“It is in dreams that one can catch sight of the most fundamental and stable symbolisms of humanity passing from the ‘cosmic’ function to the ‘psychic’ function.” (Paul Ricoeur, 1967)

“It is in dreams that one can catch sight of the most fundamental and stable symbolisms of humanity passing from the ‘cosmic’ function to the ‘psychic’ function.” (Paul Ricoeur, 1967)

[The following is the text of a presentation I will make on Saturday, Nov. 17, at the American Academy of Religion annual meeting in Denver, Colorado.]

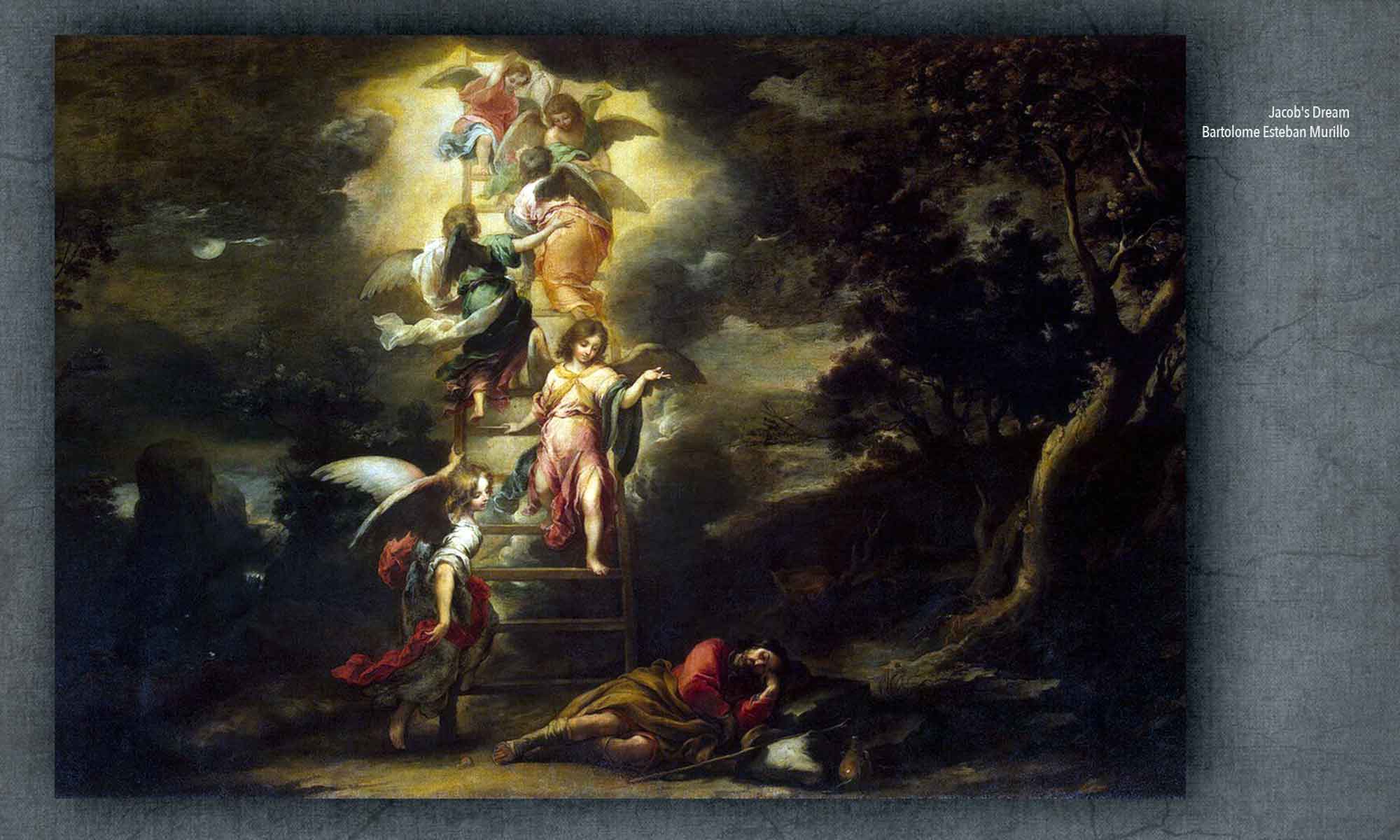

The revelatory power of dreaming, illustrated in the sacred texts and practices of religious traditions all over the world, has naturally led people to actively seek more access to that power. If spontaneous and unexpected dreams can have so much transformational impact, what would happen if one were to prepare for such a dream, and carefully arrange to amplify its impact?

The term “dream incubation” has been used by Western researchers to describe any set of ritual preparations aimed at eliciting a special kind of dream experience (Patton 2004). As Kimberley Patton outlines it, dream incubation involves three elements: locality, intentionality, and epiphany. Dream incubation practices usually involve sleeping in a special place or setting (locality), seeking guidance on a specific question, dilemma, or task (intentionality), and interpreting the resulting dream as a transpersonal response to the dreamer’s intention (epiphany).

Many of the world’s religious and spiritual traditions have ancient practices of dream incubation, defined in these terms. These include the Greek and Roman temples to the healing god Asclepius, where people prayed and slept in hopes of a curative dream; the Vision Quest rituals of the Ojibwa, Iroquois, and other Native American groups, in which an adolescent slept alone in the wilderness for several nights until visited in a special dream by a personal spirit; the Muslim practice of istikhara, with pre-sleep prayers and purifications aimed at eliciting dream guidance on an urgent question; and the Dream Yoga of the Tibetan Buddhist sage Naropa, which teaches methods of preparation for dreaming with greater clarity and consciousness.

In each of these traditions, focused waking attention prior to sleep has the effect of influencing people’s subsequent dreams, which then influence their consciousness upon awakening via interpretation, which then colors their later dreams, on and on in a spiritually dynamic and virtuous cycle (Bulkeley 2008).

Another term widely used by Western scholars, “lucid dreaming,” highlights the powers of self-awareness and volitional control that can arise in dreaming. Such powers have long been recognized and actively cultivated by Hindus, Buddhists, and Daoists, so lucid dreaming is hardly a Western invention. The sages and mystics of those traditions talked about conscious awareness in sleep as a kind of meditative practice that extends beyond the waking state. In indigenous cultures around the world, shamanic healers are trained to become conscious within sleep so they could seek out cures for people who were sick. And many philosophers from classical Greece and Rome admired the potential in sleep for a pure form of mental clarity (although few of them actively explored these possibilities).

The human mind is capable of becoming conscious and active during the state of sleep—that’s the common thread in all these historical traditions. Combining this with the findings of modern psychology and neuroscience—that the mind during sleep can activate the full range of cognitive abilities found in waking (Gackenbach and LaBerge 1988, Kahan and LaBerge 2011)—it becomes clear that lucid dreaming is a natural power of the human mind. Everyone is capable of these revelations in their sleep. Rituals of dream incubation tap into those deep reservoirs of lucid potentiality, and at their best these practices nurture a spiraling interplay of spiritual experience and growth.

With that cross-cultural material setting the stage, I will focus now on a little-known historical example of revelatory dreaming with unusual elements of incubation and lucidity. In this case, the dreamer lived in a community that did not appreciate her visionary insights. On the contrary, she was violently persecuted because of her dreams. This example highlights the potential dangers of revelatory dreaming, dangers that revolve around two key questions:

- How can we tell if a dream is a true revelation, and not just a personal fantasy or total fabrication?

- What is the best/safest/most effective way of channeling the disruptive energies of a revelatory dream?

More than 400 years ago, a young woman with a gift for prophetic dreaming was arrested as a traitor and heretic. Her dreams were judged by the religious authorities to be a danger to the king, the church, and the country as a whole. She was imprisoned, interrogated, tortured, and punished because of her dreams. All of this happened despite the fact that her dreams came true—they accurately predicted a national disaster that could have been avoided if her dreams had been heeded. Instead, she was punished as an enemy of God.

Her name was Lucrecia de Leon. She was born in Madrid in 1568 (making her a contemporary of Shakespeare’s, born in 1564). Madrid was the new capital city of the vast Spanish Empire and its intensely Catholic ruler, King Philip II. She grew up during a time of rapid urban expansion; Madrid had about 10,000 people when she was born and more than 80,000 by the time she was a teenager, with priests, diplomats, and government officials streaming in from all corners of the empire.

Her parents gave her the name Lucrecia, harkening back to the Roman legend of a supremely virtuous young woman of that name (Lucretia) who was raped by prince Tarquin; even though she was blameless, the young woman killed herself to prevent any taint of dishonor from infecting her family’s name. Ever after in Roman and then in Catholic tradition, Lucretia became the ultimate symbol of female honor, chastity, and obedience. We know that Lucrecia de Leon’s father, Alonso, was proud of being an “old Christian,” meaning a Spaniard of pure Christian blood, with no foreign elements tainting his lineage. It seems likely he and his wife Ana chose this name for their firstborn child to emphasize the supreme importance of feminine purity and virtuous behavior.

Alas for Alonso and Ana, their daughter turned out to be a big dreamer. From early in life she gained a reputation in her neighborhood as someone whose dreams frequently came true. In the fall of 1587 a powerful nobleman, Don Alonso de Mendoza, who was interested in apocalyptic omens and symbols, heard about Lucrecia, and he became fascinated by her dreams. Because she was illiterate, he arranged for a priest to come to her house every morning and, in the context of confession, record her dreams from the previous night.

Many of her dreams revolved around Spain’s holy war against England and the Protestant Queen Elizabeth. For years King Philip had been working on a plan to invade England with an attack from the most powerful navy in the world, the Spanish Armada. Philip claimed a holy mandate for the invasion, and the Catholic church helped him whip the Spanish people into a violent frenzy aimed against England.

In this heated, religiously militarized atmosphere, Lucrecia dreamed repeatedly that the Armada would fail. From the fall of 1587 through the summer of 1588, her dreams as recorded by Don Alonso’s priests mentioned the Armada several times, always in negative terms. When the Armada was defeated by the English in the fall of 1588, everyone in Spain was shocked—everyone but Lucrecia.

In the time following this, Lucrecia’s dreams became more widely known, as people looked for new guidance in the aftermath of the Armada’s defeat. This aroused the ire of King Philip, who in the spring of 1590 ordered Lucrecia arrested by the Spanish Inquisition on charges of heresy and treason. She was taken to the Inquisition’s secret prison in the ancient city of Toledo, the spiritual capital of Spain, and held there for five years before a final verdict was rendered in her case.

The main source of evidence against Lucrecia were her dreams, dutifully recorded by Don Alonso’s priests (all of whom were also arrested and imprisoned in Toledo) and then seized by the Inqusition. These dreams are still available for study today in the national historical archive of Spain, in Madrid.

Here is the first one in the surviving manuscripts:

The first of December of this year [1587], the Ordinary Man came to me, and calling me said: “Stick your head out of the window,” which I did, and I heard a great noise and asked him: “What noise is this I hear?” He answered: “You will soon see.” And then I saw coming from the east a cart pulled by two bulls or buffalos (so they said they were called), in which I saw a tower, on the side of which there was a dead lion, and on the top of which was a dead eagle with its breast cut open. The wheels of this cart were stained with blood, and as it moved it killed many people; and many men and women, dressed as Spaniards, were tied to the cart. They were shouting that the world was ending. Not having ever seen anything like this, I asked: “What vision is this?” The Ordinary Man told me that he could not tell me (although he showed signs that he wanted to). In this instant, the Old Fisherman appeared, and I asked him: “Why have you left the seashore and come here?” He responded that it was necessary to come because this man wanted to tell me about this vision, and it should not be known until the third night. I saw that he was carrying a palm leaf, which it seemed he was creating right there. I asked him: “Who is this palm leaf for?” He said: “For the new king who will be to God’s pleasing. I will give it to him, but for the moment I cannot say any more.” And then I woke up…

Lucrecia’s dreams often began in the normal setting of her home, looking out her bedroom window, and then something fantastic and otherworldly would happen—she would journey to a faraway land, or see an amazing sight in the street, or go the palace for an intimate conversation with the king. El Hombre Ordinario (the “Ordinary Man”) was a nearly constant presence in her dreams, and so was El Viejo (the “Old Man”), also known as El Pescador (“the Old Fisherman”). A third figure, known as the “Young Fisherman” or the “Lion Man,” also appeared frequently. These three “companions” usually appeared in a coastal setting, on a beach or cliff overlooking the ocean, hence her surprise in this dream at seeing them in the city rather than at the seashore.

Many other dreams besides this one included strange animals, bloody violence, apocalyptic warnings, and a variety of allegorical symbols. The emotional tone tended toward the negative: fear of the enemies besieging Spain from all directions, and despair at the inability of the king to safeguard his people.

This first report highlights Lucrecia’s general capacity for lucidity and metacognition (that is, high-level mental functioning) during her dream experiences. Almost every one of her dreams included sophisticated thought processes and features of conscious reflection and social intelligence. When she said during her trial testimony, “I wake up the moment my eyes are closed,” she was not just speaking poetically; she was trying to describe the highly conscious quality of her dreaming.

As a result, many of her dreams had at least two levels of activity. At one level she witnessed and/or engaged with elements of the dream world, and at another level she analyzed and interpreted the events occurring on the first level. She often spoke at length with her three companions about the meanings of her ongoing dreams, although the mysterious men rarely gave her a straight answer and often argued among themselves. During these digressive discussions the three companions would occasionally mention Don Alonso, Fray Lucas, and other people in Lucrecia’s waking life, either to correct their mistaken interpretations or comment on their behavior. This added another level of awareness and cognitive complexity to her experiences.

As the dreams went on, night after night, they began to interweave with each other in unpredictable temporal loops, going back to images from previous dreams and looking forward to the appearance of new images in future dreaming.

A core concern here and throughout the series was the fate of the king and the question of who would replace him on the throne (having observed the crown prince up close, Lucrecia apparently had little confidence in the official succession plan). The Old Fisherman’s magically appearing gift of a palm leaf, a common Christian symbol of spiritual victory, made it clear that Philip’s reign must end so a new king “to God’s pleasing” could lead Spain to a better future.

Lucrecia dreamed repeatedly about dangers to Spain, the death of the king, the scheming of Francis Drake and Queen Elizabeth in England, and threats to the Spanish fleet, which was led by the Marquis of Santa Cruz. In a dream from December 14, 1587, Lucrecia saw a terrible vision of war on the sea and woe for the Spanish Armada:

I saw two strong fleets fighting a fierce battle. Because I had seen them fight before, I knew that one was the fleet of the Marquis of Santa Cruz, the other of Drake. This battle was the fiercest and loudest of all those I had seen in other dreams. Previously, I had seen them fighting in a port; this one was on the high seas and lasted all afternoon because before it began I heard a clock strike one; it lasted three hours, until sunset. Once the sun was down, I saw the defeated fleet of the Marquis of Santa Cruz fleeing toward the north, having lost many of its ships and men, and I saw Drake’s fleet returning to England to take on more troops. I saw Drake writing letters, asking for more men. He also wanted to forward a request for troops to the Great Turk, but one of his knights said, “Do not send it, the men we have are enough to secure victory.” And with this I woke up.

Lucrecia had several other ominous dreams in 1587 and 1588 about the Armada’s dire future, which were recorded by Don Alonso’s scribes and shared among various members of the court and nobility. When the Armada was in fact defeated in August of 1588, no one could say they had not been warned. Yet it seemed inconceivable to the religious and political leaders of Spain that the vehicle for this shockingly accurate prophecy was a poor, uneducated young woman. Indeed, her very existence now posed an embarrassing affront to King Philip, who had put so much personal and theological emphasis on the holy cause of the Armada. Finally, he had enough. In May of 1590 he directed his religious police, the Inquisition, to put an end to her prophetic career.

So. What does this story tell us about the two questions I posed at the outset, questions that are relevant to almost every historical and contemporary instance of revelatory dreaming?

First, how can we tell if a dream is a true revelation, and not just a personal fantasy or total fabrication?

The answer is clearly not a trial by the Spanish Inquisition. That much comes through in Lucrecia’s story.

Ironically, the trial did highlight many of the criteria that can be used to reach a more satisfying answer. Indeed, in many ways Lucrecia, Don Alonso, and his colleagues conducted an admirably well-designed research study of precognitive dreaming. Her dreams were recorded as soon as they occurred, by someone other than the dreamer. The significant patterns emerged across many dreams, not just from a single dream. The dreams were recorded many months before the predicted event (the defeat of the Armada) occurred. The dreamer displayed no signs of mental illness or erratic behavior. She gained little personal benefit from sharing her dreams; indeed, she brought tremendous danger upon herself by doing so. And, when all was said and done, her dreams unmistakably came true—they accurately predicted a shocking national disaster.

By these pragmatic criteria, Lucrecia’s dreams can be judged true revelations.

Second, what is the best/safest/most effective way of channeling the disruptive energies of a revelatory dream?

For the few months that it worked as planned, the system Don Alonso set up provided Lucrecia with an amazing opportunity to contribute her oneiric gifts to something bigger than herself. By sharing her dreams with Don Alonso’s scribes each morning, she felt she was actively helping to promote the welfare of her country and her faith. She evidently found this a very meaningful pursuit, and it was during these times that Lucrecia was healthiest, her dreams most vivid, and her relationship with Don Alonso most trusting and mutually respectful. Although the process took a horrific turn, there was a brief period in which a highly effective method emerged, with a group of dedicated people channeling a powerful source of revelatory dreaming towards an issue of immense public concern. The king and his religious police may have rejected the product of this method, but that does not take away from the fact that, had they been heeded, Lucrecia’s dreams could have staved off a catastrophe that cost thousands of Spanish lives.

Let me conclude with the idea that Lucrecia’s abilities as a prophetic dreamer were unusual, but not unique. Other people in various places and times, including people today, have experienced similar phenomena. Perhaps everyone has the potential for such dreams, given the right circumstances. Lucrecia’s dreams highlight latent abilities within the human psyche that are real, powerful, and potentially valuable, although they may appear threatening to traditional religious and political authorities.

This is true today as well. The wild multiplicities of dreaming inevitably run into conflict with rigid, monolithic systems of thought and behavior. At a time when waking-world boundaries are hardening and clashes between ideological tribes are worsening, the act of dreaming, and sharing dreams, becomes a meaningful political and spiritual gesture. Dreams remind us of our existential freedom and capacity for future growth, and they help us see the world from various perspectives besides that of our waking ego. They tap into our deepest sources of creative insight, and, in cases like Lucrecia’s, they envision threats to our communities that can be avoided if consciously recognized and humbly acknowledged.

####

References:

Bulkeley, Kelly. 2018. Lucrecia the Dreamer: Prophecy, Cognitive Science, and the Spanish Inquisition. Stanford University Press.

________. 2008. Dreaming in the World’s Religions: A Comparative History. NYU Press.

Gackenbach, Jayne, and Stephen LaBerge, ed.s. 1988. Conscious Mind, Sleeping Brain: Perspectives on Lucid Dreaming. Plenum.

Kahan, Tracey and Stephen LaBerge. 2011. “Dreaming and Waking: Similarities and Differences Revisited.” Consciousness and Cognition 20: 494-515.

Patton, Kimberley. 2004. “‘A Great and Strange Correction’: Intentionality, Locality, and Epiphany in the Category of Dream Incubation.” History of Religions 43: 194-223.

Ricoeur, Paul. 1967. The Symbolism of Evil. Beacon Press.

Presentation information:

American Academy of Religion Annual Meeting

Denver, Colorado

A17-235

Western Esotericism Unit

“Esoteric Traditions of Revelatory Dreaming”

November 17, 2018, Saturday, 1-3 pm

Convention Center-505

Abstract

The revelatory power of dreaming, illustrated in the sacred texts and practices of religious traditions all over the world, has prompted people in many cultures to seek more access to that power via rituals of dream incubation, which can generate intensified dreams of conscious awareness and metacognition (lucid dreaming). With that comparative material as context, this presentation will focus on the author’s original research on a little-known historical example of revelatory dreaming: Lucrecia de Leon, a young woman from 16th century Spain whose prophetic dreams threatened the king and brought down the wrath of the Inquisition. This example highlights some of the potential dangers of revelatory dreaming, dangers that revolve around two key questions: How can we tell if a dream is a true revelation, and not just a personal fantasy or total fabrication? What is the best/safest/most effective way of channeling the disruptive energies of a revelatory dream?

Dreaming, play, theater, science, religion, social and political crisis.

Dreaming, play, theater, science, religion, social and political crisis.

“It is in dreams that one can catch sight of the most fundamental and stable symbolisms of humanity passing from the ‘cosmic’ function to the ‘psychic’ function.” (Paul Ricoeur, 1967)

“It is in dreams that one can catch sight of the most fundamental and stable symbolisms of humanity passing from the ‘cosmic’ function to the ‘psychic’ function.” (Paul Ricoeur, 1967) The world’s biggest yearly gathering of dream researchers, teachers, artists, and therapists is less than two weeks away.

The world’s biggest yearly gathering of dream researchers, teachers, artists, and therapists is less than two weeks away. On May 25, 1590, by direct order of King Philip II, the Spanish Inquisition arrested a young, uneducated woman from Madrid named Lucrecia de Leon on charges of heresy and treason. She was brought to a secret prison in Toledo, interrogated, and tortured to make her confess her guilt. The evidence against her was overwhelming. She had been caught conspiring with known rebels, publicly slandering the king, defying direct orders from the church, and stirring up dissent against the imperial government.

On May 25, 1590, by direct order of King Philip II, the Spanish Inquisition arrested a young, uneducated woman from Madrid named Lucrecia de Leon on charges of heresy and treason. She was brought to a secret prison in Toledo, interrogated, and tortured to make her confess her guilt. The evidence against her was overwhelming. She had been caught conspiring with known rebels, publicly slandering the king, defying direct orders from the church, and stirring up dissent against the imperial government.