The 23rd of April is the traditional day for celebrating English playwright William Shakespeare’s birth in 1564. April 23 also happens to be the date on which he died in 1616, at the age of 52. A special reason to reflect on his legacy this year is the 400th anniversary of the publication in 1623 of the “First Folio,” the original collection of his works.

The 23rd of April is the traditional day for celebrating English playwright William Shakespeare’s birth in 1564. April 23 also happens to be the date on which he died in 1616, at the age of 52. A special reason to reflect on his legacy this year is the 400th anniversary of the publication in 1623 of the “First Folio,” the original collection of his works.

One way to appreciate the psychological value of Shakespeare’s plays is to look at his characters as case studies of mental and emotional typology. In this view, the character of King Lear gives us a vivid and psychologically accurate portrayal of an aging man struggling with mortality and loss of power. Many other examples like this emerge in the plays. Othello can be seen as embodying the violent irrationality of jealousy. Lady Macbeth shows the deranging effects of intense guilt. Falstaff exemplifies a life driven by animal appetites. Ophelia illustrates the suicidal despair of a dissolving self. When Freud first introduced his idea of the Oedipal complex and the dynamics of desire in parent-child relations in The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), he immediately connected it to the Bard: “Another of the great creations of tragic poetry, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, has its roots in the same soil as Oedipus Rex.

As useful as these analyses may be as a form of psychological shorthand, we need to be careful not to let such a reductive approach diminish either the characters or the plays, which are always larger than just one perspective can encompass. Trying to think in broader terms about Shakespeare’s works as a whole and their ongoing relevance to psychology, the following three general themes seem to me the clearest and most significant.

Respect for psychological diversity: Over the course of 38 plays, Shakespeare created hundreds of characters with an astonishing variety of personalities, thoughts, feelings, motivations, and behaviors. Even more impressively, he gave each of them a distinctive voice and fully-realized presence within the world of their play, enabling them to articulate their individual human experiences (most explicitly in their soliloquy speeches, alone on stage with the audience). In a striking expression of this humanistic, diversity-embracing spirit, Shakespeare never demonizes his villains, nor does he deify his heroes. The bad characters (Iago, Caliban, Richard III) are definitely bad, but they are also portrayed with genuinely sympathetic qualities. The good characters (Henry V, Prospero, Rosalind) are truly good, but we see their flaws and vulnerabilities, too.

The power of the imagination: Many of Shakespeare’s plays build up dense networks of metaphorical interaction between sleep, dreaming, illusion, madness, children’s play, love, revelation, and the practice of theater itself. Some of the most psychologically acute speeches in the plays revolve around this theme of the mind’s image-generating power in its many manifestations. Although wild and dangerous, Shakespeare portrays the human imagination as a creative source of new critical awareness of ourselves, society, and the world around us. In this way, his plays provide a kind of psychological map of the symbolic resonances between different realms of imaginal experience.

Transformative effects of art: Shakespeare not only created plays with a wide range of characters, he also created plays for a wide range of audiences. His stories addressed everyone in his society, from the elite royals to the lowly groundlings and everyone in between. The plays were meant to be entertaining, of course, but it seems that Shakespeare wanted to have a deeper impact on his audience by stimulating, within the imaginal space of live theater, a flow of provocative insights about individual and collective life. These dramatically-generated insights can have transformative effects because they unsettle our assumptions and open our minds to surprise, wonder, and growth. Even for the audiences of Shakespeare’s time, his plays were hard to understand. He twisted traditional tales, subverted conventional genres, used an endless stream of bizarre words, mixed ethereal poetry with bawdy puns, and devised elaborately convoluted plots. He intentionally kept his audiences off-balance and uncertain, not to confuse them but to open their eyes to fresh possibilities of human experience, to new dimensions of perception, feeling, and empathic connection. At the risk of anachronism, I’d say we should appreciate mind-expanding complexity as a feature of Shakespeare’s art, not a bug.

Happy birthday, Will!

(This post was first published on the website of Psychology Today, April 18, 2023.)

Elsewhere is a new dream journaling app, created by an international team of people who are avid dream journal-keepers themselves. Available for both iOS and Android systems, it’s a safe, private space to record your dreams, track them over time, and learn about their unfolding patterns of meaning. Elsewhere offers a variety of analytic tools and fun interactive features, with even better features soon to come.

Elsewhere is a new dream journaling app, created by an international team of people who are avid dream journal-keepers themselves. Available for both iOS and Android systems, it’s a safe, private space to record your dreams, track them over time, and learn about their unfolding patterns of meaning. Elsewhere offers a variety of analytic tools and fun interactive features, with even better features soon to come.

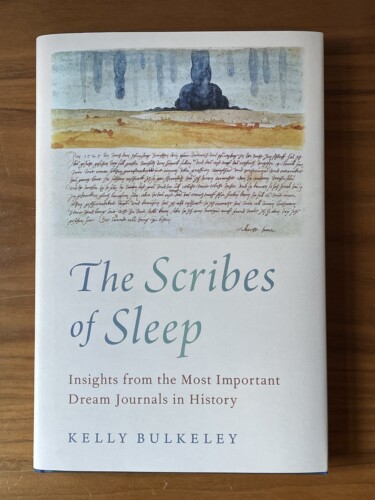

My latest book, The Scribes of Sleep, has just been published by Oxford University Press. It’s a work dedicated to people who keep dream journals, as a new resource for learning more about the fascinating and largely unknown history of dream journal practices. The book is also intended as an argument in favor of dream journals as a valuable source of empirical data for scientific research into the nature and functions of dreaming.

My latest book, The Scribes of Sleep, has just been published by Oxford University Press. It’s a work dedicated to people who keep dream journals, as a new resource for learning more about the fascinating and largely unknown history of dream journal practices. The book is also intended as an argument in favor of dream journals as a valuable source of empirical data for scientific research into the nature and functions of dreaming.

Most people who keep a dream journal are initially motivated by simple curiosity and the hope they will gain insights into their waking lives. But as they continue with the journaling and track the emerging patterns of their dreams over time, they often find the process becomes something more than that, something that develops a life of its own and opens into a new relationship with the unconscious realms of their minds.

Most people who keep a dream journal are initially motivated by simple curiosity and the hope they will gain insights into their waking lives. But as they continue with the journaling and track the emerging patterns of their dreams over time, they often find the process becomes something more than that, something that develops a life of its own and opens into a new relationship with the unconscious realms of their minds. The 23rd of April is the traditional day for celebrating English playwright William Shakespeare’s birth in 1564. April 23 also happens to be the date on which he died in 1616, at the age of 52. A special reason to reflect on his legacy this year is the 400th anniversary of the publication in 1623 of the “First Folio,” the original collection of his works.

The 23rd of April is the traditional day for celebrating English playwright William Shakespeare’s birth in 1564. April 23 also happens to be the date on which he died in 1616, at the age of 52. A special reason to reflect on his legacy this year is the 400th anniversary of the publication in 1623 of the “First Folio,” the original collection of his works. Many dreams contain recurrent elements that have appeared in previous dreams. These elements include characters you have encountered before, in settings where you have been before, doing things you have done before. The long-term consistency of your dreaming offers a unique window into the nature of your personality and the foundational realities of your waking life.

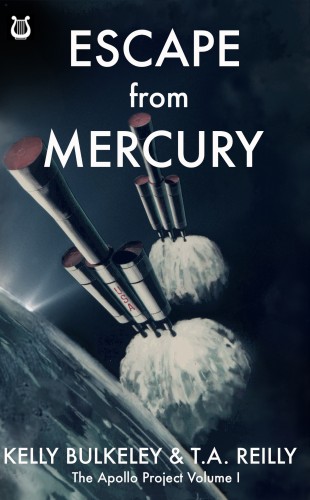

Many dreams contain recurrent elements that have appeared in previous dreams. These elements include characters you have encountered before, in settings where you have been before, doing things you have done before. The long-term consistency of your dreaming offers a unique window into the nature of your personality and the foundational realities of your waking life. Escape from Mercury

Escape from Mercury