This is an excerpt from a panel on dream education at the recent conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams. My co-panelists were Phil King and Bernard Welt, with whom I wrote Dreaming in the Classroom: Practices, Methods, and Resources in Dream Education.

This is an excerpt from a panel on dream education at the recent conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams. My co-panelists were Phil King and Bernard Welt, with whom I wrote Dreaming in the Classroom: Practices, Methods, and Resources in Dream Education.

Any class on dreams that occurs within a school context must, at a minimum, provide educational benefits consistent with the school’s mission. These benefits usually include critical thinking, literacy skills, knowledge acquisition, global citizenship, etc. All of us on the panel agree that classes on dreams can do a wonderful job of providing these educational benefits and contributing to the general goals of almost any kind of school.

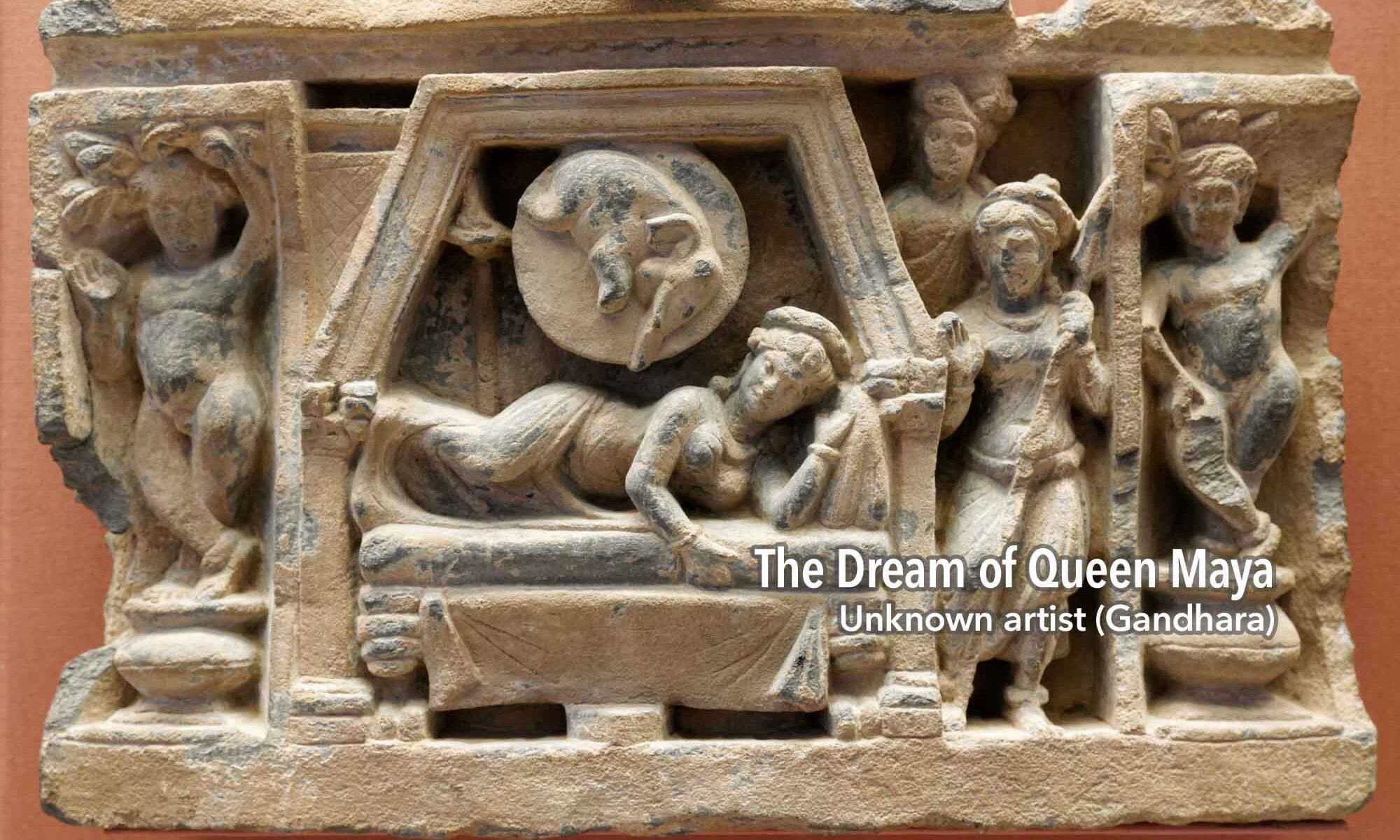

But dream classes can do more than that. Indeed, dream classes are always doing more than that, whether or not the teacher and students are explicitly aware of it. Something happens when dreams enter the classroom, something very different from other topics of study. Each of us on the panel has different ways of talking about that educational surplus. For me, what’s interesting is how every class on dreams becomes at some level a class on religious studies. By that I mean a class that studies human expressions of ultimacy via symbols, metaphors, and myths. The historical aspect of this may be most obvious. Prior to the rise of psychology as a Western academic discipline in the mid-nineteenth century, the primary arena in which people shared, discussed, and explored their dreams was religion–in Hinduism, Buddhism, Daoism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and the spiritual traditions of the indigenous peoples of Africa, the Americas, and Oceania. Any class that’s trying to provide a solid base of knowledge about dreams can’t ignore the history of religions. This is true whether you are teaching in psychology, literature, biology, or any other discipline—as soon as you start telling your students about dreams, you’ll need to talk about religious history, too.

I understand this might seem daunting to educators without any training or background in comparative religious studies. I’m not saying you have to include large amounts of this material in your curriculum. But I am saying you should think carefully about how you’re going to present the topics of your class within this bigger historical framework. You should let your students know there IS a bigger historical framework, even if that’s not the specific focus of your class.

There’s another way that dream classes become religious studies classes, even more important than the historical aspect. Whenever dreams become a topic of classroom discussion, the students are inevitably prompted to reflect on their private dream experiences. The class may not explicitly involve personal dream sharing, or keeping a journal, or anything directly about the students’ own dreams—but I guarantee you, the students are thinking about their dreams in relation to what’s coming up in the class. Especially if the teacher is a good one and gets the students excited about the topic, they’re going to be curious to explore their own dreams. And once they do that, they’re very likely to come across themes, questions, and experiences that go to the heart of many of the world’s religions—for example, the prospect of death and an afterlife, the struggle of good and evil, the illusory nature of reality, prophetic anticipations of the future, nightmarish suffering and existential dread, haunting encounters with supernatural beings, and so forth.

Teachers can ignore all this if they wish, but I think it’s better if they at least recognize that their students are wondering about these kinds of issues in their dreams and thinking about how the class is, or is not, helping them make better sense of their experiences. Again, this doesn’t mean you have to devote extensive class time to the religious implications of dreams in people’s lives. You could devote some time to this topic, of course, and I think you’d be surprised at what your students would say if given the chance! But it’s enough if you simply let the students know that, just as people in the past drew religious inspiration and philosophical insight from dreams, so do many people today. It’s not a matter of ancient superstition carrying over into the modern world, but rather a recognition that humans in all times and places, up to and including us today, are dreamers, and our dreams bring us into contact with ideas, feelings, and energies that most cultures through history have regarded as religiously meaningful. Whether or not we use religious language, the personal impact of certain dreams can be intensely meaningful and even transformative. As dream educators, we have to give our students some degree of informed awareness of those spiritual dimensions of dreaming potential.

![62242_cov[1]](https://www.bulkeley.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/62242_cov12-200x301.jpg)