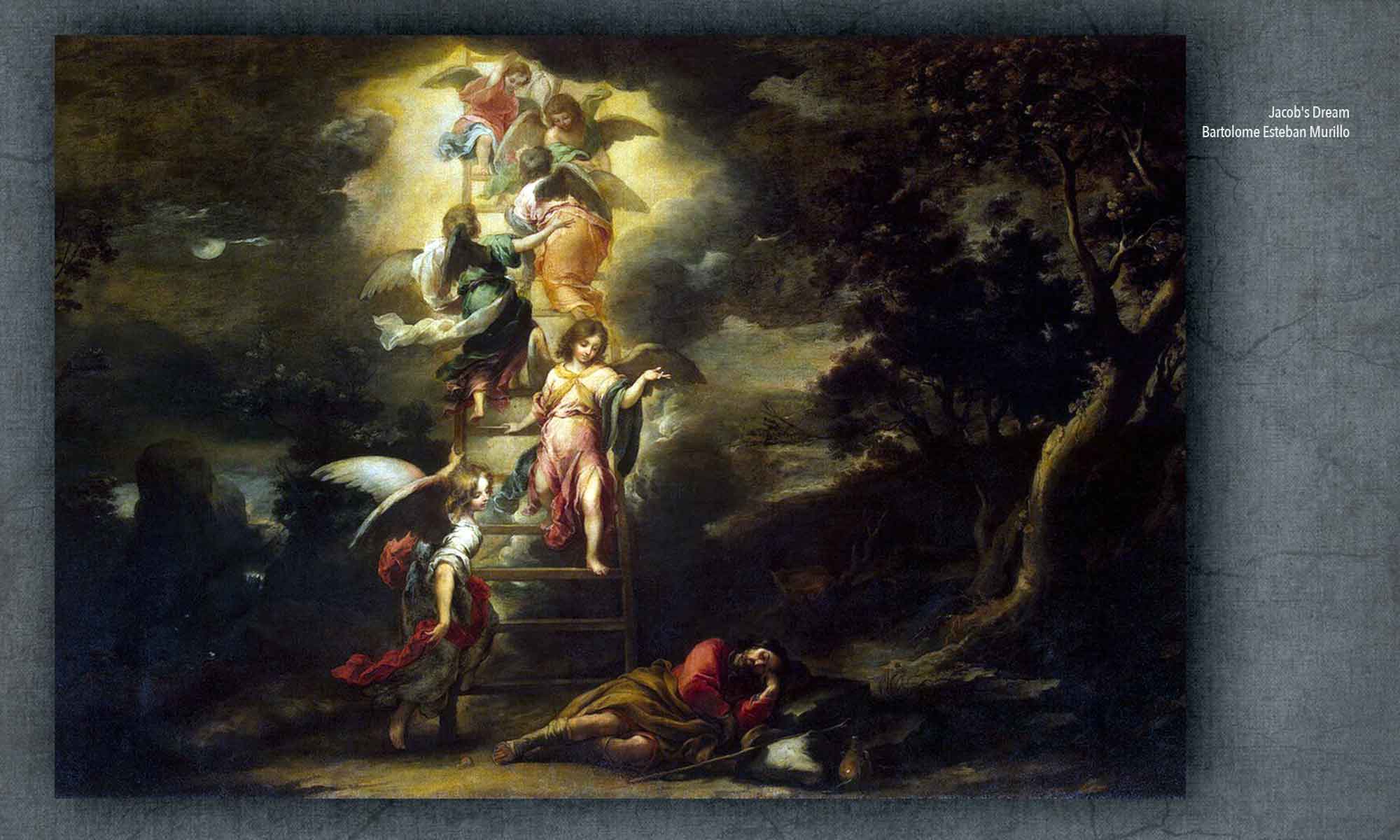

More than four hundred million people, most of them children and teenagers, have read the Harry Potter novels of J.K. Rowling, immersing themselves in a fantastical world in which broomsticks fly, portraits talk, wizards cast spells–and dreams reveal honest emotional truths. Rowling’s hugely popular stories about the magical education of young Harry Potter abound with dream experiences that weave prophetic visions with psychologically astute insights into adolescent feelings of loss, fear, desire, and hope. Looking closely at the roles played by dreaming across all seven novels, it becomes clear that readers of these books are well primed to regard dreams as a piece of magic, as a mysterious, potentially dangerous, but extremely valuable source of power, meaning, and guidance in life. Rowling’s fantasy tale carries a message of real-world significance: We Muggles (non-wizards) may not be able to fly on brooms or cast spells, but we do possess the magical power of dreaming.

More than four hundred million people, most of them children and teenagers, have read the Harry Potter novels of J.K. Rowling, immersing themselves in a fantastical world in which broomsticks fly, portraits talk, wizards cast spells–and dreams reveal honest emotional truths. Rowling’s hugely popular stories about the magical education of young Harry Potter abound with dream experiences that weave prophetic visions with psychologically astute insights into adolescent feelings of loss, fear, desire, and hope. Looking closely at the roles played by dreaming across all seven novels, it becomes clear that readers of these books are well primed to regard dreams as a piece of magic, as a mysterious, potentially dangerous, but extremely valuable source of power, meaning, and guidance in life. Rowling’s fantasy tale carries a message of real-world significance: We Muggles (non-wizards) may not be able to fly on brooms or cast spells, but we do possess the magical power of dreaming.

The first time we meet Harry, in the opening pages of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, he is waking up in the tiny coat closet where his dim-witted Muggle relatives the Dursleys have kept him hidden for the past ten years. Harry “rolled onto his back and tried to remember the dream he had been having. It had been a good one. There had been a flying motorcycle in it. He had a funny feeling he’d had the same dream before.” (1.19) When Harry mentions the dream to the Dursleys on a family drive to the Zoo, Mr. Dursley, introduced to readers as someone who “didn’t approve of imagination” (1.5), angrily shouts that motorcycles don’t fly. Taken aback, Harry replies, “I know they don’t, it was only a dream.” (1.25) What he does not yet know is that motorcycles do fly when properly enchanted, and a flying motorcycle in fact brought him to the Dursley’s house ten years ago. His recurrent dream is not “only” a dream, but rather a meaningful and reassuring reminder of his true origins, despite the best efforts of the stubbornly pedestrian Dursleys to erase those memories from his mind. This early debate about the significance of dreams establishes a basic tension running through all the novels between the infinite potentials of the wizarding world and the anxious Muggle determination to pretend that such potentials do not exist.

After the disastrous Zoo visit, when Harry discovers he can speak to snakes and sets one loose on his cousin Dudley, the flying motorcycle returns to spirit him away on a journey to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, Harry’s home for the next several years. On his first night at Hogwarts,

“Perhaps Harry had eaten a bit too much, because he had a very strange dream. He was wearing Professor Quirrell’s turban, which kept talking to him, telling him he had to transfer to Slytherin at once, because it was his destiny. Harry told the turban he did not want to be in Slytherin; it got heavier and heavier; he tried to pull it off but it tightened painfully–and there was Malfoy, laughing at him as he struggled with it–then Malfoy turned into the hook-nosed teacher, Snape, whose laugh became high and cold–there was a burst of green light and Harry awoke, sweating and shaking. He rolled over and fell asleep again, and when he woke the next day, he didn’t remember the dream at all.” (1.130)

It’s too bad Harry forgets the dream, because it accurately reveals his ultimate challenge in this book and throughout the series: To defeat this malevolent lineage of characters from Slytherin, one of the four houses at Hogwarts, infamous for its attraction to dark magic. Draco Malfoy, Harry’s bitter rival and classmate, is a member of Slytherin house and Professor Snape, Harry’s least favorite teacher, is Slytherin house master. Though Harry does not know it yet, the high, cold laugh and the voice talking from Professor Quirrell’s turban come from his arch-enemy, the dark wizard known as Lord Voldemort (himself a former Slytherin student). The burst of green light shows Harry what a killing curse looks like—something he has seen once before, ten years earlier, when Voldemort murdered his parents.

None of this registers consciously for Harry, but it’s all laid out for readers in his first-night-at-Hogwarts dream. The talking turban directly foreshadows the climactic discovery at the end of this book that Voldemort (a tiny, shriveled being at this point) is controlling Quirrell by hiding inside the back of his turban. More broadly, the fact that Harry himself is wearing the turban anticipates a series-long struggle with his “inner Voldemort,” a struggle in which his lightning-scarred head is the primary battleground.

As the story unfolds Harry learns more about his past, the death of his parents, and his strange connection to Voldemort. Now he begins having recurrent nightmares: “Over and over again he dreamed about his parents disappearing in a flash of green light, while a high voice cackled with laughter.” (1.215) By this point Harry recognizes that this horrible scene is not “only” a dream but an actual event that happened in his past. The recurrent nightmares, like his other dreams, turn out to be legitimate memories of horrors in his past. The term “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” is never used in the books, but readers with clinical training may find it impossible to ignore that diagnosis. The long-buried memories surfacing in his dreams reveal a primal experience of severe, shocking pain.

The second novel, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, also opens with a highly significant dream that Harry ignores. The story starts with an elf servant named Dobby suddenly appearing in his room at the Dursley’s house and begging him not to go back to Hogwarts. Mr. Dursley, furious at this magical intrusion into his well-ordered home, locks Harry in his room, puts metal bars on his window, and leaves him without any food. As night comes,

“Mind spinning over the same unanswerable questions, Harry fell into an uneasy sleep. He dreamed that he was on show in a zoo, with a card reading UNDERAGE WIZARD attached to his cage. People goggled through the bars at him as he lay, starving and weak, on a bed of straw. He saw Dobby’s face in the crowd and shouted out, asking for help, but Dobby called, ‘Harry is safe there, sir!’ and vanished. Then the Dursleys appeared and Dudley rattled the bars of the cage, laughing at him. ‘Stop it,’ Harry muttered as the rattling pounded in his sore head. ‘leave me alone….cut it out….I’m trying to sleep…’” (2.23)

Harry awakens to the sound of his friend Ron Weasley ripping the bars off his window and helping him escape back to Hogwarts. This incorporation of an external stimulus into the dream is a plausible and familiar dream phenomenon, and so is the dream’s continuity with Harry’s recent interactions with Dobby and the Dursleys.

But the dream’s references also extend to broader themes in the story. The first novel began with a visit to the zoo where Dudley taunted a snake, and here at the beginning of the second novel Harry dreams of being in the same position as that captive creature, once again highlighting the eerie affinity he has with serpents. His rare magical ability as a “parsel-mouth,” i.e., someone who can speak to snakes, come to the fore in this book as he seeks to unlock the “Chamber of Secrets,” where he must battle a massive Basilisk along with a ghostly version of Voldemort. The all-caps reminder of his status as an underage wizard reflects the developmental challenge facing Harry at this stage of the series. His sense of his own magical power is growing rapidly, yet his teachers say he must wait until he’s older before using it, even though at this very moment the forces of evil are rising again—the tension of this moral dilemma puts Harry on edge throughout the series. If he doesn’t use his power right now, Voldemort may win; but if Harry succumbs to the dark temptations aroused by his own potency, Voldemort may win, too.

In Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Harry must contend with a new species of wickedness—the Dementors, guards of the wizard prison Azkaban, ghoulish creatures of death and decay who feed on souls and leave their victims empty shells of despair. The Dementors are like PTSD demons, and they affect Harry especially badly. Professor Lupin explains why: Dementors take away everything good inside you so “you’ll be left with nothing but the worst experiences of your life. And the worst that has happened to you, Harry, is enough to make anyone fall off their broom.” (3.187) Dementor attacks intermingle with Harry’s continuing bad dreams, and now he can distinguish in his memory a specific sound—his mother’s scream as Voldemort kills her. At night “Harry dozed fitfully, sinking into dreams full of clammy, rotted hands and petrified pleading, jerking awake to dwell again on his mother’s voice.” (3.184) As Harry uncovers more about his past, his initial reaction of wonder and delight at the magical world yields to an acutely painful awareness of the family he never knew and will never have.

Not that everything in Harry’s life is going badly. About midway through the third book he helps Gryffindor house win a big Quidditch match (a wizarding sport), and during the match he fights off a (false) Dementor attack by successfully casting a strong though indistinctly shaped Patronus, an advanced level charm in which the tip of one’s wand shoots a jet of silver-white light that takes the form of a specific animal. That night Harry goes to bed feeling better than he has for long time:

“[He] had a very strange dream. He was walking through a forest, his Firebolt [his Quidditch broomstick] over his shoulder, following something silvery-white. It was winding its way through the trees ahead, and he could only catch glimpses of it between the leaves. Anxious to catch up with it, he sped up, but as he moved faster, so did his quarry. Harry broke into a run, and ahead he heard hooves gathering speed. Now he was running flat out, and ahead he could hear galloping. Then he turned a corner into a clearing and—“ Suddenly Harry is awakened by a scream. It’s Ron, who says Sirius Black, the notorious outlaw, was just in their dorm room. Everyone says Ron must have been dreaming, but Ron insists it really happened.

This premature ending of the dream, just before an eagerly-sought moment of final discovery, resonates with common dreaming experience (and with literary history, e.g., Coleridge’s incomplete Kublai Khan). It also makes for a dramatic turn of events, one that Harry, Ron, and the others completely misinterpret. They assume Sirius Black is a Voldemort ally trying to kill Harry, whereas in truth Sirius is Harry’s godfather trying to protect Harry from a different agent of the Dark Lord. Harry’s father and Sirius were best friends at Hogwarts, and Sirius turns out to be the mysterious donor of the Firebolt broomstick, which Harry received from an unknown source early in the story. Harry’s father also played Quidditch, adding another layer of masculine/paternal meaning to the dream.

One need not be a zealous Freudian to recognize the phallic symbolism of flying broomsticks and silvery-white substances coming out of wands. The abrupt awakening from his dream prevents Harry from reflecting on its possible meaning, but when the story reaches its climax we realize the dream has accurately foretold the final turn of the plot. Harry’s Patronus charm, when fully formed, takes the shape of a majestic stag—the same animal his father was magically able to turn into. Just when hordes of Dementors have descended upon him, Harry finally understands that even though his father is dead, his paternal memory remains a powerful force that Harry can use to fight his enemies. In his dream Harry takes on the role of a mythic hunter being lured deeper and deeper into the forest in pursuit of an enchanted deer. Here at the end of the story he completes his heroic dream quest by fusing his power with his father’s to create a magical force for saving people, not killing them.

Most of Harry’s dreams convey meanings related to the battle with Voldemort, but sometimes they reflect his everyday concerns, even if the deeper conflicts are never far away. The night before the final Quidditch match of the season, against the team from Slytherin, Harry “slept badly” and suffered anxious dreams of bizarre misfortunes. This type of dream is familiar to anyone who has tried to sleep while worrying about a big event the next day:

“First he dreamed that he had overslept, and that Wood was yelling, ‘Where were you? We had to use Neville instead!’ Then he dreamed Malfoy and the rest of the Slytherin team arrived for the match riding dragons. He was flying at breakneck speed, trying to avoid a spurt of flames from Malfoy’s steed’s mouth, when he realized he had forgotten his Firebolt. He fell through the air and woke with a start. It was a few seconds before Harry remembered that the match hadn’t taken place yet, that he was safe in bed, and that the Slytherin team definitely wouldn’t be allowed to play on dragons.” (3.302)

Wood is the Gryffindor team captain, and Neville is a hapless Gryffindor housemate. The dream is like a prism of Harry’s current anxieties, reflecting his concerns about letting down his house, losing a competition to a hated rival, appearing weak in front of his whole school, losing his magical power, losing his ability to fly, and ultimately losing the battle against Slytherin. Harry awakens abruptly with the sensation of falling, another typical dream experience, and he has a moment of waking/dreaming uncertainty. Once fully awake he takes comfort from the fact that the dream is not literally true, although the danger posed by Slytherin’s connection to reptilian phallic aggression remains real and ever-present.

The fourth book in the series, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, marks a big leap in the length (734 pages), psychological depth, and moral complexity of the story. Harry’s surprising, unwanted entry into the Triwizard tournament leads to ridicule and social isolation at school. For most of the book he is a solitary, psychologically tormented figure brooding on feelings of shame, fear, and rage. This is a much darker novel that thrusts Harry out of the simple wonders of childhood into the bitter, complicated concerns of the adult world.

As in the first and second novels, he initially appears in book 4 in the act of awakening: “Harry lay flat on his back, breathing hard as though he had been running. He had awoken from a vivid dream with his hands pressed over his face….Harry tried to recall what he had been dreaming about before he had awoken. It had seemed so real….” (4.16-17) Despite the pain in his scar, after a few moments of thought he pieces together the scene revealed by his dream—a Muggle being murdered by Voldemort’s snake Nagini. What Harry does not know, but readers do know from the preceding chapter, is that this dream is an accurate, real-time portrayal of something that actually happened. When Harry gets out of bed and writes a letter to Sirius, he decides “there was no point putting in the dream; he didn’t want it to look as though he was too worried.” (4.25)

We know this is exactly the wrong thing to do. Ironically, Harry is replicating Mr. Dursley’s bias against a troublesome imagination.

From the start of this novel J.K. Rowling sets us up to root for Harry’s dreams and against the skepticism of his waking mind. We know his dreams are indeed telepathic and clairvoyant, giving him a potentially powerful resource in fighting Voldemort. But Harry hesitates in trusting his dreams or telling them to others, unwilling to give people another reason to ridicule him.

While Harry worries about his dream, he also faces the life-threatening challenges of the Triwizard tournament. The night before the second task, which involves finding a way to breathe underwater, Harry anxiously looks for answers in the library, and eventually falls asleep atop his books:

“The mermaid in the painting in the prefects’ bathroom was laughing. Harry was bobbing like a cork in bubbly water next to her rock, while she held his Firebolt over his head.

’Come and get it!’ she giggled maliciously. ‘Come on, jump!’

‘I can’t,’ Harry panted, snatching at the Firebolt, and struggling not to sink. ‘Give it to me!’

But she just poked him painfully in the side with the end of the broomstick, laughing at him.” (4.489)

Harry awakens in the library to the anxious poking of Dobby, who tells him what he needs to breathe underwater. The prefects’ bathroom, with its murals of mermaids, was where Harry discovered the initial clue about the breathing-underwater task. As the youngest and least popular Triwizard champion, with the suspicious eyes of everyone upon him, facing a seemingly impossible task, Harry feels utterly powerless and alone. The dream accurately reflects these feelings in the image of his prized Firebolt being snatched away by a mermaid, a creature of the water who looks down on him and mocks his impotence.

Harry’s class on Divination, taught by Professor Trelawney, comes across as the least reliable branch of magical knowledge, appealing to gullible people willing to see omens of death and doom in every cup of tea leaves. Harry doesn’t take Professor Trelawney seriously, but one afternoon toward the end of the story (in a chapter titled “The Dream”) he falls asleep in her class and finds himself “riding on the back of an eagle owl, soaring through the clear blue sky toward an old, ivy-covered house set high on a hillside.” (4.576) Inside the house Harry comes upon Voldemort, his snake Nagini, and his bumbling servant Wormtail. He watches as Voldemort tortures Wormtail and promises Nagini he will soon be feeding on Harry Potter. His scar burning his forehead, Harry awakens to the whole class staring at him and Professor Trelawney breathlessly asking to hear what he just dreamed about.

Harry brushes her off and runs to tell Professor Dumbledore, the headmaster of Hogwarts. This time Harry has no doubt that his dream contains meaningful information for the anti-Voldemort forces. To his relief, Dumbledore accepts his dream as real and significant, explaining that the failed killing curse of the Dark Lord seems to have created a psychic connection between them. Harry asks, “So you think…that dream…did it really happen?” “It is possible,” said Dumbledore. “I would say—probable.” (4.601)

In the current issue of the IASD journal Dreaming (Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 240-252) I have an article with results of a blind word search analysis of a teenage girl’s dream series. (Many thanks to the anonymous dreamer, “Bea,” and to Bill Domhoff for mediating our interactions.) The article is my latest effort at developing a method of using statistical patterns in word usage frequency to identify meaningful continuities between dream content and waking life concerns. I think the results show that we’re making good progress. Here is the abstract of the paper:

In the current issue of the IASD journal Dreaming (Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 240-252) I have an article with results of a blind word search analysis of a teenage girl’s dream series. (Many thanks to the anonymous dreamer, “Bea,” and to Bill Domhoff for mediating our interactions.) The article is my latest effort at developing a method of using statistical patterns in word usage frequency to identify meaningful continuities between dream content and waking life concerns. I think the results show that we’re making good progress. Here is the abstract of the paper: