Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.

Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.

But…there was the secondary text issue. The change of mind and heart came when I recognized the creative opportunities in writing an overview of the history of modern dream psychology. As I looked at other versions of this history, and there were not many, I became increasingly confident that I could write a good, clear, multidisciplinary version of this story, whether or not it amounted to a secondary text. And then, once I got going, it was a very quick writing process. I’d say it took ten years of continuous study to be able to write the book in about three months.

As a way of orienting myself within the tremendous breadth and diversity of the field, and thus being able to explain its contours in clear terms to students new to this subject, I settled on three basic questions that I would ask at each new point in the story:

- How are dreams formed?

- What function or functions do dreams serve?

- Can dreams be interpreted?

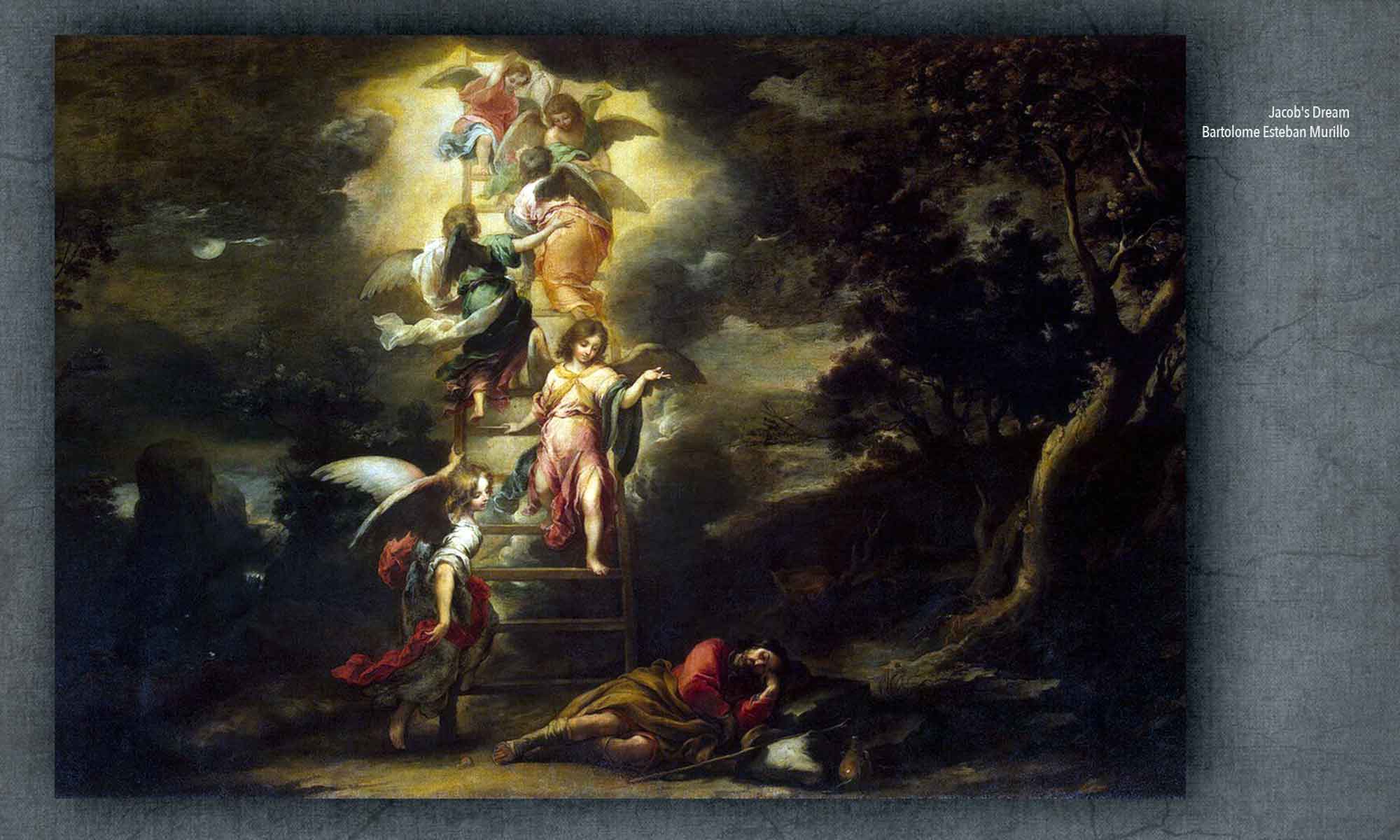

These three questions give the book a tight analytic structure that makes it easy to compare similarities and differences among the various theories. To illustrate how the three questions are used going forward, I apply them in the Introduction to the ancient dream teachings found in the Bible, the philosophy of Aristotle, and the Oneirocriticon of Artemidorus. I’m trying to give readers a sense of how many of the ideas and theories of modern dream psychology did not appear out of the blue but have deep roots in the Western cultural tradition.

The order of chapters follows a by-now conventional chronology, starting with the dream theories of Sigmund Freud, then Carl Jung, then branching out into different versions of psychoanalytic psychology with a clinical focus (Alfred Adler, Medford Boss, Thomas French and Erika Fromm, Frederick Perls). Next are chapters about the findings of sleep laboratory researchers like Eugene Aserinsky, Nathaniel Kleitman, and J. Allan Hobson, and experimental psychologists like Jean Piaget, Calvin Hall, David Foulkes, Harry Hunt, and Ernest Hartmann. The last chapter is titled “Popular Psychology: Bringing Dreams to the Masses,” which chronicles the contributions of people who, beginning in the 1960’s and 1970’s, expanded the horizons of dream psychology both in the way they practiced dream interpretation (in group settings, not just in psychiatric sessions or sleep labs) and in the dreamers they included (all people in all cultures, not just Western therapy patients). This chapter profiled the work of Ann Faraday, Patricia Garfield, Gayle Delaney, Jeremy Taylor, Montague Ullman, Stephen LaBerge, and ends with the “Senoi Debate” between Kilton Stewart and G. William Domhoff.

The cover was entirely out of my hands. It’s fine, I’ve come to like the blue-to-indigo colors and the cloudy sky imagery, it’s all rather trippy. We persuaded two eminent sleep laboratory researchers, Ernest Hartmann and Wilse Webb, to write back-cover endorsements. Hartmann and Webb were both in the first generation of psychologists who studied how the new findings about REM and NREM sleep relate to psychoanalytic insights about the nature of dreaming. If they were happy with the book, then mission accomplished.

The image-generating power of new AI systems has huge untapped potential for the practice of dream interpretation—and some potential downsides. Even more than AI interpretive texts, the dramatic power of AI interpretive images may open new vistas for exploring the meanings of dreams.

The image-generating power of new AI systems has huge untapped potential for the practice of dream interpretation—and some potential downsides. Even more than AI interpretive texts, the dramatic power of AI interpretive images may open new vistas for exploring the meanings of dreams.

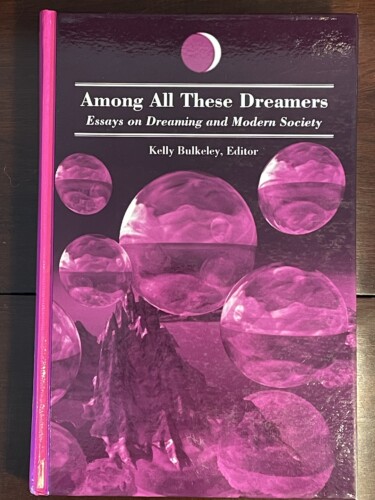

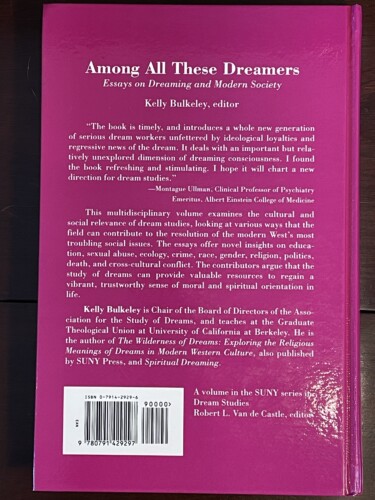

The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

Written by Dan Kennedy of the Elsewhere.to team, this is a very thoughtful survey and evaluation of current apps available for recording and analyzing your dreams.

Written by Dan Kennedy of the Elsewhere.to team, this is a very thoughtful survey and evaluation of current apps available for recording and analyzing your dreams. An academic dissertation is written in compliance with a host of official requirements designed to focus the project and give it the best chance of successful completion. Those requirements definitely influenced how my dissertation and first book, The Wilderness of Dreams (1994), came to be what it is. As I sat down to write my second book, I remember a moment of almost dizzy uncertainty about taking the first steps forward. I knew even before finishing WD that I wanted to write a book about the religious and spiritual aspects of dreaming through history. The first chapter of my dissertation offered a survey of that material, but I had accumulated a larger store of references, much more than could be presented in a single chapter. A book-length study seemed worthwhile, but what exactly would it look like?

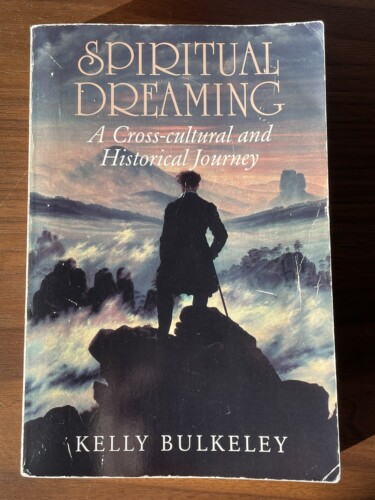

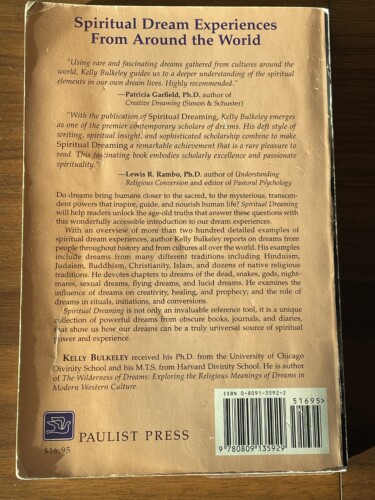

An academic dissertation is written in compliance with a host of official requirements designed to focus the project and give it the best chance of successful completion. Those requirements definitely influenced how my dissertation and first book, The Wilderness of Dreams (1994), came to be what it is. As I sat down to write my second book, I remember a moment of almost dizzy uncertainty about taking the first steps forward. I knew even before finishing WD that I wanted to write a book about the religious and spiritual aspects of dreaming through history. The first chapter of my dissertation offered a survey of that material, but I had accumulated a larger store of references, much more than could be presented in a single chapter. A book-length study seemed worthwhile, but what exactly would it look like? My friend and mentor Jeremy Taylor had published Dream Work (1983) with Paulist Press and spoke highly of their editor, Lawrence Boadt. That’s how I came to make an arrangement with Paulist to publish Spiritual Dreaming, with back-cover endorsements from Patricia Garfield and Lewis Rambo. Patricia was a co-founder of the IASD and author of several well-regarded books on dreams, and Lewis was a professor of religion and psychology at San Francisco Theological Seminary and my faculty sponsor at the Graduate Theological Union, where I had become a Visiting Scholar after leaving Chicago.

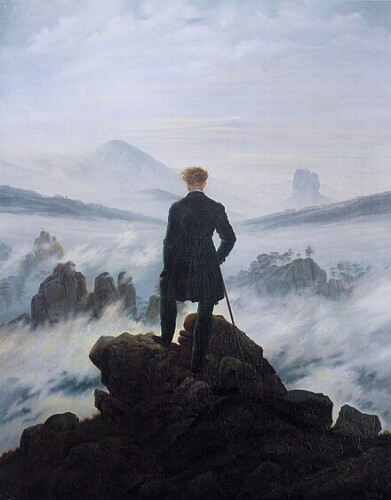

My friend and mentor Jeremy Taylor had published Dream Work (1983) with Paulist Press and spoke highly of their editor, Lawrence Boadt. That’s how I came to make an arrangement with Paulist to publish Spiritual Dreaming, with back-cover endorsements from Patricia Garfield and Lewis Rambo. Patricia was a co-founder of the IASD and author of several well-regarded books on dreams, and Lewis was a professor of religion and psychology at San Francisco Theological Seminary and my faculty sponsor at the Graduate Theological Union, where I had become a Visiting Scholar after leaving Chicago. The front cover is a painting from Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog (1818), a classic of early Romantic aesthetics, although I didn’t know that at the time—I just liked the way this image balanced the cover of WD, which was set deep inside a Redwood-lined creek; here with SD, we’re reaching the top of the ridge and discovering a big open view to enjoy.

The front cover is a painting from Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog (1818), a classic of early Romantic aesthetics, although I didn’t know that at the time—I just liked the way this image balanced the cover of WD, which was set deep inside a Redwood-lined creek; here with SD, we’re reaching the top of the ridge and discovering a big open view to enjoy.