This is the written version of the presentation (with a 7-minute time limit) I made on Sunday, January 11, to the attendees of the Dream x Engineering Symposium at the MIT Media Lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Thanks to Adam Horowitz, Michelle Carr, Karen Konkoly, and all the others who organized and participated in the symposium.

Dreaming and Technologies of the Sacred

Thank you, it’s an honor to be here.

I’d like to share with you a working hypothesis, drawn from the historian of religions Mircea Eliade, that I believe has practical importance for dream engineering:

Any dream technology will be more effective the more sacred, and the less profane, the experiential context in which it is deployed.

Here is a quote from his 1959 book:

The first possible definition of the sacred is that it is the opposite of the profane… The sacred tree, the sacred stone are not adored as stone or tree; they are worshipped precisely because they are heirophanies, because they show something that is no longer stone or tree but the sacred, the ganz andere… The sacred is saturated with being.

Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and The Profane (1959), 12

I can gloss this passage by saying:

The sacred is conceived as a break into ordinary time and space, a rupture in the monotony and homogeneity of profane existence.

The sacred brings us closer to the really real, the time of origins, the center of the cosmos.

Without having more time to elaborate on this concept in the abstract, let me offer two sources of empirical evidence in favor of my working hypothesis.

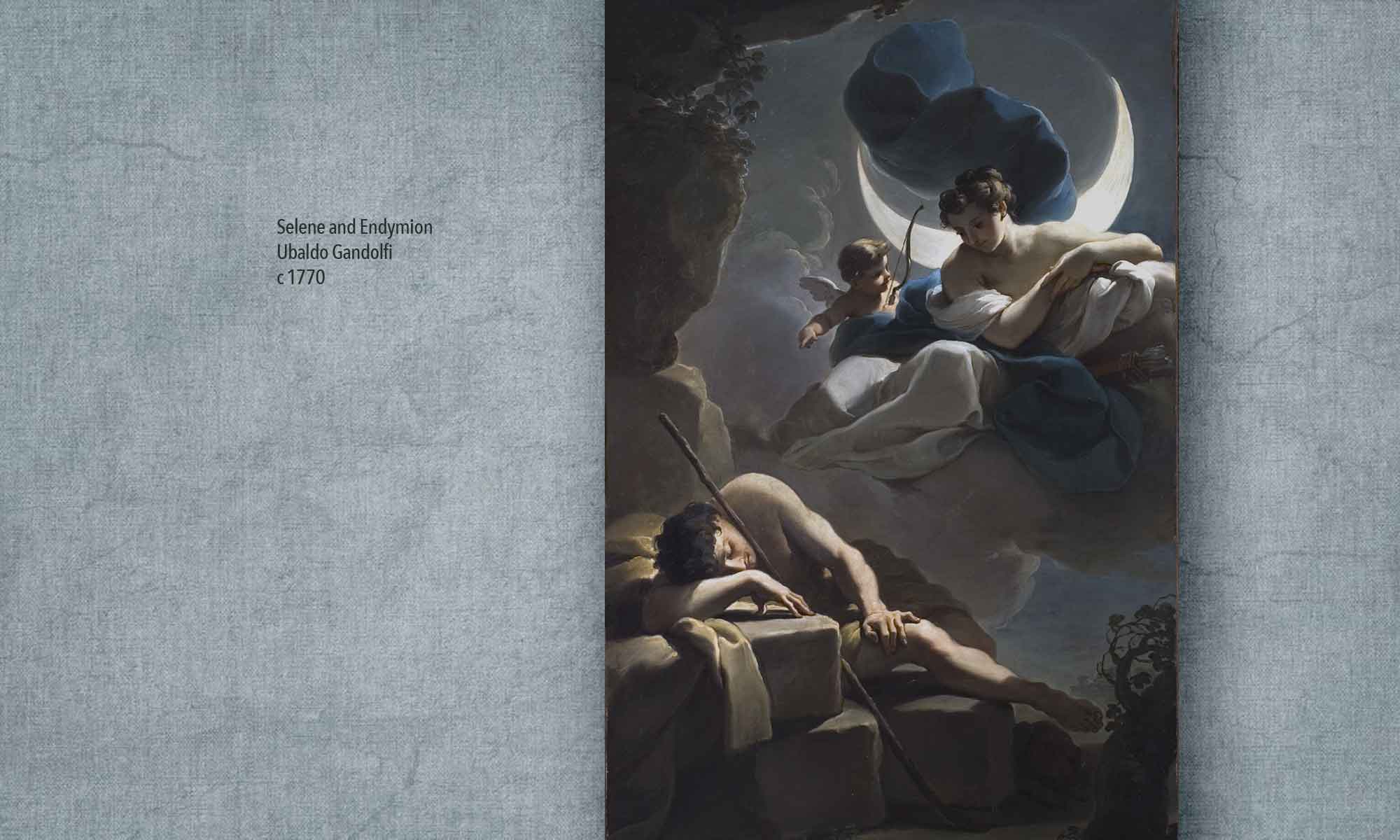

First are the religious rituals of dream incubation practiced throughout history, in cultures all over the world, all of which share the goal of moving the dreamer away from the profane, and towards the sacred: by means of fasting, prayer, and purifications, and by means of sleeping in a special place, like a mountain, cave, or graveyard.

Dream incubation is the original form of dream engineering, and its guiding principle is maximizing the sacred qualities of the dreamer’s experience.

To be clear: It doesn’t matter if you believe it is an experientially sacred context, it matters if the dreamer believes it’s an experientially sacred context.

The second source of evidence is the “lab effect” that has bedeviled scientific sleep research from its earliest days.

I’ll share three comments that sleep lab researchers have made to me over the years:

- Robert Van de Castle: after thousands of nights of sleep lab observations, he only heard of one reported wet dream.

- Allan Hobson: he admitted the most interesting and intense types of dreams usually happen outside the lab.

- Ernest Hartmann: he found that when chronic nightmare sufferers slept in his lab they had fewer nightmares, because they knew they were being observed all night and felt safer because of it.

From the perspective of Eliade and the working hypothesis I’m offering to you, the lab effect is a measure of how a profane setting can homogenize dreaming by diminishing its range and intensity.

In closing, I will mention two new efforts to develop dream technologies that put the working hypothesis into practice.

First is the Elsewhere.to app for dream journaling, for which I serve as a research consultant and investor.

There is, of course, a profane quality to the cell phone for many people. But starting with its name, Elsewhere invites users to go beyond the profane space of the “this-here,” and to open themselves to another, more sacred way of perceiving and experiencing the world and their lives, through the prism of their dreams and the deep archetypal patterns that emerge when you track them over time.

The design, graphics, layout, features, image styles, and interpretation modes of Elsewhere have all been crafted by people who share this deep respect for the innate wisdom of the dreaming mind.

The second new effort represents a much older form of technology, a library, which I’m calling the Dream Library, nearly completed, intended as a long-term archive of books, journals, and art works related to dreaming.

Set in a rainforest, in a building of hand-crafted wood, the Dream Library will offer a permanent physical space for projects and gatherings devoted to the study of dreaming.

It is designed to be as non-profane as possible, and to elicit a tangible sense of the sacred potentials in everyone’s dreams.

And perhaps, one day, it will be the site of a future gathering of dream engineers.

Thank you.

####

As both a dreamer and a researcher, I find myself completely enchanted by the

As both a dreamer and a researcher, I find myself completely enchanted by the  It may seem hard to believe for those who rarely remember their dreams, but psychologists have found strong evidence that sleep and dreaming are closely intertwined with the dynamics of memory. Whether or not the dreams are consciously recalled in waking, the dreaming process seems to play a valuable role in the underlying system by which our memories are created, stored, and retrieved.

It may seem hard to believe for those who rarely remember their dreams, but psychologists have found strong evidence that sleep and dreaming are closely intertwined with the dynamics of memory. Whether or not the dreams are consciously recalled in waking, the dreaming process seems to play a valuable role in the underlying system by which our memories are created, stored, and retrieved. Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.

Early in my career, I had attitude about writing “secondary” texts. I didn’t want to write about what other people thought, I wanted to write about my own ideas. That’s why when the opportunity arose to write a book intended as an introductory textbook for college students, I hesitated. The offer came by way of Sybe Terwee, a psychoanalytic philosopher from the Netherlands who had recently co-hosted the 1994 annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams at the University of Leiden. Sybe had been contacted by Greenwood/Praeger, an American publisher with a large psychology catalog, asking him if he would be interested in writing an introductory text on dream psychology. He was unable to do so, but he suggested me as an alternative, and put them in touch with me. This was a big thrill for a young scholar, and I wanted to show Sybe I was worthy of his trust.

Houses and homes are among the most frequent elements appearing in dreams, with a wide range of literal and symbolic meanings.

Houses and homes are among the most frequent elements appearing in dreams, with a wide range of literal and symbolic meanings. The bizarre contents of dreaming can easily seem like the products of mental deficiency. “Children of an idle brain” is what Mercutio calls them in Romeo & Juliet (I.iv.102). Many scientists today essentially agree with Mercutio that the weird absurdities of dreams are evidence of diminished cognitive functioning during sleep.

The bizarre contents of dreaming can easily seem like the products of mental deficiency. “Children of an idle brain” is what Mercutio calls them in Romeo & Juliet (I.iv.102). Many scientists today essentially agree with Mercutio that the weird absurdities of dreams are evidence of diminished cognitive functioning during sleep.