It seems that every pundit on the planet has taken a shot at explaining the phenomenal rise and mercurial character of Donald Trump, currently the leading contender to become the Republican nominee for US President. A recent op-ed piece by Timothy Egan in the New York Times, “A Unified Theory of Trump,” suggested a novel and I believe entirely plausible explanation for Trump’s behavior as a candidate: he is chronically sleep deprived.

It seems that every pundit on the planet has taken a shot at explaining the phenomenal rise and mercurial character of Donald Trump, currently the leading contender to become the Republican nominee for US President. A recent op-ed piece by Timothy Egan in the New York Times, “A Unified Theory of Trump,” suggested a novel and I believe entirely plausible explanation for Trump’s behavior as a candidate: he is chronically sleep deprived.

Egan pointed to Trump’s comments last November in which he boasted about his disinterest in sleep. As reported by Nara Schoenberg in the Chicago Tribune, Trump told a crowd in Springfield, Illinois that “I’m not a big sleeper, I like three hours, four hours, I toss, I turn, I beep-de-beep, I want to find out what’s going on.” A few days later Trump told Henry Blodget in an interview for Business Insider that he can get by on as little as one hour of sleep. Here is an excerpt from the interview; the sleep discussion comes at the very beginning:

HENRY BLODGET, CEO AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF BUSINESS INSIDER: You have an incredible work ethic, which is clearly part of your success. You’re tweeting at 3 o’clock in the morning, you’re up all night.

DONALD TRUMP: It’s part of my campaign. [Conservative radio host] Mark Levin said to me last night, I had a dinner-show at 8:30. He says, “I saw you on ‘Morning Joe’ at 7, I saw you in the debate. Where do you get the energy?” he said. I said, “Mark, you know what, I got one hour of sleep last night. Because I flew from Milwaukee at 2:30 in the morning. You know, by the time you’re finished up with all the stuff and the interviews.” It was a successful debate, so I stayed around.

I then flew, I went to New Hampshire. I went to a hotel, I stayed for one hour, because I got there at 5. And by the time I got there, I had to get up to get out at 6:30 something. So I slept for one hour over there.

He said, “Where do you get the energy?”

HB: So where do you get it? Where does it come from?

DT: Genetically. My father was very energetic, my mother was very energetic. He lived to a very old age and so did my mother. I believe that I just have it from my father, from my parents. They had wonderful energy.

In her Huffington Post commentary, “Can Sleep Deprivation Explain Donald Trump’s Behavior?” Krithika Varagur noted that in his 2004 book Trump: Think Like a Billionaire, he “claimed to sleep only from 1:00 a.m. to 5:00 a.m., in order to gain a competitive advantage in his dealings. He advised readers, ‘Don’t sleep any more than you have to. … No matter how brilliant you are, there’s not enough time in the day.’”

I won’t speculate about Trump’s genetics, but I agree with Schoenberg, Egan, and Varagur that his behavioral patterns are characteristic of someone with chronic sleep deprivation, the symptoms of which include emotional imbalance, sudden mood swings, cognitive deficits, poor judgment, memory loss, irritability in social situations, increased appetites, loss of creativity, the tendency to continue with an error despite contrary evidence, and an inability to recognize and adjust to new conditions. Most of these symptoms do seem applicable to Trump. As Egan put it,

“His judgment is off, and almost always ill informed. He has trouble processing basic information. He imagines things. He shows a lack of concentration… in addition, Trump is given to inchoate bursts of anger and profanity. He creates feuds. In his speeches, he picks up on the angry voice in the mob and then amplifies it.”

But if this theory about Trump is true, then his political success seems even more bizarre than ever. How can someone who flaunts his psychological dysfunction be winning the fervent support of a large portion of the American electorate?

The answer may be embedded in the question. Trump’s supporters themselves may have a tendency to chronic sleep deprivation.

The behavioral signs are consistent with this idea. People who support Trump are remarkably unyielding in their attachment to him; nothing anyone says will change their minds. As Trump himself commented in January, “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.” His supporters seem to include many people who are angry, suspicious of reason, socially irritable, and uncreative in the sense of seeking a return to an earlier, simpler time, when America used to be great.

Stronger evidence comes from demographic studies of sleep. Trump’s supporters tend to be people at the lower end of the income scale, less educated, and, in their own words, feeling besieged by outside forces threatening to overwhelm the country. Empirical research has shown that people in precisely those demographic conditions are more prone to suffer insomnia and problems sleeping. For example, Sara Arber at the University of Surrey has shown correlations in the British population between poor sleep and low socio-economic status. Here is how I describe her findings in chapter 4 of my book Big Dreams:

“Research by Sara Arber and her colleagues at the Center for the Sociology of Sleep at the University of Surrey has found clear connections between socioeconomic status and sleep quality. In a study based on interviews with 8,578 British men and women between the ages of 16 and 74, Arber and her colleagues identified several social and economic factors associated with increased sleep problems: unemployment, low household income, low educational achievement, and living in rented or public housing. Women had worse sleep problems than men, and divorced or widowed people had worse sleep problems than married people. Overall, their study found that disadvantages in social and economic life were strongly correlated with poor quality sleep. Noting the negative health consequences of sleep deprivation, Arber and her colleagues suggested that “disrupted sleep may potentially be one of the mechanisms through which low socioeconomic status leads to increased morbidity and mortality.”

The last point bears emphasis. Poor socioeconomic conditions can lead to poor sleep, which in turn can lead to increased health problems and a shorter lifespan. Sleep seems to be a pressure point where adverse social forces can directly and negatively impact a person’s physiological health.

My research with the Sleep and Dream Database has also found that people at the low end of the economic scale tend to have more insomnia and trouble sleeping. In a 2007 survey I found, consistent with Arber et al.’s research, that people with higher education and higher annual income tended to have less insomnia than people with lower education and lower annual income. A 2010 survey found the same pattern: people without college degrees had somewhat worse insomnia than people with a college degree. On the personal finances question, people with the lowest annual income reported having worse insomnia than did the people with the highest annual incomes. (I discuss these surveys at greater length in chapter 4 of Big Dreams.)

Most Americans are sleep deprived not by choice or genetics, but because of the relentless stress and pressure of modern life. For those Americans at the lower end of the economic scale, with fewer opportunities and more anxieties about the worsening condition of the country, it becomes difficult to preserve normal, healthy patterns of sleep.

And then Donald Trump comes along and says sleep deprivation is nonsense, that’s just what losers think when they see a high-energy individual with a strong work ethic. Trump shows people how to re-brand their loss of sleep as a badge of honor, reconceive their misfortune as a virtuous strength, and transform their diminished inner life into an outward projection of aggressive confidence. It seems to work for him, and the implicit promise of his campaign is that it will work for his supporters, too.

References:

Arber, Sara, Marcos Bote, and Robert Meadows. “Gender and socio-economic patterning of self-reported sleep problems in Britain,” Social Science & Medicine 68 (2009): 281-289.

Arber, Sara, Robert Meadows, and S. Venn. “Sleep and Society,” in The Oxford Handbook of Sleep and Sleep Disorders (Charles Morin and Colin Espie, ed.s). New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, 223-247.

Note: this essay first appeared in the Huffington Post on March 9, 2016.

Childhood is a time of frequent and intense dreaming for many people. Often these nocturnal experiences from early life have a dark hue—children are especially prone to nightmares, sleep paralysis, and night terrors. But children are also more likely than adults to experience magical dreams of flying and lucid dreams of self-awareness. The whole wild world of dreaming, in all its strange complexity, seems more accessible in childhood than it is later in life.

Childhood is a time of frequent and intense dreaming for many people. Often these nocturnal experiences from early life have a dark hue—children are especially prone to nightmares, sleep paralysis, and night terrors. But children are also more likely than adults to experience magical dreams of flying and lucid dreams of self-awareness. The whole wild world of dreaming, in all its strange complexity, seems more accessible in childhood than it is later in life. The first comes from “SpongeBob SquarePants,” which first aired in 1999 on the Nickelodeon network and has gone on to become one of the most popular cartoons of all time. An episode in season 5, titled “

The first comes from “SpongeBob SquarePants,” which first aired in 1999 on the Nickelodeon network and has gone on to become one of the most popular cartoons of all time. An episode in season 5, titled “ Hawkgirl’s dream is perhaps the most intense and frightening of all. After a false awakening that gives her a moment of deceptive reassurance, Dr. Destiny binds her wings and sends her plunging down to earth, straight into a yawning grave in which she is buried alive under a mound of dirt. For a superhero whose special power is flight, this would be a terrifying nightmare indeed.

Hawkgirl’s dream is perhaps the most intense and frightening of all. After a false awakening that gives her a moment of deceptive reassurance, Dr. Destiny binds her wings and sends her plunging down to earth, straight into a yawning grave in which she is buried alive under a mound of dirt. For a superhero whose special power is flight, this would be a terrifying nightmare indeed. On Friday, February 19, I will visit with

On Friday, February 19, I will visit with  The past one hundred years of human history have been dramatically transformed by the invention of several new technologies, each of which has impacted people’s lives in profound and complicated ways.

The past one hundred years of human history have been dramatically transformed by the invention of several new technologies, each of which has impacted people’s lives in profound and complicated ways.

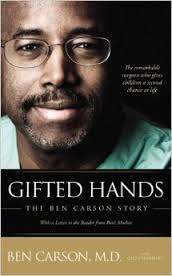

Ben Carson, the retired neurosurgeon and leading Republican contender for the Presidency, says that his life was changed by a shadowy figure who appeared in a dream and gave him special advice at a time of crisis. Not since Barack Obama’s 2004 memoir Dreams From My Father has a presidential candidate shared such valuable insight into his personal dreaming experience.

Ben Carson, the retired neurosurgeon and leading Republican contender for the Presidency, says that his life was changed by a shadowy figure who appeared in a dream and gave him special advice at a time of crisis. Not since Barack Obama’s 2004 memoir Dreams From My Father has a presidential candidate shared such valuable insight into his personal dreaming experience.