Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.

Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.

But…there was the secondary text issue. The change of mind and heart came when I recognized the creative opportunities in writing an overview of the history of modern dream psychology. As I looked at other versions of this history, and there were not many, I became increasingly confident that I could write a good, clear, multidisciplinary version of this story, whether or not it amounted to a secondary text. And then, once I got going, it was a very quick writing process. I’d say it took ten years of continuous study to be able to write the book in about three months.

As a way of orienting myself within the tremendous breadth and diversity of the field, and thus being able to explain its contours in clear terms to students new to this subject, I settled on three basic questions that I would ask at each new point in the story:

- How are dreams formed?

- What function or functions do dreams serve?

- Can dreams be interpreted?

These three questions give the book a tight analytic structure that makes it easy to compare similarities and differences among the various theories. To illustrate how the three questions are used going forward, I apply them in the Introduction to the ancient dream teachings found in the Bible, the philosophy of Aristotle, and the Oneirocriticon of Artemidorus. I’m trying to give readers a sense of how many of the ideas and theories of modern dream psychology did not appear out of the blue but have deep roots in the Western cultural tradition.

The order of chapters follows a by-now conventional chronology, starting with the dream theories of Sigmund Freud, then Carl Jung, then branching out into different versions of psychoanalytic psychology with a clinical focus (Alfred Adler, Medford Boss, Thomas French and Erika Fromm, Frederick Perls). Next are chapters about the findings of sleep laboratory researchers like Eugene Aserinsky, Nathaniel Kleitman, and J. Allan Hobson, and experimental psychologists like Jean Piaget, Calvin Hall, David Foulkes, Harry Hunt, and Ernest Hartmann. The last chapter is titled “Popular Psychology: Bringing Dreams to the Masses,” which chronicles the contributions of people who, beginning in the 1960’s and 1970’s, expanded the horizons of dream psychology both in the way they practiced dream interpretation (in group settings, not just in psychiatric sessions or sleep labs) and in the dreamers they included (all people in all cultures, not just Western therapy patients). This chapter profiled the work of Ann Faraday, Patricia Garfield, Gayle Delaney, Jeremy Taylor, Montague Ullman, Stephen LaBerge, and ends with the “Senoi Debate” between Kilton Stewart and G. William Domhoff.

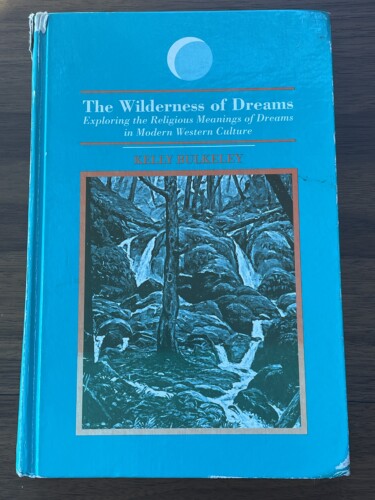

The cover was entirely out of my hands. It’s fine, I’ve come to like the blue-to-indigo colors and the cloudy sky imagery, it’s all rather trippy. We persuaded two eminent sleep laboratory researchers, Ernest Hartmann and Wilse Webb, to write back-cover endorsements. Hartmann and Webb were both in the first generation of psychologists who studied how the new findings about REM and NREM sleep relate to psychoanalytic insights about the nature of dreaming. If they were happy with the book, then mission accomplished.

The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

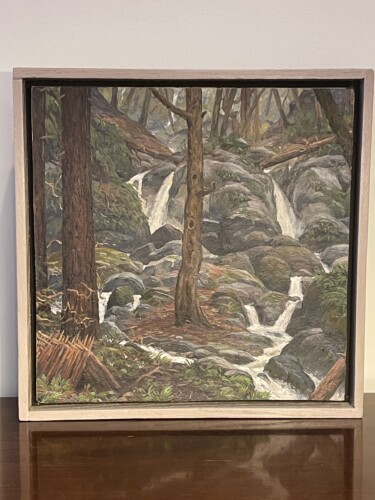

It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend

It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend

Houses and homes are among the most frequent elements appearing in dreams, with a wide range of literal and symbolic meanings.

Houses and homes are among the most frequent elements appearing in dreams, with a wide range of literal and symbolic meanings. This is a post I recently wrote about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in the practice of dream interpretation. In coordination with the team at the Elsewhere.to dream journaling app–Dan Kennedy, Gez Quinn, and Sheldon Juncker–we have been experimenting with “Freudian” and “Jungian” modes of interpretation, and the results are very encouraging. Maybe more than encouraging… I don’t highlight this in the post, but the AI interpretation in “Jungian” mode used the phrase “confrontation with the unconscious,” which was not part of the prompting text for the AI. In other words, the AI seems to have identified this phrase as a vital one in Jungian psychology (it’s the title of the pivotal chapter 6 of his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections) and, without any direct guidance, used it accurately and appropriately in an interpretation . I might even suspect a sly irony in using this phrase in reference to a dream of Freud’s, but that might be too much…

This is a post I recently wrote about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in the practice of dream interpretation. In coordination with the team at the Elsewhere.to dream journaling app–Dan Kennedy, Gez Quinn, and Sheldon Juncker–we have been experimenting with “Freudian” and “Jungian” modes of interpretation, and the results are very encouraging. Maybe more than encouraging… I don’t highlight this in the post, but the AI interpretation in “Jungian” mode used the phrase “confrontation with the unconscious,” which was not part of the prompting text for the AI. In other words, the AI seems to have identified this phrase as a vital one in Jungian psychology (it’s the title of the pivotal chapter 6 of his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections) and, without any direct guidance, used it accurately and appropriately in an interpretation . I might even suspect a sly irony in using this phrase in reference to a dream of Freud’s, but that might be too much… Despite the many crises afflicting the world right now, or perhaps because of them, my Muses have been quite active recently. Urgent, even. They have inspired several writing projects I hope to share soon.

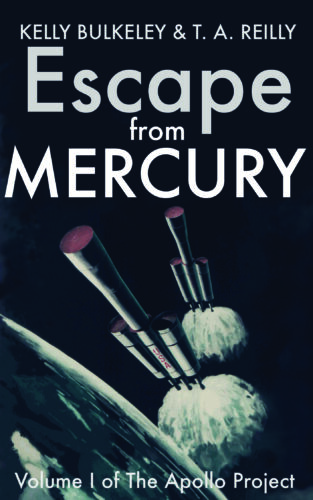

Despite the many crises afflicting the world right now, or perhaps because of them, my Muses have been quite active recently. Urgent, even. They have inspired several writing projects I hope to share soon.  Escape from Mercury – a science-fiction novel, co-edited with T.A. Reilly, in production with a private publisher, to be released on 1/1/22 at 13:00 ICT. The novel portrays an alternate history in which NASA launches a manned mission to the planet Mercury on December 3, 1979, using Apollo-era rocketry that was specifically designed for post-Lunar flights. In the present “real” timeline, those plans were abandoned. The novel reimagines the US space program continuing onward and aggressively pushing beyond the Moon, and suddenly discovering dimensions of our interplanetary neighborhood unforeseen by any but the darkest of Catholic demonologists. “The Exorcist in Space” is the tagline.

Escape from Mercury – a science-fiction novel, co-edited with T.A. Reilly, in production with a private publisher, to be released on 1/1/22 at 13:00 ICT. The novel portrays an alternate history in which NASA launches a manned mission to the planet Mercury on December 3, 1979, using Apollo-era rocketry that was specifically designed for post-Lunar flights. In the present “real” timeline, those plans were abandoned. The novel reimagines the US space program continuing onward and aggressively pushing beyond the Moon, and suddenly discovering dimensions of our interplanetary neighborhood unforeseen by any but the darkest of Catholic demonologists. “The Exorcist in Space” is the tagline. 2020 Dreams – a digital project co-authored with Maja Gutman, under contract with Stanford University Press as part of their new Digital Projects Program. We are looking at a large collection of dreams that people experienced during the year 2020, and using a variety of cutting-edge tools of data analysis and visualization to highlight patterns in the dreams and their meaningful connections to major upheavals in collective life–the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental disasters, protests for social justice, and the US Presidential election. We have just reached an agreement with the Associated Press (AP) to use their news data from 2020 as our waking-world comparison set. Our hope is to expand on the findings of Charlotte Beradt and others who have shown how dreams can reflect the impact of collective realities on individual dreams, thus providing a potentially powerful tool of social and cultural analysis.

2020 Dreams – a digital project co-authored with Maja Gutman, under contract with Stanford University Press as part of their new Digital Projects Program. We are looking at a large collection of dreams that people experienced during the year 2020, and using a variety of cutting-edge tools of data analysis and visualization to highlight patterns in the dreams and their meaningful connections to major upheavals in collective life–the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental disasters, protests for social justice, and the US Presidential election. We have just reached an agreement with the Associated Press (AP) to use their news data from 2020 as our waking-world comparison set. Our hope is to expand on the findings of Charlotte Beradt and others who have shown how dreams can reflect the impact of collective realities on individual dreams, thus providing a potentially powerful tool of social and cultural analysis. The Scribes of Sleep: Insights from People Who Keep Dream Journals – a non-fiction book in psychology and religious studies. Currently being written, under contract with Oxford University Press, likely publication in early 2023. This book brings together many sources of research about people who record their dreams over time, and what they learn from the practice. Seven historical figures are the primary case studies in the book: Aelius Aristides, Myoe Shonin, Lucrecia de Leon, Emanuel Swedenborg, Benjamin Bannecker, Anna Bonus Kingsford, and Wolfgang Pauli. A close look at their lives, their dreams, and their creative works (religiously, artistically, scientifically) suggests that keeping a dream journal seems to appeal to people with a certain kind of spiritual attitude towards the world. The stronger argument is that keeping a dream journal actively cultivates such an attitude….

The Scribes of Sleep: Insights from People Who Keep Dream Journals – a non-fiction book in psychology and religious studies. Currently being written, under contract with Oxford University Press, likely publication in early 2023. This book brings together many sources of research about people who record their dreams over time, and what they learn from the practice. Seven historical figures are the primary case studies in the book: Aelius Aristides, Myoe Shonin, Lucrecia de Leon, Emanuel Swedenborg, Benjamin Bannecker, Anna Bonus Kingsford, and Wolfgang Pauli. A close look at their lives, their dreams, and their creative works (religiously, artistically, scientifically) suggests that keeping a dream journal seems to appeal to people with a certain kind of spiritual attitude towards the world. The stronger argument is that keeping a dream journal actively cultivates such an attitude…. Here Comes This Dreamer: Practices for Cultivating the Spiritual Potentials of Dreaming – a non-fiction book addressed to general readers interested in deeper explorations of their dreaming. Currently being written, under contract with Broadleaf Books, likely publication in the latter part of 2023. The challenge here, both daunting and exciting, is explaining the best findings from current dream research in terms that “curious seekers” will find meaningful and personally relevant. The book will have three main sections: 1) Practices of a Dreamer, 2) Embodied Life, and 3) Higher Aspirations. The title of the book signals a key concern I want to highlight: to be a big dreamer, like Joseph in the Bible (Gen. 37:19), can be amazing and wonderful, but it can also be perceived by others as threatening and dangerous. Sad to say, the world does not always appreciate the visionary insights of people who naturally have vivid/frequent/transpersonal dreams. I want to share what I hope are helpful and reassuring ideas about how to stay true to your innate dreaming powers while living in a complex social world where many people are actively hostile to the non-rational parts of the mind.

Here Comes This Dreamer: Practices for Cultivating the Spiritual Potentials of Dreaming – a non-fiction book addressed to general readers interested in deeper explorations of their dreaming. Currently being written, under contract with Broadleaf Books, likely publication in the latter part of 2023. The challenge here, both daunting and exciting, is explaining the best findings from current dream research in terms that “curious seekers” will find meaningful and personally relevant. The book will have three main sections: 1) Practices of a Dreamer, 2) Embodied Life, and 3) Higher Aspirations. The title of the book signals a key concern I want to highlight: to be a big dreamer, like Joseph in the Bible (Gen. 37:19), can be amazing and wonderful, but it can also be perceived by others as threatening and dangerous. Sad to say, the world does not always appreciate the visionary insights of people who naturally have vivid/frequent/transpersonal dreams. I want to share what I hope are helpful and reassuring ideas about how to stay true to your innate dreaming powers while living in a complex social world where many people are actively hostile to the non-rational parts of the mind.