Ben Carson, the retired neurosurgeon and leading Republican contender for the Presidency, says that his life was changed by a shadowy figure who appeared in a dream and gave him special advice at a time of crisis. Not since Barack Obama’s 2004 memoir Dreams From My Father has a presidential candidate shared such valuable insight into his personal dreaming experience.

Ben Carson, the retired neurosurgeon and leading Republican contender for the Presidency, says that his life was changed by a shadowy figure who appeared in a dream and gave him special advice at a time of crisis. Not since Barack Obama’s 2004 memoir Dreams From My Father has a presidential candidate shared such valuable insight into his personal dreaming experience.

Carson’s 2009 autobiography Gifted Hands describes a pivotal moment during college when he was threatened with paralyzing doubt about his ability to reach the ambitious goal he had set himself, to become a doctor. Having escaped a dysfunctional family and a poor, crime-ridden neighborhood, Carson was a freshman at Yale University in the pre-med program. He felt overwhelmed by the difficulty of his classes and the competitive pressures from all the other super-bright, hyper-achieving students. Chemistry became a serious problem, and as the end of first semester approached Carson realized he was very likely to fail the class. That would knock him out of the pre-med program and ruin his plans for the future. The day before the exam he wandered about campus in deep despair, consumed by guilt and anxiety. Finally, he says, he prayed:

“My mind reached toward God—a desperate yearning, begging, clinging to Him. ‘Either help me understand what kind of work I ought to do, or else perform some kind of miracle and help me to pass this exam.’” (72)

Once he placed the matter in God’s hands, Carson says he “felt at peace” (72). He commenced to study as hard as he could in the few hours remaining before the test—“I scribbled formulas on paper, forcing myself to memorize what had no meaning to me.” (73) When midnight came, Carson “flopped into my bed and whispered in the darkness, ‘God, I’m sorry. Please forgive me for failing You and for failing myself.’ Then I slept.” (73)

And then comes the dream that changed his life:

“While I slept I had a strange dream, and, when I awakened in the morning, it remained as vivid as if it had actually happened. In the dream I was sitting in the chemistry lecture hall, the only person there. The door opened, and a nebulous figure walked into the room, stopped at the board, and started working out chemistry problems. I took notes of everything he wrote.” (73)

When he woke up, Carson quickly wrote down all the problems he could remember, even though the final few faded away before he could record them. He looked up the problems in his textbook, figuring that his mind “was still trying to work out unresolved problems during my sleep.” (74)

But what happened next made him question the prosaic explanations of psychology. He went to the chemistry lecture hall, took his seat, and waited with 600 other students for the teacher to pass out the exam booklet.

“At last, heart pounding, I opened the booklet and read the first problem. In that instant, I could almost hear the discordant melody that played on TV with The Twilight Zone. In fact, I felt I had entered that never-never land. Hurriedly, I skimmed through the booklet, laughing silently, confirming what I suddenly knew. The exam problems were identical to those written by the shadowy dream figure in my sleep.” (74)

Without pausing to reflect on the strangeness of what was happening, he set to work on the exam, going as fast as he could so he would not forget the information he had received in his dream. “God, You pulled off a miracle,” he said as finished the test and left the lecture hall.

Once again he wandered the campus, this time in wonder and elation, urgently trying to make sense of things.

“I’d never had a dream like that before. Neither had anyone I’d ever known. And that experience contradicted everything I’d read about dreams in my psychological studies. The only explanation just blew me away. The one answer was humbling in its simplicity. For whatever reason, the God of the universe, the God who holds galaxies in His hands, had seen a reason to reach down to a campus room on Planet Earth and send a dream to a discouraged ghetto kid who wanted to become a doctor. I gasped at the sure knowledge of what had happened.” (75)

Carson passed the exam with a score of 97. The only problems he got wrong were the ones at the end, when his memory of the dream had begun to fade. From that point on his path toward a stellar medical career never faltered, and by the age of 33 he had become director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

But the significance of Carson’s miraculous dream extended far beyond helping him become a doctor. After this experience he was confident that God “had special things for me to do… I had an inner certainty that I was on the right path in my life—the path God had chosen for me. Great things were going to happen in my life, and I had to do my part by preparing myself and being ready.” (76)

What should we make of this story? First of all, we have to ask if he made the whole thing up. Aspiring politicians embellish their biographies all the time. It’s a rather neat little vignette, perfectly suited for a mass-market book. Carson had plenty to gain, and nothing to lose, by fabricating this feel-good tale of a dream of salvation.

Of course there is no direct way to validate the details of his experience. However, there are many indirect reasons, based on current scientific dream research, to indicate that what Carson described was not impossible but actually has some degree of plausibility. Setting aside his theological interpretation for a moment, we can look at the basic contours of Carson’s dream and identify several features that reflect well-known aspects of cognitive functioning during sleep.

To start, dream recall increases for many people during times of personal crisis. As clinical psychologists have long known, intensified dreams tend to emerge when a person is struggling with turbulent emotions and a fragile sense of identity. Increased dreaming is especially likely for people who perform pre-sleep prayers like Carson did the night before his dream. “Dream incubation” is the general term for rituals aimed at stimulating a revelatory dream, and religions all over the world have developed special techniques for this purpose. Modern researchers have found that if people go to sleep with an urgent question or concern in mind, they are highly likely to dream about it that night.

Indeed, those are the conditions that can generate a “big dream,” meaning a dream with unusual vividness, realism, and memorability. Carson’s experience would certainly qualify as a big dream in that sense.

Dreaming about a test or exam is among the most common types of recurrent dream. It has a history reaching back to ancient China and the dreams people many centuries ago had about passing, or failing to pass, the all-important civil service exams. People today often have exam nightmares long after they have been out of school, more evidence of the deep emotional power of these kinds of dreams.

There should be nothing surprising, then, about a college student who is very anxious about a test having a dream that relates directly to his waking concerns.

Although he later dismissed it, Carson’s initial psychological analysis of the dream has some merit. It seems likely that, after all that intense studying, he went to sleep and his unconscious mind made various connections that his conscious waking mind had not yet processed. The exam questions seemed familiar because it turned out that he actually understood the material much better than he thought he did. It would have been a much more miraculous story if he had received this dream and done well on the test without doing any studying beforehand.

In light of all this, we can recognize a plausible naturalistic core to Carson’s experience. We still cannot say with certainty that he really had this exact dream, but everything he described has a realistic basis in current scientific knowledge about sleep and dreaming.

Carson felt, however, that a naturalistic explanation of his dream was not enough. He adopted a theological interpretation that cast himself as a quasi-biblical figure of divinely sanctioned destiny. Strangely, he never said anything more about the “nebulous figure” who revealed the chemistry problems, and in most Christian contexts this would be a huge red flag. Any number of demonic temptations can enter people’s minds through dreams, and a “shadowy” character like the one in Carson’s dream would automatically be a target of suspicion. But Carson never has a moment’s doubt about the reliability of his mysterious dream teacher, trusting in the ultimate goodness of his desire to become a doctor. If the dream helped him reach that goal, it must be a dream from God.

Carson’s miraculous exam dream stands in dramatic contrast to the two dreams described by Barack Obama in his first book, Dreams From My Father. Obama’s dreams revolved around struggles with his complicated family history and efforts to reconcile himself with the haunting influence of his father. Both dreams occurred during a time of major life transition (after the death of his father, and on a journey to Africa to visit his father’s village), and both dreams are suffused with dark emotions of fear, anger, and sadness. Obama’s dreams led him to a more humble self-awareness of the enduring power of his family lineage, for good and for ill. In 2008, before Obama was elected, I wrote that a close look at these dreams “suggests that Obama is perhaps more temperamentally conservative and respectful of paternal authority than most Americans assume.”

Whereas Obama’s dreams had the effect of anchoring him more deeply in the communal traditions of his ancestors, Carson’s dream, or at least his interpretation of it, had the effect of elevating himself to a position of singular cosmic importance. It would not be too strong to say that Carson feels he is on a mission from God, a mission first revealed to him in a heaven-sent dream.

####

Note: This essay was first published in the Huffington Post on November 2, 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/kelly-bulkeley-phd/ben-carsons-illuminating-_b_8443254.html

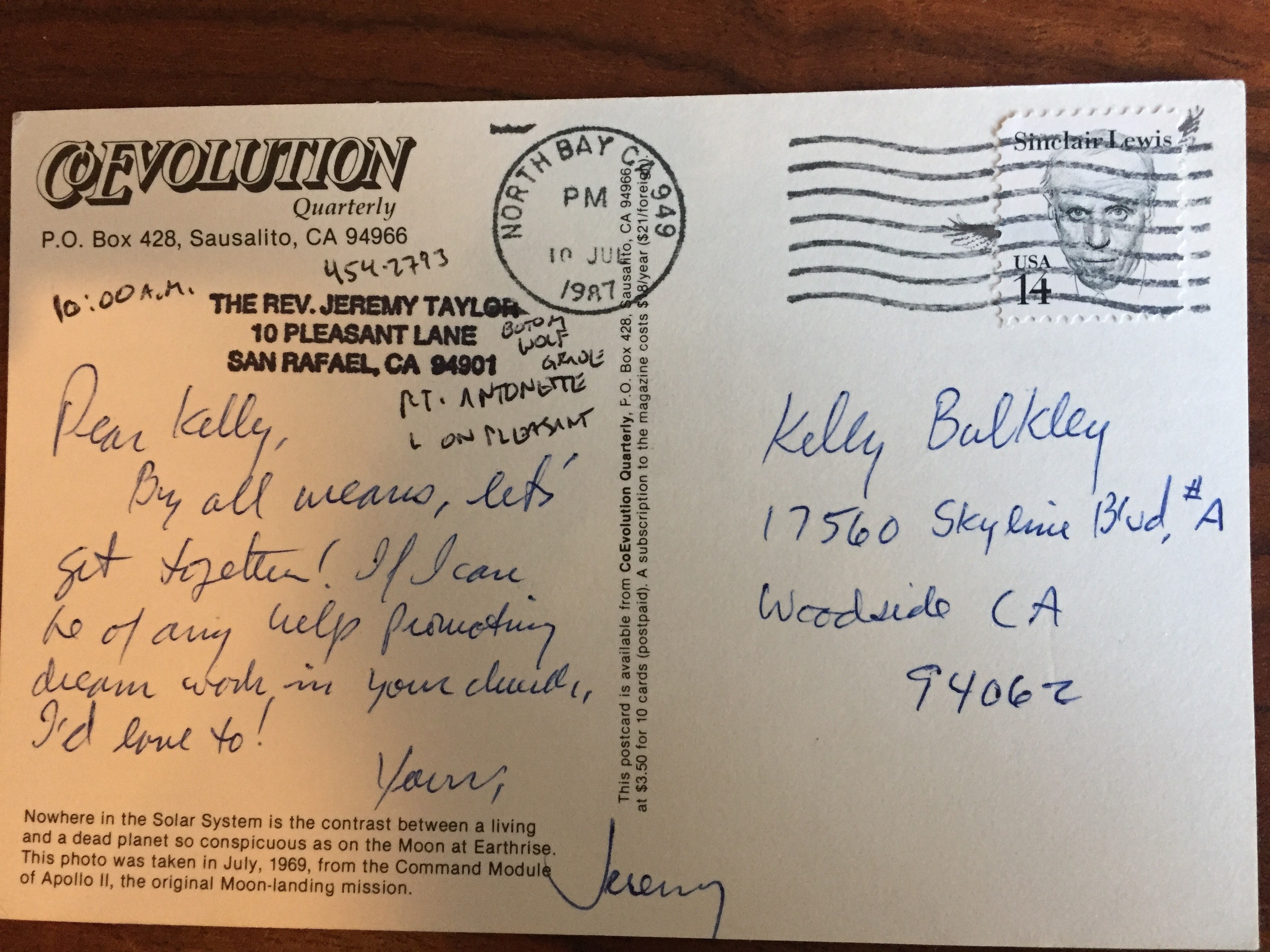

Following the death a few weeks ago of Jeremy Taylor and his wife Kathy, I spoke with their daughter Tristy, and we agreed that I would take responsibility for moving, storing, and preserving his professional books and papers. Tristy understands that her father had a major influence on the contemporary study of dreams, and his works will have an enduring historical significance for the field. I told her that my wife and I have recently begun working with an architect to design a study and library devoted to dream research on property we own near Portland, so I can offer a place where his collection will be available to other dream investigators in the future.

Following the death a few weeks ago of Jeremy Taylor and his wife Kathy, I spoke with their daughter Tristy, and we agreed that I would take responsibility for moving, storing, and preserving his professional books and papers. Tristy understands that her father had a major influence on the contemporary study of dreams, and his works will have an enduring historical significance for the field. I told her that my wife and I have recently begun working with an architect to design a study and library devoted to dream research on property we own near Portland, so I can offer a place where his collection will be available to other dream investigators in the future.

The Rev. Jeremy Taylor was one of the most prolific dream speakers and teachers of modern times. He traveled to every corner of the U.S., and to many countries around the world, reaching out to people and promoting greater awareness of dreaming. He combined his background as a Unitarian-Universalist minister with a deep familiarity with Jungian archetypal psychology to not only help people better understand their dreams, but to get them excited and energized about the amazing adventure of psychological growth and spiritual discovery that opens up once they start paying more attention to general human experience of dreaming.

The Rev. Jeremy Taylor was one of the most prolific dream speakers and teachers of modern times. He traveled to every corner of the U.S., and to many countries around the world, reaching out to people and promoting greater awareness of dreaming. He combined his background as a Unitarian-Universalist minister with a deep familiarity with Jungian archetypal psychology to not only help people better understand their dreams, but to get them excited and energized about the amazing adventure of psychological growth and spiritual discovery that opens up once they start paying more attention to general human experience of dreaming.

The close connection between dreaming and healing has a long and venerable history in Western civilization. The ancient Greek healing god Asclepius was worshipped throughout the Mediterranean for many centuries, with people praying to the god for dreams to help cure their physical and psychological suffering. The dream practices at the Asclepian temples became the deep spiritual basis for the Western medical tradition that many of us rely on today, although this fact is rarely acknowledged or appreciated.

The close connection between dreaming and healing has a long and venerable history in Western civilization. The ancient Greek healing god Asclepius was worshipped throughout the Mediterranean for many centuries, with people praying to the god for dreams to help cure their physical and psychological suffering. The dream practices at the Asclepian temples became the deep spiritual basis for the Western medical tradition that many of us rely on today, although this fact is rarely acknowledged or appreciated. Ben Carson, the retired neurosurgeon and leading Republican contender for the Presidency, says that his life was changed by a shadowy figure who appeared in a dream and gave him special advice at a time of crisis. Not since Barack Obama’s 2004 memoir Dreams From My Father has a presidential candidate shared such valuable insight into his personal dreaming experience.

Ben Carson, the retired neurosurgeon and leading Republican contender for the Presidency, says that his life was changed by a shadowy figure who appeared in a dream and gave him special advice at a time of crisis. Not since Barack Obama’s 2004 memoir Dreams From My Father has a presidential candidate shared such valuable insight into his personal dreaming experience.