The image-generating power of new AI systems has huge untapped potential for the practice of dream interpretation—and some potential downsides. Even more than AI interpretive texts, the dramatic power of AI interpretive images may open new vistas for exploring the meanings of dreams.

The image-generating power of new AI systems has huge untapped potential for the practice of dream interpretation—and some potential downsides. Even more than AI interpretive texts, the dramatic power of AI interpretive images may open new vistas for exploring the meanings of dreams.

The Value of Dream-Sharing

The difficulty most of us have in understanding our dreams is not because they are random nonsense but because dreams express our unconscious sense of open-ended possibility. Almost by definition, dreaming goes beyond the limits of our waking ego to consider new angles and alternate perspectives on our past experiences, current concerns, and future potentials. It is hard to understand dreams because they are continually reaching beyond where we are to explore what we might become.

This is why it can be so helpful to share dreams with other people, to benefit from the insights of their different points of view. Jeremy Taylor and Montague Ullman each developed methods for sharing dreams in virtually any social setting, whether you know the other group members or not. Their methods were designed to maximize the information gleaned from the group while minimizing the imposition of their views on the dreamer and preserving the dreamer’s sense of safety and control of the process.

New AI technology can now provide a kind of virtual dream-sharing group, offering interpretations of a dream from multiple angles. I know this best from using the Elsewhere.to dream journaling app, which has AI tools offering several interpretive modes. If you enter a dream and try each of these modes (Freudian, Jungian, Gestalt, etc.), you can experience an interesting virtual variant of a dream-sharing group, learning from the multiplicities of meanings generated by different modes.

AI Imagery

Already, AI can provide a decent simulation of a dream-sharing group in which the dreamer benefits from diverse comments and ideas. What AI can also now do, which would be very difficult to arrange with humans, is to provide in response to a dream with a variety of images in different styles. This offers an exciting new source of feedback for the dreamer, in a visual/imagistic rather than verbal/written form. For some dreams and some dreamers this may be an even more powerful interpretive method than a text-only approach.

To test the idea, I tried it with one of my own dreams, one with a strong central image that would hopefully make it easier to compare and evaluate different visual renderings. Here is the dream, titled “Space Tub”:

Some people are in space, in a space station, and their job is getting astronauts ready for their missions. But wait, I realize something is different, not right—they are preparing the astronauts to go down, not up; and when I see the vehicle in which the astronauts are to travel, I am very disappointed. It is a large white plastic tub, big enough for one person to sit in. Not very complex at all, just thin hard plastic. I am confused, this is such a simplistic device, I can’t imagine it will actually work.

The first image, above, came from Elsewhere’s Retro Camera style.

It’s a white tub, for sure. No astronauts, no space station, although it is very simple and unlikely to do what’s needed for the astronauts. Looking at the image, I realize I don’t know what the astronauts actually need. Would they like this?

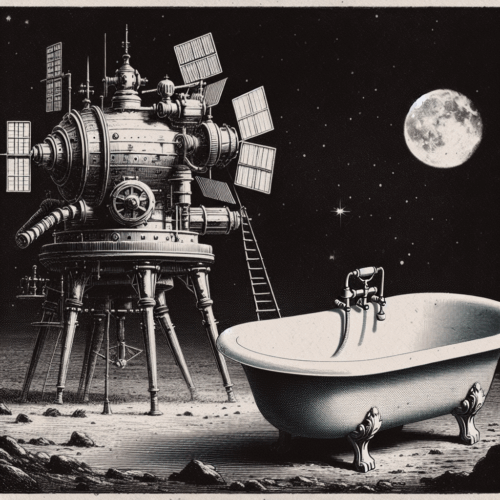

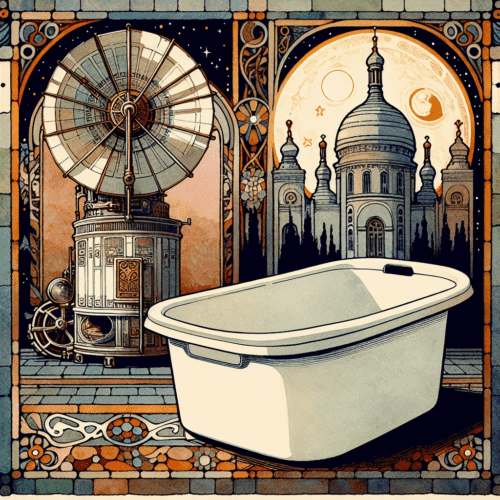

Next was the Old Illustration style:

There’s a basic anachronism in asking AI to use the style of one era to illustrate events from another era. Here, it’s a kind of steam-punk mechanism on a non-Earth planet somewhere in space. The white tub appears as a classic Victorian-era footed bathtub. This image foregrounds the themes of time and technology and makes me think of the tub in relation to water and bathing.

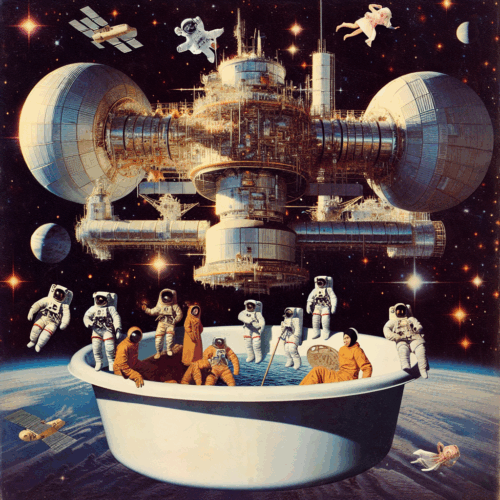

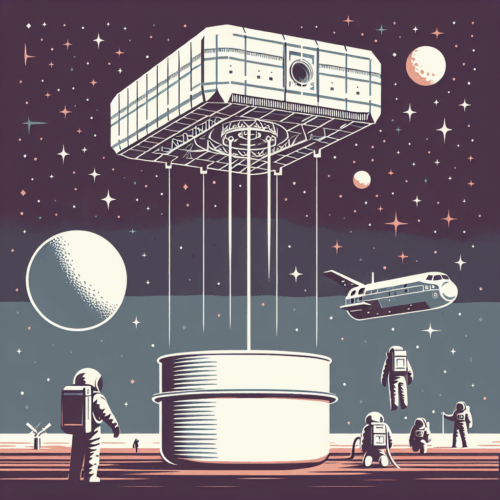

My favorite was the Surrealist Collage:

This one has a beautiful space station, a host of astronauts, and a cheap plastic bowl. It’s the only one of the three that picks up on the down/up anomaly. The tub has water in it, which isn’t the case in the dream, but the previous image also associated the tub with water, so that’s something new I can think about. It’s a very amusing image, like a party of astronauts in an orbital hot tub. That whimsical quality makes me think of the astronauts as liminal beings, or as liminal modes of being human, living in the space between heaven and earth.

None of these images is a perfect replica of my dream, but that’s okay. It’s much more stimulating to look at how the different images highlight some features and obscure others, bringing out details I might not have noticed so quickly on my own. As with any form of dream-sharing, the results can vary. Sometimes the image is completely off the mark, to the point where I get annoyed at the AI for being so obtuse. But sometimes the image is so rich and multi-faceted that I feel an immediate “aha!” of grateful insight and recognition.

Downsides

Most of the AI image-generating tools available today are enmeshed in the ethical quandaries surrounding this technology, including its smash-and-grab approach to intellectual property and its massive hunger for energy. How we resolve those issues is still an open question. Also concerning is the bias of AI systems toward the expected and familiar, for instance determining what’s the next most likely word. The creative freedom of dreaming means you never know what the next word is going to be. At some point, the basic determinism of AI may clash with the basic indeterminism of dreaming. Finally, it could be problematic if the AI-generated images were so vivid that they replaced people’s own internal memories of their dreams, like when you see a photo of a childhood event that shapes and perhaps even takes over your memory of the event. Whatever tools you use for dream interpretation, your own experience of the dream should always remain at the center.

[Note: this post first appeared on Psychology Today’s website on April 30, 2025. The additional text below only appears here.]

I tried each of the available Elsewhere styles with this dream, and here’s what the other ones look like:

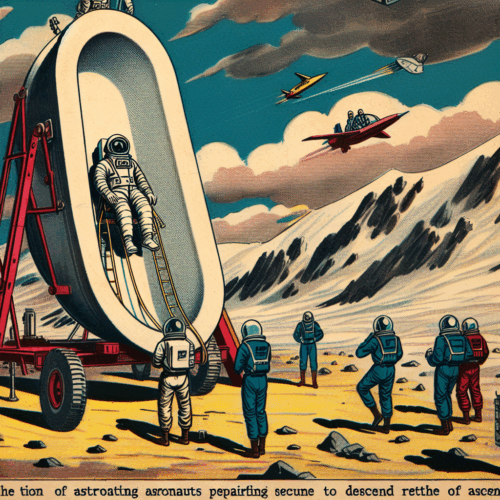

Comic Book:

This one is pretty good–it gives a sense of how the tub is an improbable vehicle for astronauts to travel. There’s no space station, although the up-down dynamics are strong. I find the faux text distracting.

Modern Illustration:

Ouch. It’s white, there’s something like a space station, and something like a tub. But no astronauts, no space, no movement, no weirdness, none of the atmospherics of the dream.

Storybook:

Aesthetically pleasing, and there’s a white tub… And a few stars, if you look closely. Otherwise it has nothing to do with my dream. I do like the celestial feline in the top right.

Woodblock:

This one has a lot going for it. I didn’t expect the Woodcut style to do much with a space scene, but this one is very close to the perspective I felt in the dream, and it’s good on the use of the tub for astronauts traveling down. The space station is disappointingly simple, however, and I don’t like the two-tone coloring.

I’ll close by saying this is a really fun way of playing with a dream and exploring different possible meanings. With the downsides mentioned above still in mind, I look forward to trying this again soon.

It’s hard to beat the simple practice of keeping a dream journal.

It’s hard to beat the simple practice of keeping a dream journal.