Enlightenment philosophers helped to spark the scientific revolution, but they were not always accurate or justified in their assumptions about dreaming.

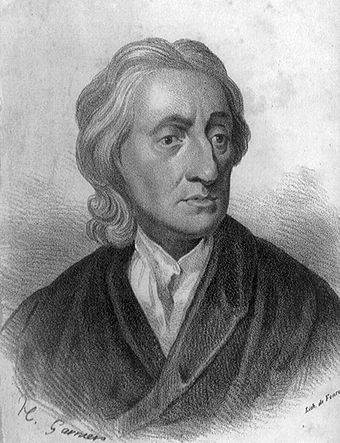

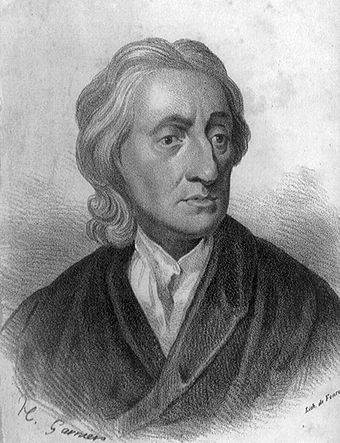

The English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) played a vital role in promoting the ideals of the Enlightenment throughout Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These ideals included a trust in human reason, a corresponding distrust in authority and received opinion, and a demand that people who make theoretical claims about nature, society, the mind, etc., must offer empirical evidence to back up their assertions.

The English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) played a vital role in promoting the ideals of the Enlightenment throughout Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These ideals included a trust in human reason, a corresponding distrust in authority and received opinion, and a demand that people who make theoretical claims about nature, society, the mind, etc., must offer empirical evidence to back up their assertions.

These powerful principles of the Enlightenment set the stage for the scientific and technological revolutions that have changed the world over the past few hundred years. The digital technologies we use and enjoy today have emerged directly out of this cultural lineage reaching back to Locke and his contemporaries. Unfortunately, many Enlightenment philosophers made false and misguided claims about dreaming that have also shaped the lineage of our digital world. If we want to create a healthy ecosystem for technologically enhanced dream exploration, we have to make sure we accept and trust the philosophical assumptions built into that ecosystem.

In his greatest work, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (first published in 1690), Locke explains how the mind works and the process by which humans gain true knowledge about the world and themselves. Early in the book he delves into the topic of sleep and dreaming, because he recognizes that the functioning of the mind while awake is quite different from the functioning of the mind while asleep. Locke is here confronting a key question that many philosophers before and after him have tried to answer: how does mental activity during sleep relate to mental activity while awake?

Unfortunately, Locke makes two false assumptions about human dreaming experience right at the outset, false in Locke’s own sense of being contradicted by empirical evidence. These assumptions allow Locke to make several other claims that do not square with actual scientific research on sleep and dreaming. I will address those further claims in a later post; here, I want to focus on the first two missteps, to see as clearly as possible where Locke initially goes astray.

The first comes in Book II, chapter 1, section 14, when Locke is discussing the nature of ideas and the issue of whether people can dream without remembering it. In this section he asserts, “Most men, I think, pass a great part of their sleep without dreaming.” He then mentions a scholarly friend who never dreamed until he was in his mid-twenties, after a fever. Locke goes on to say, “I suppose the world affords more such instances: at least everyone’s acquaintance will furnish him with examples enough of such, as pass most of their nights without dreaming.”

The empirical reality is more complex than Locke suggests. Modern sleep laboratory research flatly contradicts his claim. If someone sleeping in a laboratory is awakened at certain points in the sleep cycle, the chances are extremely high that the person will recall some kind of dreaming content. Research on “non-dreamers” by James Pagel has shown the proportion of such people appears to be very unusual in the general population. Dozens of studies have shown high levels of regular dream recall people from all demographic groups, all across the social and cultural spectrum.

Locke is right that many people rarely remember their dreams. But he is wrong to suggest that such people are somehow typical or normal, and he makes a major mistake in dismissing from his philosophical theory the mental activities of other people who do remember their dreams frequently.

It might seem unfair to judge Locke’s 17th century claims using 20th and 21st century research. But he did mention, as evidence for his claim, the experience of one of his friends, which means he did at least this much investigation on his own. Did he ever talk with anyone else about their sleep and dream experiences? Did his circle of acquaintances include anyone who was a vivid dreamer? Apparently not, because Locke offered no other empirical support for his assertion than this one friend. That strikes me as a weak foundation for building a larger argument about the nature of the mind.

The second assumption comes in section 16 of the same chapter, in which Locke describes the rational workings of the soul, which he insists occur only in the waking state:

“‘Tis true, we have sometimes instances of perception, whilst we are asleep, and retain the memory of those thoughts; but how extravagant and incoherent for the most part they are; how little conformable to the perfection and order of a rational being, those who are acquainted with dreams, need not be told.”

Locke offers nothing to support this claim; he suggests it is self-evidently true to anyone who is “acquainted” with dreams. The assumption that dreams are characterized by rampant bizarreness continues into the present day, despite there now being several decades of solid empirical research showing that most dreams are, in fact, rather mundane and non-bizarre. Most dreams, it turns out, revolve around familiar people, familiar places, and familiar activities. Many dreams are indistinguishable from people’s descriptions of ordinary events in waking life. Of course there are strange and outlandish things happening in dreams, too, but research on dream content shows that such bizarre elements are not a pervasive and overwhelming quality of dreaming as such.

Again, Locke could have gained this insight if he had taken the time to talk with a few different people about their actual dream experiences. It would not have been difficult for him to reach the empirical conclusion that dreaming includes a mix of both bizarre and non-bizarre elements. But Locke evidently felt his philosophical ideas required him to mute or eliminate entirely the possibility of significant mental activity in sleep, and so he did his best to discourage any further attention to this realm of the mind.

The irony is that this topic of bizarreness is actually an excellent example of where dream researchers have put Locke’s principles into practice, to wonderfully liberating effect. Empirical studies of thousands of dream reports, using careful and systematic methods of analysis, have produced results that have overturned an authoritative but irrational assumption, transforming a false opinion into true knowledge. Locke’s powerful method is an excellent means of refuting Locke’s weak assumptions.

####

Note: all the references to research findings are cited in Big Dreams: The Science of Dreaming and the Origins of Religion (Oxford University Press, 2016).

The bizarre contents of dreaming can easily seem like the products of mental deficiency. “Children of an idle brain” is what Mercutio calls them in Romeo & Juliet (I.iv.102). Many scientists today essentially agree with Mercutio that the weird absurdities of dreams are evidence of diminished cognitive functioning during sleep.

The bizarre contents of dreaming can easily seem like the products of mental deficiency. “Children of an idle brain” is what Mercutio calls them in Romeo & Juliet (I.iv.102). Many scientists today essentially agree with Mercutio that the weird absurdities of dreams are evidence of diminished cognitive functioning during sleep.

The English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) played a vital role in promoting the ideals of the Enlightenment throughout Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These ideals included a trust in human reason, a corresponding distrust in authority and received opinion, and a demand that people who make theoretical claims about nature, society, the mind, etc., must offer empirical evidence to back up their assertions.

The English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) played a vital role in promoting the ideals of the Enlightenment throughout Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These ideals included a trust in human reason, a corresponding distrust in authority and received opinion, and a demand that people who make theoretical claims about nature, society, the mind, etc., must offer empirical evidence to back up their assertions.