The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

The first time I attended an annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams was in Santa Cruz in 1988. For the next several years (London in 1989, Chicago in 1990 (which I hosted), Charlottesville, Virginia in 1991) these conferences gave me an opportunity to learn more about the various ways in which people were exploring the origins, functions, and meanings of dreaming. One thing that struck me right away was that several people were looking at dreams not only as a source of personal insight but also as a source of insight into collective issues and concerns. Based on my own studies so far, this seemed like an important idea for dream researchers to develop further, even if it ran counter to the predominantly individualistic approach of most psychologists at that time.

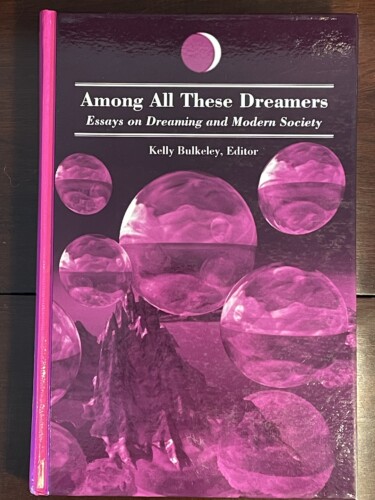

Inspired by these colleagues at the IASD, I put together an edited book, Among All These Dreamers: Essays on Dreaming and Modern Society, which was published in 1996 by State University of New York (SUNY) Press as part of the Series in Dream Studies edited by Robert Van de Castle. Each of the chapters is a written version of material presented at an IASD conference and shaped by those conversations. Here are the chapter titles:

- Dreams and Social Responsibility: Teaching a Dream Course in the Inner-City –Jane White-Lewis

- The 55-Year Secret: Using Nightmares to Facilitate Psychotherapy in a Case of Childhood Sexual Abuse – Marion A. Cuddy & Kathryn E. Belicki

- Seeking the Balance: Do Dreams Have a Role in Natural Resource Management? – Herbert W. Schroeder

- Reflections on Dreamwork with Central Alberta Cree: An Essay on an Unlikely Social Action Vehicle – Jayne Gackenbach

- Black Dreamers in the United States – Anthony Shafton

- Sex, Gender, and Dreams: From Polarity to Plurality – Carol Schreier Rupprecht

- Traversing the Living Labyrinth: Dreams and Dream-Work in the Psychospiritual Dilemma of the Postmodern World – Jeremy Taylor

- Invitation at the Threshold: Pre-Death Spiritual Experiences – Patricia Bulkley

- Western Dreams about Eastern Dreams – Wendy Doniger

- Political Dreaming: Dreams of the 1992 Presidential Election – Kelly Bulkeley

- Healing Crimes: Dreaming Up the Solution to the Criminal Justice Mess – Bette Ehlert

- Let’s Stand Up, Regain Our Balance, and Look Around at the World – Johanna King

The conclusion presents what I consider a “Soc. 2 Manifesto,” drawing upon ideas developed during the teaching I did at the University of Chicago from 1989 to 1993 in the yearlong Social Sciences core sequence titled Self, Culture, and Society (Soc. 121-121-123), commonly known as Soc. 2. Max Weber’s notion of the disenchantment of the modern world is a central notion here, which I believe casts a new and more urgent light on the cultural value of dreaming and its innately spiritual qualities.

The title came to me in a flash. One day while working on the book I thought, maybe I could use a phrase from Nietzsche. I stood up, took The Gay Science from my bookshelf, flipped it open, and almost immediately landed on Aphorism 54 and the following paragraph:

“Appearance for me is that which lives and is effective and goes so far in its self-mockery that it make me feel that this is appearance and will-o’-the-wisp and a dance of spirits and nothing more—that among all these dreamers I, too, who ‘know,’ am dancing my dance; that the knower is a means for prolonging the earthly dance and thus belongs to the masters of ceremony of existence; and that the sublime consistency and interrelatedness of all knowledge perhaps is and will be the highest means to preserve the universality of dreaming and the mutual comprehension of all and thus also the continuation of the dream.” (translation by Walter Kaufman, emphasis in original)

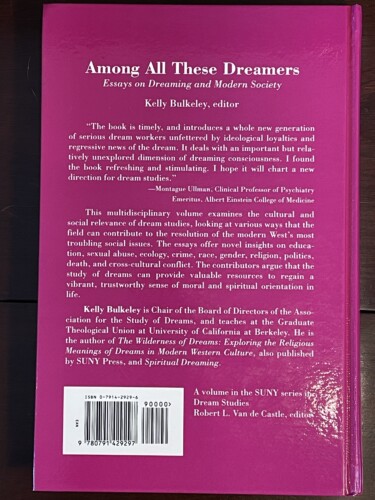

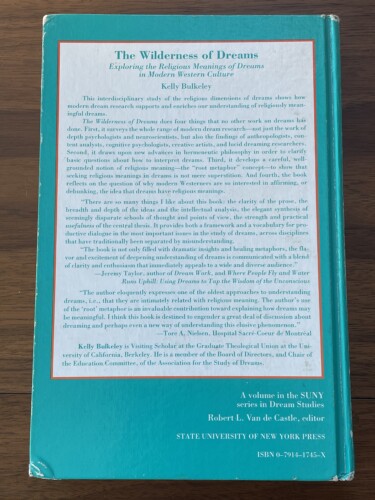

The book’s cover was not my design, although I’m okay with the trippy interplanetary image and vibrant magenta color. The SUNY Series in Dream Studies had a house style they wanted each new book to use, and that’s what we did here. The back cover endorsement from Montague Ullman was especially appreciated since he is one the true pioneers in the application of dream interpretation methods to group programs for community mental health.

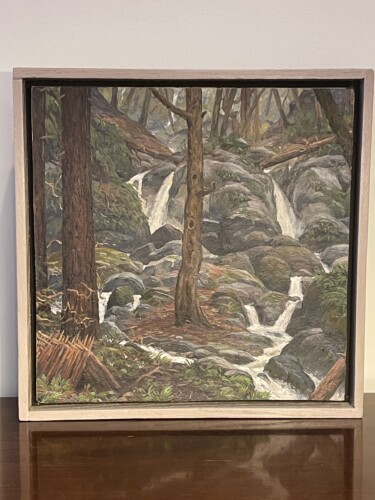

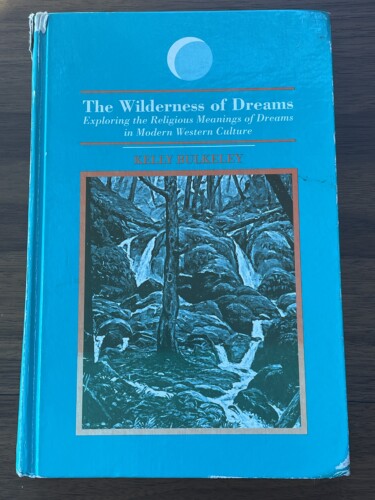

It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend

It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend

Construction is going well so far on the Dream Library, a stand-alone structure on a rural, forested property near Portland, Oregon. As many friends and colleagues know, the project has taken a long time to reach this stage, but at last it’s beginning to take actual shape. The building will provide a long-term archive for dream-related materials such as journals, books, and art. The journal & book collections of Jeremy Taylor and Patricia Garfield will form the core of the library, along with other donated materials and my own collections.

Construction is going well so far on the Dream Library, a stand-alone structure on a rural, forested property near Portland, Oregon. As many friends and colleagues know, the project has taken a long time to reach this stage, but at last it’s beginning to take actual shape. The building will provide a long-term archive for dream-related materials such as journals, books, and art. The journal & book collections of Jeremy Taylor and Patricia Garfield will form the core of the library, along with other donated materials and my own collections.

Here are the recent posts I have written for Psychology Today, going back to the middle of last summer. Although each one is written as a stand-alone discussion of a special topic in dreaming, I now realize they also form a series of interrelated texts, like the chapters of a book I didn’t consciously know I was writing….

Here are the recent posts I have written for Psychology Today, going back to the middle of last summer. Although each one is written as a stand-alone discussion of a special topic in dreaming, I now realize they also form a series of interrelated texts, like the chapters of a book I didn’t consciously know I was writing…. Simple steps you can take to help the future study of dreams.

Simple steps you can take to help the future study of dreams.