As both a dreamer and a researcher, I find myself completely enchanted by the Elsewhere.to dream journaling app. Amazed. Smitten. Blown away. Impressed beyond all reckoning. And very excited about the future for dreamers all around the world.

As both a dreamer and a researcher, I find myself completely enchanted by the Elsewhere.to dream journaling app. Amazed. Smitten. Blown away. Impressed beyond all reckoning. And very excited about the future for dreamers all around the world.

For the longest time, I wondered what it would take to create a dreamer’s playground: a private, safe, fun place to gather your dreams and freely explore them using a variety of high-quality tools and methods. It always seemed like an impossible fantasy… And now, Elsewhere has made that vision a reality by creating a garden of oneiric delights where you can play with your dreams, celebrate their multiplicities of meaning, and follow your curiosity wherever it leads.

The Ethics of Online Dream Interpretation

Anything that has great potential for good also has great potential for harm. I would not be involved with Elsewhere were it not for its total commitment to an ethically minded approach, which I translate as simply doing your best to respect the dream and the dreamer. Treat the dream and the dreamer as ends, not means, as gifts to be honored rather than resources to be exploited. That’s the spirit that animates every aspect of the app’s design, from the back-end coding to the front-end user interface.

In practice, this underlies the policy that all information entered by Elsewhere users is privacy protected and will never be sold to a third-party. If for any reason you want your dreams back, you can have them, and all records of them will be removed from the app.

None of the tools or features within Elsewhere will tell you in a single, definitive way what your dreams mean. Instead, you are offered a variety of suggestions and possibilities from multiple perspectives. Hopefully some of these interpretations will lead to helpful insights, but the ultimate authority is always held by you, the dreamer. Only the dreamer knows for sure what their dream means.

New Features

Elsewhere is now available in more than 30 languages, which means these tools are potentially accessible to more than 99% of the human population. This bodes well for the future spread of dream awareness and education all around the world.

The primary function of the app, beyond recording and storing your dreams, is offering you a variety of tools to analyze their contents. These tools include ways to track the appearance of recurrent characters (e.g., parents, friends, celebrities), places (e.g., a beach, classroom, family home), and symbols (e.g., water, gun, mirror).

By recording your dreams on a regular basis, you build up an awareness of psychological rhythms that you may never have noticed within yourself before. You may also notice in reflecting on a long series of dreams that you can distinguish your unusual, highly memorable “big dreams” even more clearly, now that you have a better sense of the basic patterns underlying all your dreaming.

Elsewhere users have become very creative in combining different features to enhance their dream journaling practice. In the past two years, the resources of artificial intelligence (AI) have been built into the app, providing what I now find are its two most stimulating features:

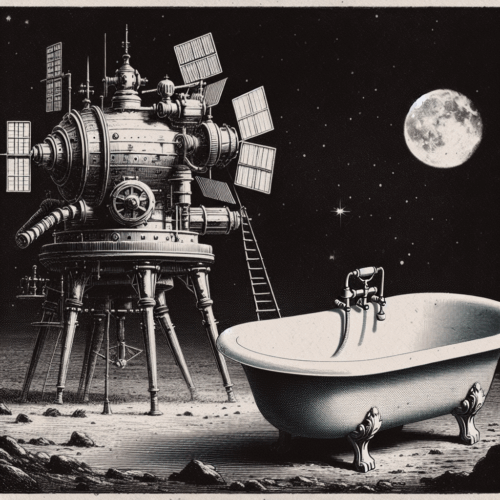

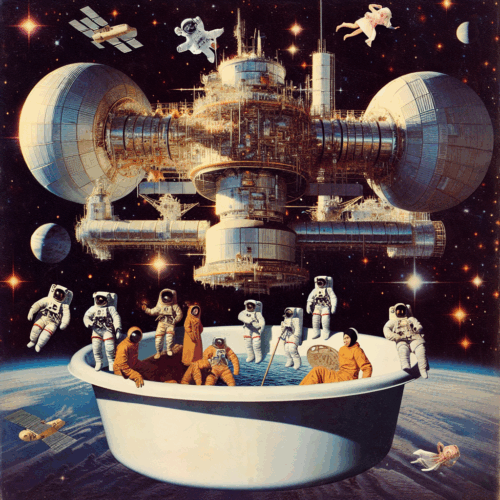

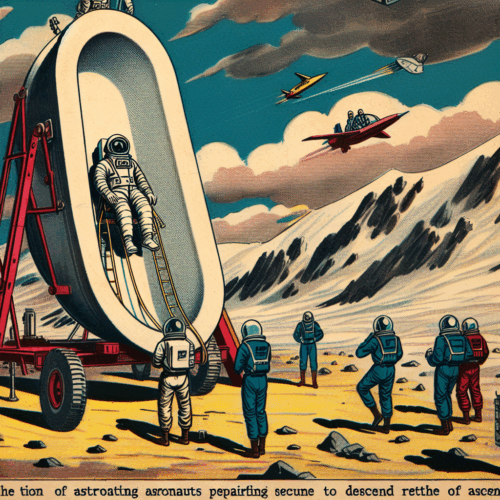

- AI image generation: Elsewhere will create AI-generated images based on your dream and rendered in your chosen aesthetic style: Woodblock, Surreal Collage, Retro Camera, Storybook, Comic Book, Modern Illustration, Old Illustration, along with the option to write your own prompt. For me, this is the tool that yields the most surprising and intriguing results. The images are sometimes bizarrely different from my dreams, but even weird images can be thought-provoking if I look more closely at the image, not for what is missing but rather for what has been enhanced and highlighted beyond what I first noticed in the dream.

- AI interpretations: Elsewhere also offers AI-generated interpretations of dreams in several different modes: Freudian, Jungian, Gestalt, Biblical, relational, spiritual, Lacanian, and the Elsewhere house mode, “Shadow.” These interpretations do not substitute for sharing dreams with other people, but they can provide multiple perspectives quickly and easily, giving the dreamer valuable input to consider while reflecting on their dream. Some of the interpretations are obvious, and others are completely off-base, but here, too, I am frequently surprised by the system offering ideas and viewpoints I have not considered and appreciate being brought to my awareness.

Natural Therapy

The phrase “natural therapy” comes from Robert Kegan’s classic work of developmental psychology, The Evolving Self (1982). In the final chapter of this book, Kegan talks about the simple, non-specialized resources in ordinary life that support our psychological welfare, resources he believes have naturally therapeutic effects even if they are not administered by mental health professionals. He urges us to study these resources more closely:

“Rather than make the practice of psychotherapy the touchstone for all considerations of help, look first into the meaning and makeup of those instances of unselfconscious ‘therapy’ as these occur again and again in nature…[and seek] an understanding of ‘natural therapy’–those relations and human contexts which spontaneously support people through the sometimes difficult process of growth and change.” (256)

Although Kegan does not directly mention dreams in this chapter, I believe that dreaming and dream-sharing have these exact qualities and benefits. There is a tremendous amount of evidence from history and anthropology supporting the connection between dreams and healing. This connection is natural in the sense of being universally accessible and emerging without conscious intention, and yet it is also culturally amplified in responding creatively to the shared symbolic world of the dreamer’s waking reality.

Now, with the help of the powerful tools available in Elsewhere, more people can explore this resource in greater depth than ever before. This will hopefully be of special value to people who may not need formal psychotherapy but can still benefit from gaining more awareness and insight into their unconscious fears, conflicts, and desires.

To be clear, if you need for help from a mental health professional, you should seek it out right away. As a matter of policy, Elsewhere explicitly says it does not claim to provide the services of a psychotherapist. However, in line with Kegan’s thinking, I suggest that Elsewhere does contribute to a form of “natural therapy” by supporting and enhancing people’s access to the beneficial powers of their own dreams. As these potentials begin to emerge into realities, it is worth remembering that dreaming has huge advantages for promoting the collective mental health of large communities insofar as it is free, accessible to everyone, and highly personalized in its relevance to the lived experiences of each individual.

####

Here is an introductory post I wrote about Elsewhere two years ago:

The image-generating power of new AI systems has huge untapped potential for the practice of dream interpretation—and some potential downsides. Even more than AI interpretive texts, the dramatic power of AI interpretive images may open new vistas for exploring the meanings of dreams.

The image-generating power of new AI systems has huge untapped potential for the practice of dream interpretation—and some potential downsides. Even more than AI interpretive texts, the dramatic power of AI interpretive images may open new vistas for exploring the meanings of dreams.

This is a post I recently wrote about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in the practice of dream interpretation. In coordination with the team at the Elsewhere.to dream journaling app–Dan Kennedy, Gez Quinn, and Sheldon Juncker–we have been experimenting with “Freudian” and “Jungian” modes of interpretation, and the results are very encouraging. Maybe more than encouraging… I don’t highlight this in the post, but the AI interpretation in “Jungian” mode used the phrase “confrontation with the unconscious,” which was not part of the prompting text for the AI. In other words, the AI seems to have identified this phrase as a vital one in Jungian psychology (it’s the title of the pivotal chapter 6 of his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections) and, without any direct guidance, used it accurately and appropriately in an interpretation . I might even suspect a sly irony in using this phrase in reference to a dream of Freud’s, but that might be too much…

This is a post I recently wrote about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in the practice of dream interpretation. In coordination with the team at the Elsewhere.to dream journaling app–Dan Kennedy, Gez Quinn, and Sheldon Juncker–we have been experimenting with “Freudian” and “Jungian” modes of interpretation, and the results are very encouraging. Maybe more than encouraging… I don’t highlight this in the post, but the AI interpretation in “Jungian” mode used the phrase “confrontation with the unconscious,” which was not part of the prompting text for the AI. In other words, the AI seems to have identified this phrase as a vital one in Jungian psychology (it’s the title of the pivotal chapter 6 of his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections) and, without any direct guidance, used it accurately and appropriately in an interpretation . I might even suspect a sly irony in using this phrase in reference to a dream of Freud’s, but that might be too much…