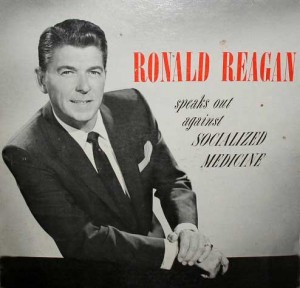

A conversation about the American Dream with Martin Anderson, biographer of Ronald Reagan

Thanks to the kind intercession of Tom Campbell, then Dean of the Haas School of Business at U.C. Berkeley, I had the opportunity to interview Martin Anderson by telephone on November 5, 2007. Anderson was an administration official during the presidency of Ronald Reagan and has written and edited several books about Reagan, including Reagan, In His Own Hand: The Writings of Ronald Reagan That Reveal His Revolutionary Vision for America (2001). Reagan’s presidency is often associated with a particularly sunny, Westernized vision of the American Dream, and I hoped Anderson could provide a well-informed description of his politically conservative ideals.

Our conversation got off to a difficult start. I must not have been very clear in my initial description of what I wanted to discuss (it’s a hard project to describe in a few words), and Anderson reacted as if I were taking a critical approach to Reagan’s reputation as a napper. It’s true, I was curious about that and planned to ask about it eventually, but Anderson immediately declared that Reagan “never napped,” and he dismissed any suggestion that Reagan was ever less than fully fit and alert both mentally and physically while President. Anderson said he challenged anyone to find a photograph that showed Reagan napping (I made a quick check of Google images and found nothing). I expressed surprise at this, since the legend that Reagan enjoyed a daily siesta is widespread and even a point of pride among conservatives, who regard his regular afternoon naps as endearing expressions of equanimity and good sense. The most Anderson would allow is that there may have been “brief closings of his eyes” during meetings, but nothing that would count as a full nap.

Of much greater interest to Anderson, and to me as well, was the nature of Reagan’s political idealism. According to Anderson, Reagan’s boldest political initiatives were inspired by “dreams” and “visions” that gave him a profound sense of meaning, purpose, and direction throughout his political career. It’s not clear to what extent these inspirations were related to actual dreams during sleep, but in Anderson’s view they reflected an admirable openness to sudden intuitions and calls to action. The greatest of these dreams was that of a nuclear-free world. Reagan was a pacifist in his 20’s, and Anderson said he never lost his idealistic vision of a world beyond the horrors of war. At the 1976 Republican National Convention, where he narrowly lost the nomination to Gerald Ford, Reagan gave a final speech in which he surprised everyone by calling for an elimination of nuclear weapons, a very un-Republican proposal. “It was always Ronnie’s dream that the world would be free of nuclear weapons.” Anderson also pointed to the “Star Wars” anti-missile defense system as an instance where Reagan made a sudden decision, unanticipated by even his closest aides, to pursue a highly idealistic effort to end the threat of nuclear war.

As someone who cast his first two presidential votes against Reagan, I found it hard to reconcile Anderson’s glowing portrait with the Reagan I perceived from 1980 to 1988. At the time, his visionary idealism made less of an impression on me than his administration’s unwillingness to deal with growing problems with the environment, civil rights, poverty, etc. Yet Anderson persuaded me to recognize in Reagan an authentic visionary quality, a reliance on deep personal intuitions of purpose and truth. I may disagree fundamentally with the purposes to which Reagan directed his intuitions, but I can still respect him as a dreamer whose political success derived in large part from his ability to communicate his dreams to others. His mojo just didn’t work on me.

Soul, Psyche, Brain: New Directions in the Study of Religion and Brain-Mind Science

Soul, Psyche, Brain: New Directions in the Study of Religion and Brain-Mind Science Spiritual Dreaming: A Cross-Cultural and Historical Journey.

Spiritual Dreaming: A Cross-Cultural and Historical Journey.  Dreamcatching : Every Parent’s Guide to Exploring and Understanding Children’s Dreams and Nightmares.

Dreamcatching : Every Parent’s Guide to Exploring and Understanding Children’s Dreams and Nightmares.