Uncanny dreams and deathly sleep haunt the most famous lovers in literary history.

The woeful story of Juliet and her Romeo has several ominous references to beds, sleep, and dreams. These nocturnal elements reflect the tension between the passionate yearnings of the young lovers and the tragic fate that awaits them. As Friar Laurence vainly warns, “these violent delights have violent ends.” Romeo and Juliet discover both ecstatic delights and annihilating ends in the darkest, dreamiest realms of night.

Romeo’s First Dream and Mercutio’s “Queen Mab” Speech

In one of the early scenes of the play (currently in production at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, with Emily Ota as Juliet and William Thomas Hodgson as Romeo), a moment of witty banter suddenly turns into a long, weirdly unsettling monologue about the nature of dreaming. It is, I believe, the most extensive treatment of dreams in all of Shakespeare’s works, and it encapsulates in a single surreal passage the inspiring-yet-terrifying energies of human dream experience.

At the start of Act I, scene iv, Romeo meets with his friends Mercutio and Benvolio on a street outside the family house of the Capulets, sworn enemies of Romeo’s family, the Montagues. The Capulets are hosting a feast and masquerade ball, and Mercutio, Benvolio, and Romeo have decided to wear masks and sneak into the party. Just before entering the house, however, Romeo abruptly stops and questions the wisdom of their plan. Even though the woman he desperately loves, Rosaline, will be attending the festivities, he worries that something bad will happen if they go forth. Mercutio demands that Romeo explain his sudden misgivings, and the following exchange ensues:

Romeo: I dreamt a dream tonight.

Mercutio: And so did I.

Romeo: Well, what was yours?

Mercutio: That dreamers often lie.

Romeo: In bed asleep, while they do dream things true.

(1.4.51-56)

Romeo believes his dream is warning him of danger in the future. Mercutio is more interested in the party, however, and he tries to deflect Romeo’s gloomy prognostication with a sharp-edged jest: he lures Romeo into asking him if he really had a dream, and then calls into question the veracity of anyone who claims to have a dream to tell. But Romeo has a strong feeling about the potential significance of his dream, and he tries to persuade Mercutio to take it seriously.

Romeo gets more than he bargained for. Mercutio launches into an elaborate and fanciful speech that covers more than forty lines of text, starting with this:

Mercutio: O, then I see Queen Mab hath been with you. She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes in shape no bigger than an agate stone…

(I.iv.57-59)

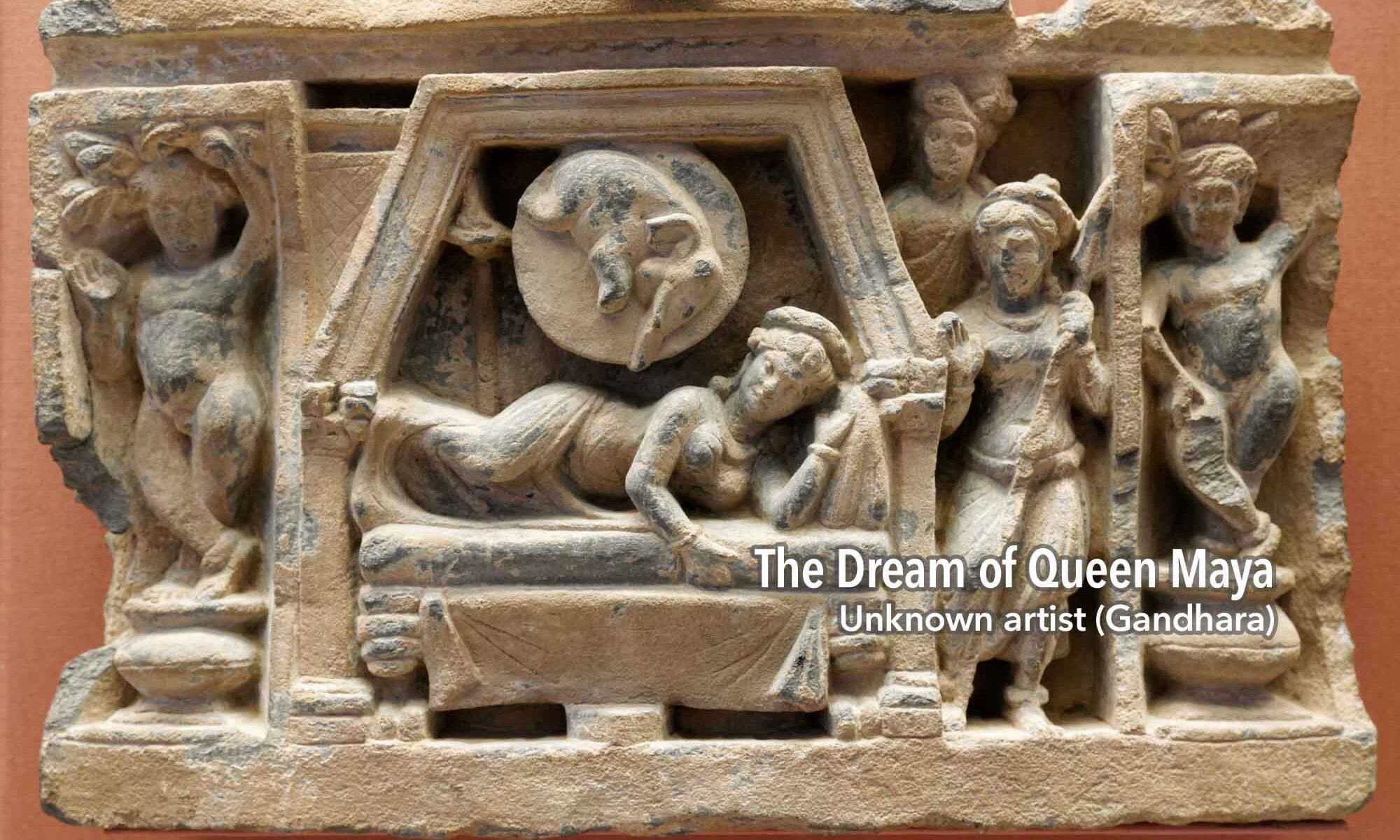

What follows is a strange, magical journey into the realm of the fairies and their nocturnal activities. As he does at greater length in the romantic fantasy “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” also written around this same time (1595-1596), Shakespeare draws upon popular folklore to envision a colorful world of tiny tricksters who, hovering just outside the range of our ordinary awareness, are busily influencing our lives in ways both fair and foul. Despite her miniscule size and delicate nature, Queen Mab wields total power over us when we sleep and dream. Mercutio goes on describe what happens when she visits various kinds of people in their slumber:

Mercutio: And in this state she gallops night by night through lovers’ brains, and then they dream of love; O’er courtiers knees, that dream on curtsies straight; O’er lawyers fingers, who straight dream on fees; O’er ladies’ lips, who straight on kisses dream.

(I.iv.74-78)

What Mercutio describes is quite similar to the continuity hypothesis of dreaming, which states that people tend to dream most frequently about things that emotionally concern them in waking life. Lovers dream of love, courtiers dream of kneeling in court, lawyers dream of receiving money from clients—whatever is most important in a person’s life, that’s what they’re most likely to dream about. Mercutio describes other examples of Queen Mab’s dream-stimulating activities: she tickles a minister’s nose, and he dreams of a financially secure job; she drives over a soldier’s neck, and he dreams of cutting enemy throats. The common thread throughout these examples is that dreams are personalized reflections of people’s current concerns and not, as Romeo assumes, prophecies about the future. In this regard, Mercutio’s speech is a remarkable anticipation of a modern psychological theory about dreaming.

Queen Mab takes mischievous delight in causing chaos and disorder, a fairy trait she shares with Puck, Oberon, and Titania in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” As Mercutio continues his speech, this quality comes to the fore, and at a certain point Mercutio seems to lose control of his own story:

Mercutio: This is the very Mab that plaits the manes of horses in the night and bakes the elflocks in foul sluttish hairs, which once untangled much misfortune bodes. This is the hag, when maids lie on their backs, that presses them and learns them first to bear, making them women of good carriage. This is she—

(I.iv.92-98)

Here, Shakespeare condenses several folk-beliefs about the dark forces behind dreaming. Queen Mab morphs into a relentless incubus or night hag who tangles hair, presses on bodies, preys on fears, and forces sexual submission. She is the embodiment of all the nightmarish powers set loose within our sleep, and she devotes especially malicious attention to the torments of “sluttish” young women. The physiological effects described here could, in modern terms, be diagnosed as night terrors, with the sensation of pressure and feelings of overwhelming fear. They could also be explained in terms of psychoanalytic theory: Queen Mab is the primal Id of the human unconscious, running wild through our dreams while the ego slumbers in blissful ignorance.

Most productions of the play have Mercutio delivering these final lines of his speech in a manic frenzy, as the fairies’ malevolent mayhem threatens to overwhelm him. The OSF version, with the incandescent Sara Bruner as Mercutio, follows that traditional staging, but with an intriguing gender twist that gives the speech a deeper level of emotional resonance.

At this point, Mercutio has become so unhinged that Romeo steps forward to interrupt him and snap him out of the psychotic spell of his own words. Now it’s Romeo’s turn to play down the significance of dreams, in an effort to calm his friend’s frazzled nerves:

Romeo: Peace, peace, Mercutio, peace! Thou talk’st of nothing.

(I.iv.100-101)

Mercutio responds with another unexpected shift of tone and attitude:

Mercutio: True, I talk of dreams; which are the children of an idle brain, begot of nothing but vain fantasy; which is as thin of substance as the air, and more inconstant that the wind…

(I.iv.102-106)

After dwelling at such length on the wondrous exploits of Queen Mab and her fairy consorts, Mercutio abruptly concludes with a rejection of dreaming as a whole. A modern materialist could not express any more eloquently the idea that dreams are sheer nonsense. Here, Mercutio is anticipating the basic themes of neuroscientific reductionism, another strand of current thinking about dreams that treats them as the disordered and meaningless by-products of an “idle brain” during sleep.

In the context of the play and this particular scene, Mercutio’s claim is not very persuasive, since he just spent several minutes giving a highly detailed account of the meaningful connections between people’s dreams and their waking lives. Indeed, his belated rejection of dreaming seems more like a desperate attempt to deny what he has just openly acknowledged to be real and true. He’s trying to put the lid back on the magic box, but it’s too late. The fairies have already escaped.

Benvolio finally draws their attention back to the matter at hand, and on they go to the party. But Romeo has been deeply rattled. More than ever, he feels a prophetic sense of darkening gloom ahead and the inescapable prospect of “untimely death.”

So this is Romeo’s frame of mind when he puts on his mask and walks into the party at the Capulets. He is deeply depressed about his unrequited love for Rosaline; he just had a very worrisome dream portending some future ill; and his friend nearly goes mad talking about the supernatural powers of malicious mischief set loose in our dreams. Plus, he knows that if his true identity is discovered, he will likely be killed. By entering the party, Romeo is entering a perilous, uncertain, and potentially transformative space.

Juliet’s Merging of Beds, Sleep, and Death

We do not know what Juliet dreams about. We only know what she does not dream about. In her first appearance, Juliet’s mother calls for her to discuss an important question:

Capulet’s wife: Tell me, daughter Juliet, how stands your disposition to be married?

Juliet: It is an honor that I dream not of.

(I.iii.68-70)

Juliet’s reply is both modest and diplomatic. As an obedient and virtuous daughter, she accepts that her parents will decide when, where, and to whom she will be pledged in the sacred bond of marriage. Until that time, the topic is the farthest thing from her mind, something that does not even appear in her dreams. Her reply also includes a subtle degree of reluctance to think about marriage at this stage of life. Her nurse has just given a long and rambling speech, the upshot of which is that Juliet is not yet 14 years of age, barely past childhood. But Juliet’s mother insists that other “ladies of esteem” in Verona are married by this age and already bearing children, as did she when she first married Juliet’s father.

This is preamble to dramatic news. Her mother says that a well-regarded gentleman by the name of Paris has shown marital interest in Juliet (he “seeks you for his love”), and he has come to their house that very evening to win her hand. Juliet’s mother gives her virtually no time to react—“speak briefly, can you like of Paris’ love?” Juliet dutifully answers that she will try to like him, but no more than her mother says she should. The nurse shows no such reluctance, as she makes abundantly clear the sexual implications of this sudden turn of events: “Women grow by men… Go, girl, seek happy nights to happy days.”

Juliet speaks very few lines in this scene, which is fitting since she really has no say in any of these choices or decisions. She dreams of none of this because she has no agency, no creative investment in any of it; it all happens to her, by decree of her parents, leaving her imagination no reason to wonder about alternative possibilities.

So this is Juliet’s frame of mind when she puts on her mask and joins her family’s feast. After dwelling on the fact that she is currently 13 years old, she is informed by her mother that she has reached a marrying age, that a particular gentleman has already expressed his romantic interest in her, and that said gentleman is present in their home right now, ready to secure her affections. Thanks to the nurse’s bawdy commentary, she cannot avoid the reality that she will be expected to engage in sexual relations with him. Thus when she goes to the party, Juliet enters a perilous, uncertain, and potentially transformative space.

And once there, she meets Romeo. Their magical first encounter surprises them both; this is not what they were expecting when they walked into the party. Completely forgetting the people they were supposed to seek (Rosaline for Romeo, Paris for Juliet), they almost instantly fall in love with a masked stranger, in a moment of mysteriously intense romance.

When the gathering ends, Juliet anxiously begs the nurse:

Juliet: Go ask his name.—If he be married, my grave is like to be my wedding bed.

(I.v.73-74)

This is the first of many instances in which Juliet and other characters make symbolic connections between beds, sleep, and death. These references are also intertwined with the bed as a physical space for passion, love, and the creation of new life. The grave and the wedding bed—they occupy opposite ends of an existential spectrum, and yet in this story they inexorably draw towards each other and finally merge into a tragic unity.

The early references are the happiest. As Romeo stands beneath Juliet’s balcony exchanging vows of love, he marvels at the incredible magic of the moment:

Romeo: O blessed, blessed night! I am afeard, being in night, all this is but a dream, too flattering-sweet to be substantial.

(II.ii147-149)

A few moments later he bids a final farewell to Juliet at her balcony:

Romeo: Sleep dwell upon thine eyes, peace in thy breast! Would I were sleep and peace, so sweet to rest!

(II.ii.202-203)

After the friar performs their secret wedding, Juliet eagerly anticipates her first opportunity to be alone with her husband:

Juliet: Come, night; come, Romeo; come, thou day in night; for thou wilt lie upon the wings of night whiter than new snow upon a raven’s back. Come, gentle night; come, loving, black-browed night; give me my Romeo…

(III.ii.17-21)

Romeo and Juliet finally get to celebrate their marriage with a “love-performing night” together in her bed (III.v), and they lament the coming of the day (Romeo says, “I must be gone and live, or stay and die”).

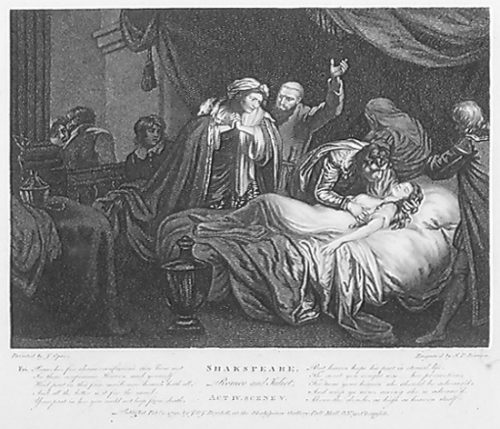

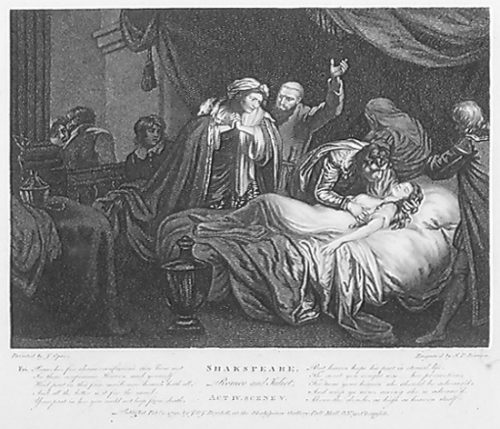

Now everything darkens, and fate closes in on the young couple. After they part, Juliet learns that she will soon be wedded to Paris, while Romeo finds he has been exiled from Verona for the killing of Juliet’s brother Tybalt in a street brawl. With the friar’s help, Juliet decides to take a sleeping potion that will “wrought on her the form of death”:

Friar Laurence: And in this borrowed likeness of shrunk death thou shalt continue two and forty hours, and then awake as from a pleasant sleep. Now, when the bridegroom [Paris] in the morning comes to rouse thee from thy bed, there art thou dead.

(IV.i.106-110)

The friar promises to tell Romeo to go to Juliet in the Capulet tomb after she has revived, so they can secretly escape the city together. Alas, the plan goes badly awry. Paris gets to the tomb first, and mourns at what he believes to be the dead Juliet’s side:

Paris: Sweet flower, with flowers thy bridal bed I strew—O woe! Thy canopy is dust and stones.

(V.iii.12-13)

Then Romeo enters the tomb. Paris draws his sword and attacks; Romeo kills him. He then goes to Juliet’s motionless body and falls for the deception, too: he thinks she is truly dead. Unable to distinguish death from sleep, Romeo decides to join her in death. Immediately upon his doing so, Juliet awakens. The friar arrives at this point, and he urges Juliet to leave at once:

Friar Laurence: I hear some noise. Lady, come from that nest of death, contagion, and unnatural sleep.

(V.iii.156-157)

Juliet refuses. Instead, she decides to join her beloved Romeo in eternal slumber. After a final kiss, she takes his dagger and presses its point against her chest:

Juliet: This is thy sheath; there rest, and let me die.

(V.iii.175)

Romeo’s Joyful Dream

The agonizing conclusion to the story makes it all the more peculiar that, just before he learns of Juliet’s apparent death, Romeo awakens with a happy dream. His speech at the start of Act V is a final beam of light in the gathering darkness:

Romeo: If I may trust the flattering truth of sleep, my dreams presage some joyful news at hand. My bosom’s lord sits lightly in his throne, and all this day an unaccustomed spirit lifts me above the ground with cheerful thoughts. I dreamt my lady came and found me dead (strange dream that gives a dead man leave to think!) and breathed such life with kisses in my lips that I revived and was an emperor. Ah me! How sweet is love itself possessed, when but love’s shadows are so rich in joy!

(V.i.1-11)

What are we to make of this dream? At one level it seems horribly misleading—Romeo is about to receive absolutely terrible news about Juliet, and death will soon consume them both. The dream seems like a cruel hoax, and a painfully ironic example of why we should not “trust the flattering truth of sleep.”

But at another level, perhaps the dream is leading Romeo towards an awareness of a different realm of union with Juliet, a transcendent realm where he will be “an emperor,” and where life will conquer death. For the truth is, there is no hope in the present waking world for him and Juliet, not with their families’ violent hatred of each other. Romeo’s dream offers him an alternative way of understanding what the future is about to bring. Their love is, by its very existence, a miraculous triumph over the rigid constraints that govern their lives. They have successfully defied the social authorities and asserted their own desires for romantic fulfillment. Their kisses have the power to transport them beyond the petty feuds of this world to a beautiful and joyful world all their own.

Romeo notes the strange element in his dream of a dead man thinking living thoughts. Today we might call this a variation on metacognition in dreaming, a type of “thinking about thinking.” Here, it’s Romeo thinking about what he would be thinking if he were dead. This seems impossible from a conventional waking perspective, just as it’s impossible that he could ever actually become an emperor in the waking world. But these things are possible in the realm of dreaming, and this suggests an expansion of normal awareness, a dissolving of ordinary boundaries, and the discovery of new potentials beyond the limits of the present. That does seem to be the tangible effect of the dream on Romeo once he awakens. It breaks through his fears, lifts his spirits, and stimulates a welcoming attitude towards the future. For one last moment he feels pure lightness and joy, and he revels in the wonders of his love for Juliet.

Is that a cruel deception, or a profoundly truthful vision?

Earlier in the play, Mercutio gives a variety of reasons why we should ignore dreams: dreamers lie, the fairies manipulate people’s minds, and anyway it’s all nonsense from the sleep-addled brain. But by the end of the play the references to dreams shift towards an emphasis on their accuracy in reflecting reality. After killing Paris in the Capulet tomb, Romeo briefly wonders about something his servant, Balthasar, said to him on the way to the tomb:

Romeo: I think he told me Paris should have married Juliet: Said he not so? Or did I dream it so?

(V.iii.78-79)

Balthasar probably did say so, but for Romeo it could equally have been a dream; all are one in his mind now.

A few moments later, Friar Laurence encounters Balthasar outside the tomb. Romeo had told Balthasar to wait for him, and under no circumstances to follow him into the tomb. Now Balthasar anxiously tells the friar he fears something terrible has happened:

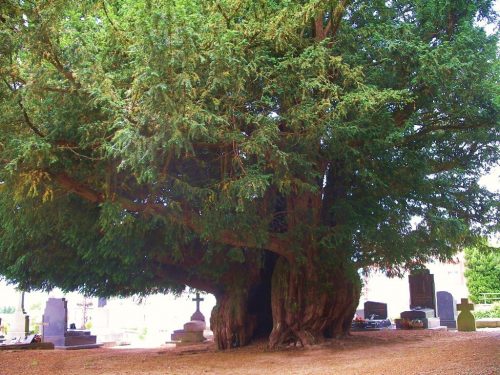

Balthasar: As I did sleep under this yew-tree here, I dreamt my master and another fought, and that my master slew him.

(V.iii.141-143)

The staging of the scene leaves Balthasar’s exact position unclear (“I’ll hide me hereabout”), so we don’t know if he saw or heard Romeo and Paris while they were fighting; either way, Balthasar’s dream accurately reflects what did in fact happen in the tomb.

In both instances during this final climactic scene of the play, the distinction has dissolved between dreaming and waking reality. Dreams have become transparent to the actuality of what’s happening in this world. That is the final, spiritually illuminating context for Romeo’s joyful dream and its flattering truth about the eternal love he shares with Juliet.

####

Yew tree photo is from Roi.dagobert

Before going to bed each night after a long day of rehearsals, the director of “Alice in Wonderland” wrote a letter, sealed it, and put it under her pillow. The letter was addressed to her theatrical hero, Eva Le Gallienne (1899-1991), a revolutionary figure on the American stage whose adaptation of the Alice stories was first presented in the early 1930’s at the Civic Repertory Theater in New York City, which she founded with the mission of providing the highest-quality dramatic artistry for the widest possible audience.

Before going to bed each night after a long day of rehearsals, the director of “Alice in Wonderland” wrote a letter, sealed it, and put it under her pillow. The letter was addressed to her theatrical hero, Eva Le Gallienne (1899-1991), a revolutionary figure on the American stage whose adaptation of the Alice stories was first presented in the early 1930’s at the Civic Repertory Theater in New York City, which she founded with the mission of providing the highest-quality dramatic artistry for the widest possible audience.

Shakespeare’s most cunning villain turns sleep and dreaming against his enemies.

Shakespeare’s most cunning villain turns sleep and dreaming against his enemies.

Peeling away Freudian assumptions to reach a deeper human truth about the capacity to love.

Peeling away Freudian assumptions to reach a deeper human truth about the capacity to love. A quick recap of the plot: Set in the Oklahoma territory in 1906, just before official statehood, the story revolves around two love triangles. In one, a cowboy (Curly) and a farmhand (Jud) vie for the affections of a farmer’s daughter (Laurey). In the other, cowboy Will Parker and Ali Hakim, a Persian traveling salesman, are both involved with Ado Annie, one of Laurey’s girlfriends.

A quick recap of the plot: Set in the Oklahoma territory in 1906, just before official statehood, the story revolves around two love triangles. In one, a cowboy (Curly) and a farmhand (Jud) vie for the affections of a farmer’s daughter (Laurey). In the other, cowboy Will Parker and Ali Hakim, a Persian traveling salesman, are both involved with Ado Annie, one of Laurey’s girlfriends. A brilliant exploration of the dark psychological depths of sexual desire appears in an unlikely place—a country musical from the 1940’s.

A brilliant exploration of the dark psychological depths of sexual desire appears in an unlikely place—a country musical from the 1940’s.

In the next scene a supremely confident Master Ford brings a group of companions to his house to apprehend Falstaff. His wife, in the midst of sending out the dirty laundry, denies that Sir John is there. Master Ford contemplates the laundry basket, which is about to be sent out for “buck-washing” (a traditional means of laundering clothes by soaking and rinsing them repeatedly with lye, ash, or urine), and utters some strange lines: “Buck? I would I could wash myself of the buck! Buck, buck, buck! Ay, buck; I warrant you, buck—and of the season too, it shall appear” (III.iii.155-157).

In the next scene a supremely confident Master Ford brings a group of companions to his house to apprehend Falstaff. His wife, in the midst of sending out the dirty laundry, denies that Sir John is there. Master Ford contemplates the laundry basket, which is about to be sent out for “buck-washing” (a traditional means of laundering clothes by soaking and rinsing them repeatedly with lye, ash, or urine), and utters some strange lines: “Buck? I would I could wash myself of the buck! Buck, buck, buck! Ay, buck; I warrant you, buck—and of the season too, it shall appear” (III.iii.155-157).