“Dreamy” is one of the adjectives most often used to describe the cinematic art of David Lynch, and justifiably so. Below are two journal articles I have written about his works in which I explore and celebrate his aesthetic dreaminess, especially in the films Mulholland Drive, Lost Highway, Blue Velvet, and the television series Twin Peaks and Twin Peaks: The Return.

“Dreamy” is one of the adjectives most often used to describe the cinematic art of David Lynch, and justifiably so. Below are two journal articles I have written about his works in which I explore and celebrate his aesthetic dreaminess, especially in the films Mulholland Drive, Lost Highway, Blue Velvet, and the television series Twin Peaks and Twin Peaks: The Return.

The Essential Dreaminess of “Twin Peaks: The Return”

(International Journal of Dream Research, vol. 15, no. 1 (2022), 174-179)

Dreams and Twin Peaks the Return Bulkeley

Dreaming and the Cinema of David Lynch

(Dreaming, vol. 13, no. 1 (2003), 49-60)

Abstract: This essay explores the influence of dreams and dreaming on the filmmaking of David Lynch. Focusing particular attention on Mulholland Drive (2001), Lost Highway (1997), Blue Velvet (1986), and the television series Twin Peaks (1990-91), the essay will discuss the multiple dream elements in Lynch’s work and how they have contributed to the broad cultural influence of his films. Lynch’s filmmaking offers an excellent case study of the powerful connection between dreaming and movies in contemporary American society.

More than perhaps any other contemporary director, Lynch draws upon dream experience as a primal wellspring of his creative energy. Dreams and dreaming suffuse every moment of his approach to filmmaking. The disturbing impact of watching Mulholland Drive and his other works (especially Blue Velvet, Lost Highway, and the television series Twin Peaks) derives in large part from his uncanny skill in using cinema as a means of conveying the moods, mysteries, and carnivalesque wildness of our dreams. One of his biographers, Chris Rodley, puts it this way:

“The feelings that excite him most are those that approximate the sensations and emotional traces of dreams: the crucial element of the nightmare that is impossible to communicate simply by describing events. Conventional film narrative, with its demand for logic and legibility, is therefore of little interest to Lynch…. Insecurity, estrangement, and lack of orientation and balance are sometimes so acute in Lynchland that the question becomes one of whether it is ever possible to feel ‘at home’…. If Lynch could be called a Surrealist, it is because of his interest in the ‘defamiliarization’ process and the waking/dream state—not in his frequent use of the absurd or the incongruous.” (Rodley, 1997)

On a first viewing Lynch’s works seem baldly psychoanalytic in their emotional preoccupations, almost to the point where there does not seem to be anything for a latter-day Freudian or Jungian to interpret. All the great passions of the unconscious are right there, out in the open, without any disguise, repression, or arcane symbolism. Although I do believe psychoanalytic film criticism has its uses, that is not the path I want to follow in this essay. My interest here is both more focused and more expansive. First, I want to identify and describe several specific means by which dreaming is woven into Lynch’s approach to filmmaking. These include the use of dreaming as a narrative structuring device, the inclusion of scenes in which characters experience a dream, the inclusion of dialogue in which characters discuss dreams, and the use of Lynch’s own dream experience as an inspirational source for his creative work. After that, I want to reflect on the role these multiple dream elements have played in the broader cultural influence of his films. Lynch’s filmmaking offers an excellent case study of the powerful connection between dreams and movies in contemporary American society, and at the end of the essay I will suggest the common nickname for Hollywood—the “dream factory”—is not merely a figure of speech but is in fact an accurate description of the profoundly interactive influence of films on dreaming and dreaming on films. It is this mutual interplay of dreams and movies that ultimately interests me, and my hope is that this essay will open a new path toward a better understanding of that dynamic relationship.

Dreams and dreaming play several different roles in Lynch’s filmmaking. The following summary of the most prominent of these roles is not intended to be comprehensive or exhaustive. Indeed, a complete accounting of these roles would require a detailed review of Lynch’s whole body of work. But even the limited description I am offering should be sufficient to prove my basic point, which is that dreams and dreaming play an absolutely central role in his filmmaking process. Is there any director who does more than Lynch to integrate dreaming and filmmaking? Perhaps so; I would enjoy hearing someone try to make the case. For the present, I offer the following analysis not to prove Lynch’s superiority to other directors, but rather to illustrate the dream-inspired artistry of one particular director who has made, and is continuing to make, a substantial contribution to contemporary attitudes toward the dream-film connection.

Dreaming as Narrative Structure. For many viewers the most striking feature of Mulholland Drive (2001) is the abrupt rupture in the narrative about two-thirds of the way through the film. Although there are several other story threads woven in and out of Mulholland Drive, the main narrative follows the experiences of Betty (Naomi Watts), a pert young blond who has just arrived in Hollywood with hopes of becoming an actress but who instead finds herself caught up in a dangerous mystery involving a dark-haired woman with amnesia (Laura Harring) who adopts the name “Rita” from a movie poster (among other things, Mulholland Drive is a wicked satire of the ultimate emptiness of “Hollywood dreams”). Betty and Rita find a little blue box that matches the strange blue key they found in Rita’s purse, but just when they go to put the key in the box, Betty all of a sudden wakes up—and even though it’s still her, it soon becomes clear that it’s not her, at least not the same person whose life viewers have been following for the past hour and a half. This Betty (now her name is Diane Selwyn) is darker, angrier, and full of bitterness and despair. Likewise, many of the same people from the earlier scenes are still present, but they are different, too, with different names, personalities, and relationships to one another. Confronted with all these sudden changes, viewers are forced into a radical reconsideration of their understanding of all the preceding scenes in the movie. Each new scene that follows this profound shift in the narrative takes on an added layer of meaning in its retrospective revelation of what was happening in the earlier scenes, and this in turn creates a mounting sense of inexplicable foreboding as the story builds to a climax. (A similar narrative rupture occurs in Ron Howard’s film A Beautiful Mind, which won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Best Director the same year as Lynch was nominated for Best Director for Mulholland Drive. The different use of this narrative device in the two films is a good measure of the difference between mainstream Hollywood movies and Lynch’s distinctive, “Jimmy Stewart from Mars” brand of filmmaking.)

When the film finally ends, with Betty’s/Diane’s horrific suicide, viewers are still left with several open questions about the precise relationship of the various scenes to each other. It is plausible to think of the “second” Betty as the “real” one, who was having a dream that involved the fantasized experiences of the “first” Betty (the image of a red pillow frames both ends of the “first” Betty’s scenes). But even that interpretation does not account for everything (e.g., how exactly does the willful director Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux) fit into the dreaming/waking interaction?), and in the end it seems contrary to the spirit of the movie to insist on any one explanatory framework.

The film Lost Highway (1997) also involves an unexpected rupture in the narrative. Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) is a musician plagued by the fear that his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette) is being unfaithful to him. When she is found horribly murdered in their home, Fred is arrested, convicted, and sentenced to death, even though he professes his innocence. While Fred is sitting despondently in his prison cell, something strange happens—and suddenly it’s not him any more, but a young man named Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty) sitting in the cell. The baffled authorities have no choice but to let Pete go, and he returns home to his parents and girlfriend. Viewers are naturally at a loss to explain what has happened, and whatever initial expectations they may have formed about where the story was going have been abruptly dashed. Funny things start happening to Pete, and soon he meets a beautiful, vivacious woman whom viewers immediately recognize as the same woman as Fred’s wife, even though she says her name is Alice Wakefield. Pete and Alice fall in love, but their torrid affair soon leads to violence, betrayal, and death. When Pete’s life has finally collapsed into ruins, when Alice has abandoned him and he realizes that his life has been completely destroyed, he suddenly disappears—and Fred is back. Dazed, Fred gets in his car and speeds away down a dark highway. The police are right behind him with flashing lights and red sirens, and the film ends with Fred becoming consumed by a violent physical frenzy.

So what was happening during the interlude with Pete? Was Fred having a dream? Did Fred really murder his wife (something hinted at by one of his dreams—more on that later), and in his abject despair did he fantasize being an entirely different person? And in the end was the fantasy not strong enough to escape the gravitational pull of the agonies of his “real life?” I am reminded of the famous painting called “The Prisoner’s Dream” in which a downtrodden young man is sleeping in a jail cell, while an ethereal version of himself lifts off from his body and soars through the metal bars at the window, out into the freedom of the air and the light. The painting testifies to the power of dreaming to relieve people’s suffering by imagining different and better lives for themselves. Freud’s notion of dreams as disguised fulfillments of repressed wishes is based on this power, and even though Lynch is reluctant to endorse any psychoanalytic interpretation of his films he does grant that what happens to Fred in Lost Highway could be considered a “psychogenic fugue,” i.e. a form of amnesia involving a flight from reality. He says he had never heard of that mental condition before making the film, but appreciated learning about it later—“it sounds like such a beautiful thing—‘psychogenic fugue.’ It has music and it has a certain force and dreamlike quality. I think it’s beautiful, even if it didn’t mean anything.” (Rodley, 1997)

Does it mean anything, then, that Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive end ambiguously, tantalizing viewers with unanswered questions about the basic narrative structure of the films? If nothing else, this had the perhaps predictable consequence of stimulating widespread criticism from viewers who accused the films of being too hard to understand. In the eyes of many viewers, Lynch had failed a filmmaker’s primary responsibility to tell a coherent story. According to critics, either he didn’t know how to present a comprehensible narrative, or he didn’t want to because he was more interested in self-indulgent artistry than in communicating with an audience.

The modest box office returns for both movies underscores this failure to attract or satisfy a broad public audience. In appraising Lynch’s films it must be noted that they have always earned more critical than commercial success, indicating that the appeal of his work may be very intense for a limited group of people (he has a remarkable number of passionately devoted fans) but does not extend very far into the general population. Although I would grant the criticism that some of his films are more emotionally effective and aesthetically powerful than others (for example, I would argue that Blue Velvet is a better film than Wild at Heart), I believe it misses the point to condemn Lynch’s films for their failure to provide clear, conventional narrative frameworks for their viewers. Movies like Mulholland Drive and Lost Highway remind me of certain Hindu myths in which people become so entangled in each other’s dreams and dreams-within-dreams that readers cannot help but feel confused about the basic existential question of what is real. For example, the Yogavasistha, a philosophical treatise written sometime between the tenth and twelfth centuries C.E. in Kashmir, tells the story of a hunter meeting a sage in the woods. The sage telling the hunter a story about how the sage once entered the dream of someone else and lived in that person’s world until it was suddenly destroyed by a flood at doomsday; then the sage thinks he wakes up, but another sage comes and tells him they are both characters in someone else’s dream. This makes the first sage wake up again, and he now realizes he needs to get back to his real body. He isn’t sure how to do this, however, and the story ends with no clear-cut resolution to his dilemma. Commenting on this myth, historian of religions Wendy Doniger says

“As the tale progresses, we realize that our confusion is neither our own mistake nor the mistake of the author of the text; it is a device of the narrative, constructed to make us realize how impossible and, finally, how irrelevant it is to attempt to determine the precise level of consciousness at which we are existing. We cannot do it, and it does not matter.” (Doniger, 2001)

The Hindu myths, like Lynch’s films, draw upon the powerful realness of dreaming to frustrate people’s conventional narrative expectations and provoke new reflection and new self-awareness. Their dreamy visions are enticing invitations to explore experiential realms beyond the boundaries of ordinary rational consciousness and personal identity.

Dream Scenes. Many characters in Lynch’s films are shown having experiences that are explicitly identified as dreams. These scenes all include the basic elements of a character going to sleep, dreaming, then waking up and trying to figure out what the dream means. Here are three examples:

Fred in Lost Highway tells his wife Renee about a dream he had in which he comes into their house and hears her calling his name. He sees a fire blazing in the fireplace, and pink smoke coming from the hall. He walks into their bedroom and finds her—“There you were….lying in bed….but it wasn’t you….It looked like you….but it wasn’t.”(Hughes, 2001). Renee looks up at him and suddenly screams, as if being struck by something, and then Fred wakes up. Deeply shaken, he looks across the bed to the “real” Renee for reassurance. But instead of his wife he sees the leering face of “The Mystery Man” (Robert Blake), a demonic figure who haunts Fred throughout the film (In a case of life imitating art, Blake was recently arrested for the murder of his wife). Fred cries out in terror, turns on the light switch, and finds his wife right there, looking at him with concern. He lays back in bed, shaking.

Writing has always been a relational process for me. Relationships with an imagined audience, with the people who have taught and influenced me, sometimes with co-authors, and always with the energies of inspiration I personify as Muses—without them, I would never care enough to put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard. With them, I’ve found lifelong joy and a singular sense of purpose in crafting ideas into tapestries of written language that can be shared with others.

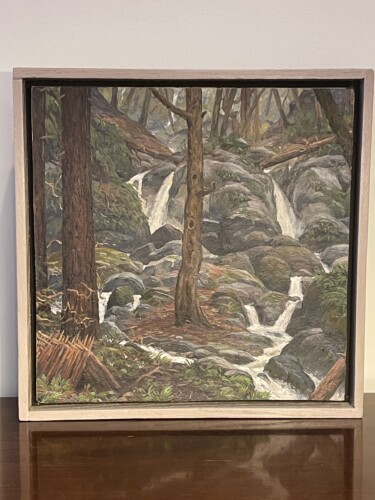

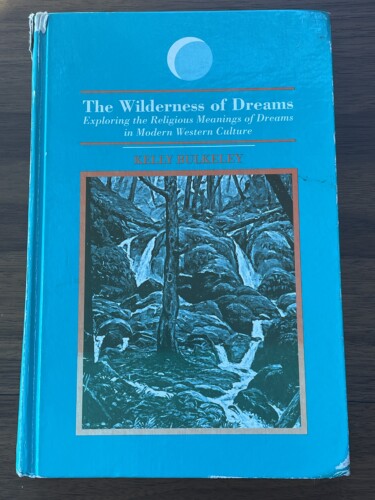

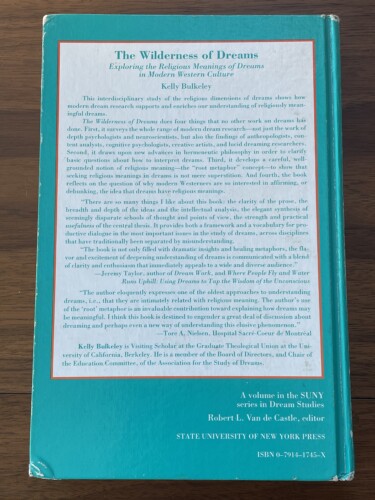

Writing has always been a relational process for me. Relationships with an imagined audience, with the people who have taught and influenced me, sometimes with co-authors, and always with the energies of inspiration I personify as Muses—without them, I would never care enough to put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard. With them, I’ve found lifelong joy and a singular sense of purpose in crafting ideas into tapestries of written language that can be shared with others. It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend Josh Adam, who has become one of the great landscape painters of our generation. Generous back-cover endorsements were provided by Jeremy Taylor and Tore Nielsen, a Unitarian-Universalist Minister and neuroscientist respectively, which was helpful in establishing the interdisciplinary credibility I was seeking.

It took some persuading, but SUNY agreed to use as cover art a painting from my good friend Josh Adam, who has become one of the great landscape painters of our generation. Generous back-cover endorsements were provided by Jeremy Taylor and Tore Nielsen, a Unitarian-Universalist Minister and neuroscientist respectively, which was helpful in establishing the interdisciplinary credibility I was seeking.

“Dreamy” is one of the adjectives most often used to describe the cinematic art of David Lynch, and justifiably so. Below are two journal articles I have written about his works in which I explore and celebrate his aesthetic dreaminess, especially in the films Mulholland Drive, Lost Highway, Blue Velvet, and the television series Twin Peaks and Twin Peaks: The Return.

“Dreamy” is one of the adjectives most often used to describe the cinematic art of David Lynch, and justifiably so. Below are two journal articles I have written about his works in which I explore and celebrate his aesthetic dreaminess, especially in the films Mulholland Drive, Lost Highway, Blue Velvet, and the television series Twin Peaks and Twin Peaks: The Return. The remaining exterior work at the Dream Library is down to roofing and painting. The focus will turn soon to the interior finish work of electrical, plumbing, and bookcase installation. Designing and installing a spiral staircase from the second floor to the third floor tower will be a special aesthetic and practical task. When the weather becomes less soggy, careful attention will go to perimeter landscaping, with the top priority of long-term fire safety–a vital concern for a building full of paper, built of wood, and surrounded by a forest.

The remaining exterior work at the Dream Library is down to roofing and painting. The focus will turn soon to the interior finish work of electrical, plumbing, and bookcase installation. Designing and installing a spiral staircase from the second floor to the third floor tower will be a special aesthetic and practical task. When the weather becomes less soggy, careful attention will go to perimeter landscaping, with the top priority of long-term fire safety–a vital concern for a building full of paper, built of wood, and surrounded by a forest. Houses and homes are among the most frequent elements appearing in dreams, with a wide range of literal and symbolic meanings.

Houses and homes are among the most frequent elements appearing in dreams, with a wide range of literal and symbolic meanings. Construction is going well so far on the Dream Library, a stand-alone structure on a rural, forested property near Portland, Oregon. As many friends and colleagues know, the project has taken a long time to reach this stage, but at last it’s beginning to take actual shape. The building will provide a long-term archive for dream-related materials such as journals, books, and art. The journal & book collections of Jeremy Taylor and Patricia Garfield will form the core of the library, along with other donated materials and my own collections.

Construction is going well so far on the Dream Library, a stand-alone structure on a rural, forested property near Portland, Oregon. As many friends and colleagues know, the project has taken a long time to reach this stage, but at last it’s beginning to take actual shape. The building will provide a long-term archive for dream-related materials such as journals, books, and art. The journal & book collections of Jeremy Taylor and Patricia Garfield will form the core of the library, along with other donated materials and my own collections.

The bizarre contents of dreaming can easily seem like the products of mental deficiency. “Children of an idle brain” is what Mercutio calls them in Romeo & Juliet (I.iv.102). Many scientists today essentially agree with Mercutio that the weird absurdities of dreams are evidence of diminished cognitive functioning during sleep.

The bizarre contents of dreaming can easily seem like the products of mental deficiency. “Children of an idle brain” is what Mercutio calls them in Romeo & Juliet (I.iv.102). Many scientists today essentially agree with Mercutio that the weird absurdities of dreams are evidence of diminished cognitive functioning during sleep.