Dreaming, play, theater, science, religion, social and political crisis.

Dreaming, play, theater, science, religion, social and political crisis.

Jung, Freud, Shakespeare, a troupe of immigrant artists, Alice in Wonderland, Lucrecia de Leon, the US President.

These are the topics and the people I will be discussing most frequently in a series of presentations lining up for 2019. Each presentation will speak directly to the interests of a particular audience, and each one will also connect to the other talks I’m giving in ways that I hope will lead to a greater interwoven whole.

(All of these conferences and gatherings are still in the planning stages, so details may change.)

Society for Psychological Anthropology

Biennial Meeting, Santa Ana Pueblo, New Mexico

April 4-7

This will be part of a panel on “New Directions in the Anthropology and Psychology of Dreaming” organized by Robin Sheriff and Jeannette Mageo.

“Dreaming, Play, and Social Change”

This presentation offers a novel theory of dreaming—as a highly evolved form of play—and discusses its implications for new research in psychology and anthropology. The theory integrates findings from evolutionary biology, neuroscience, psychoanalysis, religious studies, and developmental psychology (especially D.W. Winnicott). This approach moves beyond the fruitless debates over the “bizarreness” of dreaming. From the play perspective, bizarreness in dreaming is a feature, not a bug. In dreams the mind is free to play, to explore, imagine, and envision new possibilities beyond the limits of conventional reality. Of special interest to anthropologists, the content of dreams, i.e., what people playfully dream about, mostly revolves around social life. Many of the cognitive abilities vital to waking sociality are also present in dreaming, which correlates with research showing that dream content accurately mirrors people’s most important waking relationships. In some instances, dreaming goes beyond mirroring the social world to actively striving to transform it; the playfulness intensifies, and the dreaming imagination labors to create something new, to go beyond what is to imagine what might be. This visionary potential is often activated during times of social conflict and crisis. Three brief examples will illustrate the playful dynamics of dreaming in relation to a crisis in the dreamer’s community: 1) the prophecies of Lucrecia de Leon, a young woman from 16th century Spain; 2) the creatively inspiring “big dreams” of a group of immigrant artists; and 3) the politically-themed dreams of present-day Americans about their current President.

For more information, click here.

International Association for the Study of Dreams

Regional Conference, Ashland, Oregon

May 31 to June 2

This is the general description of the event, which I am helping to host with Angel Morgan. On Saturday morning I will give a talk on the role of dreams in Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” and Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland,” both of which will be performed that weekend at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

“Theater, Dreams, and Art”

Shakespeare wrote “All the world’s a stage” and Carl Jung wrote that a dream is theater in which the dreamer is the scene, player, prompter, producer, author, public, and critic. The best plays are like the best dreams: surprising, decentering, mind-expanding, awe-inspiring, emotionally exhausting, and acutely memorable. They are unreal, yet realer than real; retreats into fantasy that catapult us into fresh engagement with the world. Many talented artists, as well as everyday creative people, have said they feel the same kind of freedom to explore their emotions in dreams that they do when they have an encounter with the artistic process. Many often connect the two by first logging their dreams, then drawing on the raw emotional content and imagery from their dream experiences to feed their art. That said, bridging dreams with theater and art tends to offer a wide variety of fascinating approaches. In this conference we hope to inform and inspire dreamers of all ages and backgrounds, as well as those who use theater, dreams, or art in their work, such as: parents, psychologists, therapists, counselors, writers, actors, directors, dancers, visual artists, and musicians.

For more information, click here.

International Association for the Study of Dreams

Annual Conference, Kerkrade, the Netherlands

June 20-26

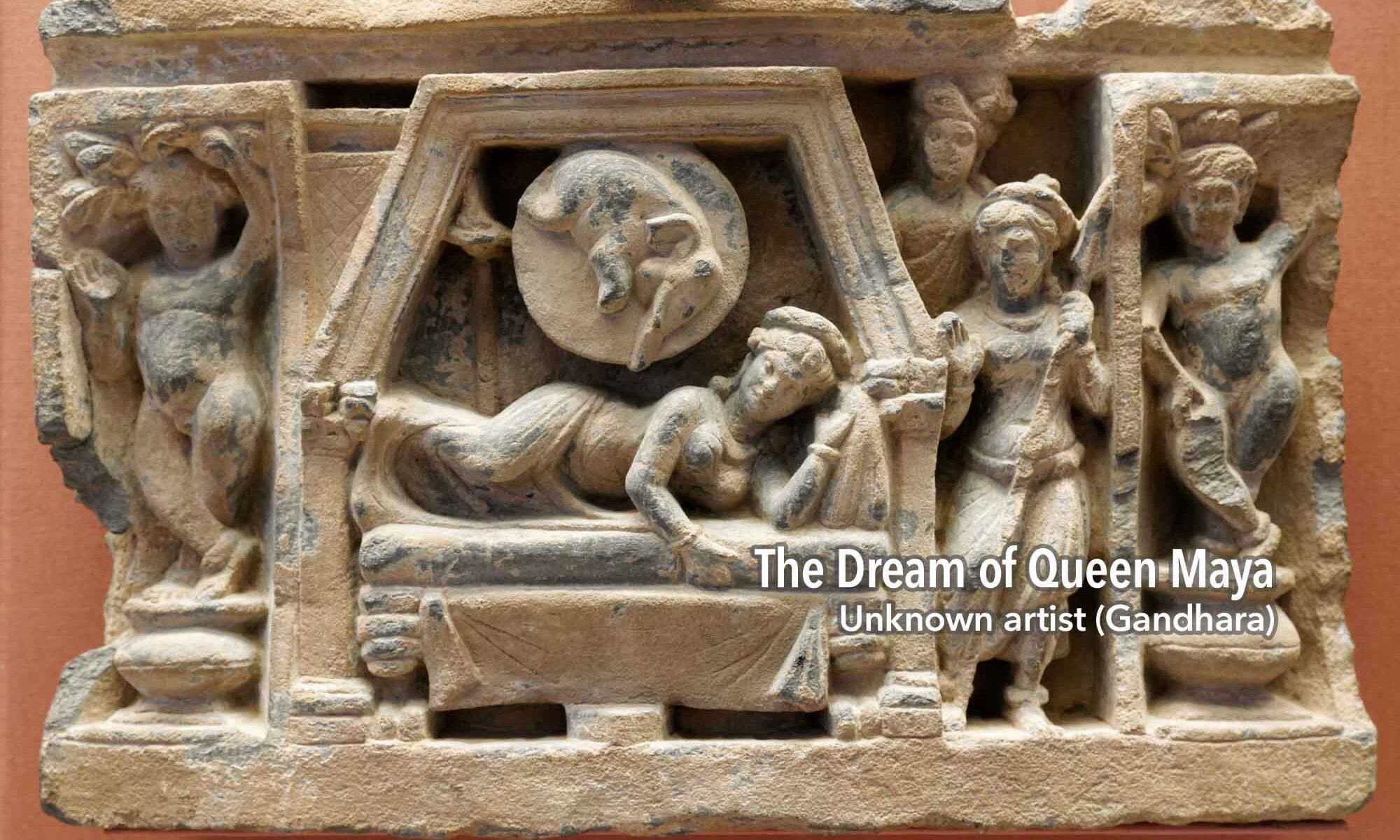

This is part of a panel I am organizing with Svitlana Kobets and Bernard Welt on “Visionary Dreams in Art, Religion, and History.”

“Vision and Prophecy in the Dreams of Lucrecia de Leon”

This presentation explores the visual imagery, religious symbolism, and prophetic warnings contained in the dreams of Lucrecia de Leon, a young woman from 16th century Madrid who was persecuted by the Spanish Inquisition as a traitor and heretic, despite the fact that many of her dream warnings came true.

This is part of a panel Jayne Gackenbach is organizing on the interplay of artistic practice and scientific inquiry.

“Dreaming Is Play: A Bridge Between Art and Science”

This presentation offers a theory that dreaming is a kind of play, the imaginative play of the mind during sleep. This theory has directly inspired me in new activities with art and artists: supporting regional theater, collaborating with the Dream Mapping Troupe, and cultivating a forested dream library.

For more information, click here.

American Academy of Religion

Annual Conference, San Diego, California

November 23-26

This is a “call for papers” topic that will soon be posted by the Cognitive Science of Religion (CSR) group of the American Academy of Religion, and open for submissions from all AAR members. If the CSR steering committee receives enough good proposals on this topic, there will be a panel session at the conference in San Diego with three or four presentations.

“Cognitive Science of Religion (CSR) Approaches to Dreaming”

The rise of psychology of religion in the early 20th century was driven in part by Freud’s and Jung’s efforts to understand the nature of dreams. What would a new 21st century approach to dreams look like, using the resources of CSR? Specifically, to what extent do cognitive functions known to operate in religious contexts (e.g., memory, imagination, metaphor, teleological reasoning, social intelligence, agency detection, dual-systems cognition) also operate in dreaming? To what extent does this shed new light on the various roles that dreams have played in the history of religions (e.g., theophany, healing, prophecy, moral guidance, visions of the afterlife)? Proposals are welcome that draw together detailed accounts of religiously significant dreaming with specific CSR concepts and theories.

For more information, click here.

New research highlights 13 areas of continuity between waking and dreaming.

New research highlights 13 areas of continuity between waking and dreaming. The Rev. Jeremy Taylor was one of the most prolific dream speakers and teachers of modern times. He traveled to every corner of the U.S., and to many countries around the world, reaching out to people and promoting greater awareness of dreaming. He combined his background as a Unitarian-Universalist minister with a deep familiarity with Jungian archetypal psychology to not only help people better understand their dreams, but to get them excited and energized about the amazing adventure of psychological growth and spiritual discovery that opens up once they start paying more attention to general human experience of dreaming.

The Rev. Jeremy Taylor was one of the most prolific dream speakers and teachers of modern times. He traveled to every corner of the U.S., and to many countries around the world, reaching out to people and promoting greater awareness of dreaming. He combined his background as a Unitarian-Universalist minister with a deep familiarity with Jungian archetypal psychology to not only help people better understand their dreams, but to get them excited and energized about the amazing adventure of psychological growth and spiritual discovery that opens up once they start paying more attention to general human experience of dreaming.

The latest series to be uploaded into the Sleep and Dream Database (

The latest series to be uploaded into the Sleep and Dream Database ( In the past couple of weeks I have spoken several times with journalists about

In the past couple of weeks I have spoken several times with journalists about