The world’s biggest yearly gathering of dream researchers, teachers, artists, and therapists is less than two weeks away.

The world’s biggest yearly gathering of dream researchers, teachers, artists, and therapists is less than two weeks away.

The 35th annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams (IASD) will be held June 16-20 in Scottsdale, Arizona, USA. I attended my first IASD conference in 1988 in Santa Cruz, California, and I have only missed two since then. This year I am giving several presentations, covering a range of current and emerging interests. The conferences offer an ideal place to share new ideas and test future plans. Many of my projects over the years have been the outgrowth and flowering of seeds first sown at an earlier IASD conference. Below are the seeds I’m planting this year.

June 17-20, 8:00-9:00 am

Morning Dream-Sharing Workshop, with Bernard Welt

“Dream Journaling for First-Time IASD Conference Attendees”

This morning workshop is for first-time IASD attendees, who will learn a variety of methods for starting a dream journal, exploring the dreams that accumulate over time, and discovering surprising potentials for creativity and insight. Attendees will be able to share their experiences and discuss common themes and questions. The initial meeting of the workshop will involve introductions, questions about the conference, a discussion of initial interests in dreams, and a list of topics people want to learn more about. The presenters will take time to introduce the attendees to the basic practice of keeping a dream journal, which some of the attendees may already do. Also discussed in introductory terms will be the role of dream journals in history, art, religion, and science. The following sessions each morning will provide ample space for the attendees to process their experiences at the conference, ask questions, share impressions, and correlate different ideas from different sources. The presenters will make sure in each session to devote at least half the group’s discussion to various practical aspects of dream journaling, and the list of interests and questions that arose from the first session.

Sunday, June 17, 4:15 to 6:15 pm

Arts Symposium: Dreaming, Media, and Consciousness

“The Mythic Roots of Cinematic Dream Journeys”

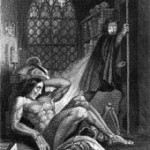

The presentation will start with a discussion of the idea of films as simulated dreams (with “films” also including works appearing on television, some shorter than typical movies, some longer). The presentation will analyze the elements of cinematic experience in terms of its historical roots in theater, myth, religious ritual, and shamanic journeys. The focus in this first section will be the creative interplay of art and dreaming within the formal features of cinematic experience. The second section will focus on two dream-related themes in several films and television shows that have deep mythic roots. One of these themes is the heroic journey into the realm of dreaming in quest for something of importance or value for the waking world. The other theme is the danger of becoming trapped in the realm of dreaming and no longer knowing what is waking and what is dreaming, or who is dreaming whom. These two themes have alternately enchanted and terrified humans throughout history, as witnessed in various myths, stories, and philosophies around the world, and now in the movies and tv shows of the present day. The power, mystery, and wonder-provoking weirdness of dreaming emerges very clearly in several films and televisions shows, including Dead of Night, Dream Corp. LLC, The OA, and Twin Peaks: The Return. These and other works will be considered in terms of the two mythic themes of heroic journey and identity paradox.

Tuesday, June 19, 11:30 to 1:00

Religious Research Panel: Dreams About God

“The Dreams of God of Lucrecia de Leon”

The dreams of God reported by Lucrecia de Leon, a young woman from 16th century Spain, included dangerously accurate prophecies that brought down the wrath of the Inquisition. This presentation explores the religious, psychological, and political dimensions of her dreams, especially the theme of dreams as speaking truth to power (drawing on the historical research I did for Lucrecia the Dreamer: Prophecy, Cognitive Science, and the Spanish Inquisition). The presentation will start with the historical context of Lucrecia and the religious dynamics of her life and community. It will then look at the 24 dream reports specifically mentioning “God” in the main collection of her dreams, and discuss the main themes and features of these dreams. This discussion will include use of digital methods of data analysis, Jungian psychology, cognitive science, and metaphorical theology. The presentation will conclude with reflections on the psychological, political, and religious dimensions of dreaming in historical circumstances and in the present-day.

Wednesday, June 20, 2-3:30 pm

Dreamwork Panel: Theories and Work of Jeremy Taylor

“Creating a Dream Library”

Following his death, Jeremy Taylor’s massive collection of books and papers have been entrusted to me, and in this presentation I will share plans for building a library that will provide a long-term archive for Jeremy’s books and papers, plus my books and papers and other dream-related resources people have shared with me. I will discuss the plans for this library in relation to Jeremy’s tool-kit principle #1 that ALL dreams speak in a universal language of symbol and metaphor. That principle offers a key for understanding the nature and significance of Jeremy’s library (a vast repository of the world’s mythic, religious, and artistic traditions). I will also address Jeremy’s personal practice of dream journaling and its importance for an appreciation of his life and work.

An international group of artists join together to explore their dreams.

An international group of artists join together to explore their dreams. I’ve been thinking a lot recently about a new book,

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about a new book,