Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.

Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.

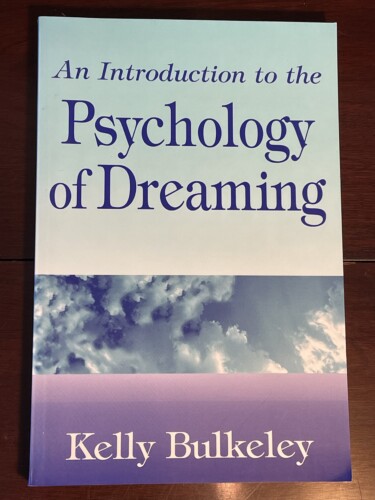

But…there was the secondary text issue. The change of mind and heart came when I recognized the creative opportunities in writing an overview of the history of modern dream psychology. As I looked at other versions of this history, and there were not many, I became increasingly confident that I could write a good, clear, multidisciplinary version of this story, whether or not it amounted to a secondary text. And then, once I got going, it was a very quick writing process. I’d say it took ten years of continuous study to be able to write the book in about three months.

As a way of orienting myself within the tremendous breadth and diversity of the field, and thus being able to explain its contours in clear terms to students new to this subject, I settled on three basic questions that I would ask at each new point in the story:

- How are dreams formed?

- What function or functions do dreams serve?

- Can dreams be interpreted?

These three questions give the book a tight analytic structure that makes it easy to compare similarities and differences among the various theories. To illustrate how the three questions are used going forward, I apply them in the Introduction to the ancient dream teachings found in the Bible, the philosophy of Aristotle, and the Oneirocriticon of Artemidorus. I’m trying to give readers a sense of how many of the ideas and theories of modern dream psychology did not appear out of the blue but have deep roots in the Western cultural tradition.

The order of chapters follows a by-now conventional chronology, starting with the dream theories of Sigmund Freud, then Carl Jung, then branching out into different versions of psychoanalytic psychology with a clinical focus (Alfred Adler, Medford Boss, Thomas French and Erika Fromm, Frederick Perls). Next are chapters about the findings of sleep laboratory researchers like Eugene Aserinsky, Nathaniel Kleitman, and J. Allan Hobson, and experimental psychologists like Jean Piaget, Calvin Hall, David Foulkes, Harry Hunt, and Ernest Hartmann. The last chapter is titled “Popular Psychology: Bringing Dreams to the Masses,” which chronicles the contributions of people who, beginning in the 1960’s and 1970’s, expanded the horizons of dream psychology both in the way they practiced dream interpretation (in group settings, not just in psychiatric sessions or sleep labs) and in the dreamers they included (all people in all cultures, not just Western therapy patients). This chapter profiled the work of Ann Faraday, Patricia Garfield, Gayle Delaney, Jeremy Taylor, Montague Ullman, Stephen LaBerge, and ends with the “Senoi Debate” between Kilton Stewart and G. William Domhoff.

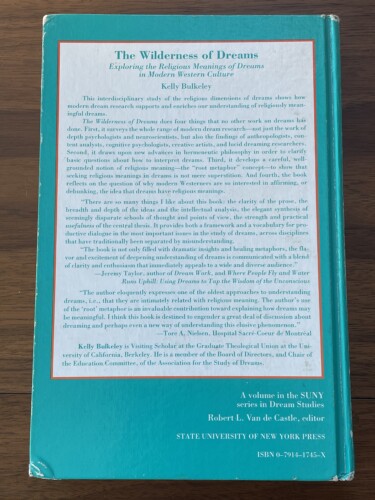

The cover was entirely out of my hands. It’s fine, I’ve come to like the blue-to-indigo colors and the cloudy sky imagery, it’s all rather trippy. We persuaded two eminent sleep laboratory researchers, Ernest Hartmann and Wilse Webb, to write back-cover endorsements. Hartmann and Webb were both in the first generation of psychologists who studied how the new findings about REM and NREM sleep relate to psychoanalytic insights about the nature of dreaming. If they were happy with the book, then mission accomplished.

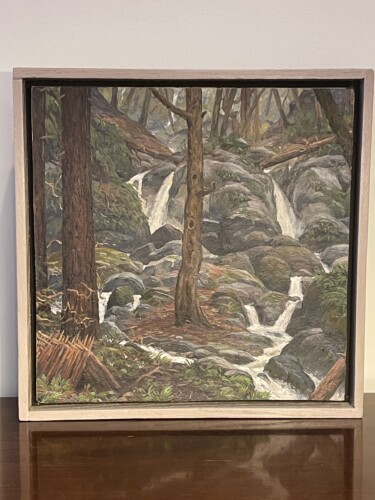

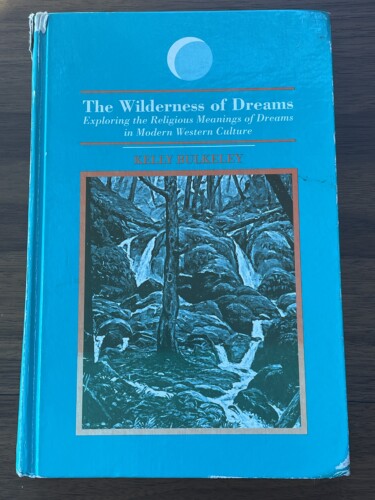

It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend

It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend

In Sigmund Freud’s pioneering book The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), he explained how dreams are formed by referring to four factors that make up what he called the “dream-work.” Even after the passage of more than a century, many of Freud’s key concepts are still valid and useful in the practice of dream interpretation. This includes his observation that four specific factors are central to the construction of dreams. These factors are fairly easy to identify, not only in dreams but in other areas of people’s lives, too. With this claim, Freud dramatically raised the stakes for the science of dreaming—more than just providing knowledge about the sleeping mind, it can also become a source of insight into other arenas of human symbolic behavior and expression.

In Sigmund Freud’s pioneering book The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), he explained how dreams are formed by referring to four factors that make up what he called the “dream-work.” Even after the passage of more than a century, many of Freud’s key concepts are still valid and useful in the practice of dream interpretation. This includes his observation that four specific factors are central to the construction of dreams. These factors are fairly easy to identify, not only in dreams but in other areas of people’s lives, too. With this claim, Freud dramatically raised the stakes for the science of dreaming—more than just providing knowledge about the sleeping mind, it can also become a source of insight into other arenas of human symbolic behavior and expression. Dreaming, play, theater, science, religion, social and political crisis.

Dreaming, play, theater, science, religion, social and political crisis.