The past one hundred years of human history have been dramatically transformed by the invention of several new technologies, each of which has impacted people’s lives in profound and complicated ways.

The past one hundred years of human history have been dramatically transformed by the invention of several new technologies, each of which has impacted people’s lives in profound and complicated ways.

In light of empirical research showing strong continuities between waking and dreaming, we can hypothesize that modern technologies have also made a tangible impact on the content of people’s dreams.

And indeed, there is evidence in support of that idea. By analyzing a collection of more than 16,000 dream reports available for study on the Sleep and Dream Database (SDDb), it becomes possible to examine which kinds of technology have most influenced people’s dreams in terms of their frequency of appearance.

The results suggest the newest technologies are not necessarily the most important ones in the world of dreams.

To explore this question I looked at all the dream reports on the SDDb of 25 words or more in length for Females (N=10,168) and Males (N=6,590), and selected the “Technology and Science” category from the 2.0 word search template.

This is a quick and dirty approach, but it has the virtue of providing an easy and relatively straightforward means of getting an evidence-based response to the question.

The results for the Females were 990 dream reports with at least one reference to a word in the “Technology and Science” category, approximately 10% of the total number of dreams. The figures for the Males were 602 and 9%.

Looking in more detail at which terms appeared most frequently (these include singular and plural uses of the term), the results for the Females were these:

Phone, 3.55%

Movie, 3.18%

Video, 1.26%

Computer, 1.2%

Machine, .91%

Radio, .65%

Camera, .62%

Television, .26%

And for the Males:

Phone, 2.69%

Movie, 2.47%

Video, 1.27%

Computer, 1.03%

Machine, 1.02%

Radio, .47%

Camera, .49%

Television, .36%

I did a parallel search with the same two sets using the SDDb 2.0 word search template category for Transportation. These results—24% of the dream reports for both Females and Males had at least one reference to a Transportation word—are much higher than the Technology and Science frequencies.

Looking more closely at specific forms of transportation appearing in people’s dreams, these were the results for the Females:

Car, 9.12%

Boat, 1.92%

Bus, 1.81%

Airplane, 1.49%

Truck, 1.26%

Elevator, 1.16%

Bicycle, .86%

And for the Males:

Car, 8.18%

Boat, 2.12%

Bus, 1.65%

Bicycle, 1.56%

Airplane, 1.46%

Truck, 1.37%

Elevator, .67%

The first thing to note is the remarkable gender balance. On almost all the categories and word clusters, the Female and Male frequencies are extremely close. (The main exceptions are slightly more Bicycle references for the Males, and slightly more Phone, Movie, Car, and Elevator references for the Females.) This consistency across so many terms suggests that modern technologies have impacted men and women about equally.

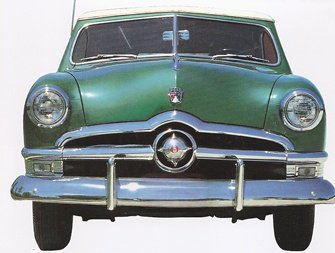

Secondly, the analysis indicates that the most frequently appearing modern invention in dreams is the automobile. It seems that technologies of transportation have had more of an impact on people’s dreams than have technologies of communications and entertainment. Add in trucks and buses to cars, and the predominance of the internal combustion engine in dreaming becomes even greater.

Why might this be? I’m not sure, but I wonder if technologies of transportation have more of a visceral impact on people’s lives. Telephones, movies, videos, and computers can be fascinating and absorbing, but they do not directly affect a person’s body with the kind of sensory intensity that people feel during a car ride.

Whatever the explanation, the results of this brief study indicate that the most frequently appearing type of modern technology in dreams is one that was invented more than one hundred years ago. Newer technologies like computers and videos have not (yet) made as big an impression on the dreaming imagination.

Maybe future developments in virtual reality will enable a more powerful stimulation of people’s physiological responses, prompting a rise in VR-related dreams. But that remains a far-off possibility.

Until then, cars remain for most people the dream technology of choice.

Note: here are the word strings for the specific technology and transportation searches:

Phone: phone phones telephone telephones iphone iphones. Video: video videos. Computer: computer computers. Machine: machine machines machinery. Radio: radio radios. Camera: camera cameras. Television: television televisions tv tvs.

Car: car cars auto autos automobile automobiles. Boat: boat boats ship ships. Bus: bus buses. Bicycle: bicycle bicycles bike bikes. Airplane: airplane airplanes plane planes. Truck: truck trucks. Elevator: elevator elevators.