ | 37% | 30% | 33% | 11% | 48% | 42% |

Other demographic variables (e.g., race, income, education, religion) did not correlate with any significant differences.

What can we learn from these results?

First, we have to consider the limitations of the data. Many people are simply reluctant to talk about sex. Dreams sometimes portray taboo, socially frowned upon sexual behaviors that people may not want to admit. Some religious traditions teach that sexual dreams should be shunned as demonic temptations. More generally, people vary in how well they can recall different types of dreams from earlier in life.

All these factors suggest the survey results are underestimating rather than overestimating the frequency of sexual dreams. Some of the participants probably answered “No” when the actual truth was “Yes,” while it’s unlikely that many participants said “Yes” when the accurate answer would have been “No.”

To explain these findings, we can appeal to both biology and culture. It makes sense that young people entering their prime years of reproductive potential would have dreams that anticipate and prepare them for this fundamental biological goal. Just as some nightmares simulate threats to our survival (e.g., being chased by wild animals) so we’re better prepared to face them in waking life, it could be that sexual dreams are simulating reproductive opportunities we will hopefully have in the future. Such dreams might have less biological value or significance for older people.

It could also be that young people in contemporary America are more likely to dream about sex because they are immersed in a culture filled with sexually arousing content. Dream content accurately reflects people’s biggest emotional concerns, and it’s plausible to assume that many young people today are thinking a lot about sex before they are sexually active. Again, such dreams would be less likely among older people whose emotional concerns no longer center on sexuality.

Both biological and cultural factors could also account for the gender differences. The process of sexual maturation may generate stronger physical pressures for young males than females, prompting a higher proportion of sexually explicit dreams. Cultural portrayals of sexuality certainly seem to emphasize male rather than female perspectives, which may stimulate relatively more dreaming about this subject.

These explanations are admittedly speculative and open to question. However, it is clear that dreaming is closely connected to our nature as sexual beings. Even before sexual activity in waking life we tend to be sexually active in our dreams, anticipating how it will happen, what it will feel like, and with whom we’ll share the experience. The fact that some dreams can lead to actual climax for both men and women suggests that dreaming is, at one level, a physiologically hard-wired means of preparing us for our lives as reproductive beings.