Between January 8, 2015 and October 4, 2017, I remembered and recorded a dream every night for 1,001 consecutive nights. Now I’m studying the dreams and trying to find insights that can help in exploring the dream series of other people. I don’t expect anyone to accept my personal dreams as conclusive evidence for any general theory of human dreaming. Instead, I offer them as way of being transparent about the experiential grounding of my research pursuits. This is one of the ways I get ideas for new projects.

Between January 8, 2015 and October 4, 2017, I remembered and recorded a dream every night for 1,001 consecutive nights. Now I’m studying the dreams and trying to find insights that can help in exploring the dream series of other people. I don’t expect anyone to accept my personal dreams as conclusive evidence for any general theory of human dreaming. Instead, I offer them as way of being transparent about the experiential grounding of my research pursuits. This is one of the ways I get ideas for new projects.

All of the dreams are available online for further study in the SDDb, in the “Sample Data” section.

From a scientific perspective, the value of an introspective project such as this is to generate working hypotheses for future studies. Trying to study another person’s long diary of dreams can be very challenging, especially at the outset when the researcher is facing a huge mass of texts with multiple dimensions of meaning. I appreciate anything that can provide some initial orientation and help to steer the direction of the analysis. By studying my own dreams, which I know from both a first- and third-person perspective, I can quickly and easily identify some patterns of meaning that seem worth further exploration. Maybe they will apply to someone else’s dream series, maybe they won’t; either way, it helps the analytic process get going.

Remembering and Recording the Dreams

The method I use for keeping my dream journal is fairly typical. I keep a pad of paper and a pen by my bedside, and when I wake up in the morning I immediately write down whatever dreams I can remember, before getting out of bed or turning on the light. Then later in the morning I type the dream into a digital file, along with associations, memories, and thoughts about what the dream might mean.

During the three years of recording this series of 1,001 dreams, I did my best to wake up slowly each morning, so the images and feelings from the preceding dreams could coalesce in my memory. I don’t believe I dreamed more during this time than I did in previous periods of my life; rather, I devoted more energy to remembering the wispier, more evanescent kinds of dreams that, in previous years, had not crossed the threshold into waking memory. I made a more determined effort to protect the space around the transition from sleeping to waking, even during circumstances when that was difficult to do (e.g., on international plane flights, during family holidays). Often it took a few moments of quietly lying in bed with my eyes closed before the vague feeling “I know I was just dreaming,” could eventually take form into a specific memory of what I was just dreaming about. Often there were “aha!” moments when suddenly a whole long dream came back to me, which I surely would have forgotten if I had immediately leapt out of bed upon awakening.

I also put more conscious intention into the other end of the transition, from waking into sleeping, as I carefully set up my journal and pen each night before turning out the light. I did not set specific dream incubation questions during this time, but simply tried to signal to myself that I was ready and willing to record whatever dreams might come during that night’s sleep.

These were not extreme or burdensome behaviors; they required consistency of purpose, but no heroic feats of will. I never set any long-term goals or numerical targets. Instead, I just focused on each new night and each new dream, figuring the time would come when I could survey the series from a broader perspective.

About a month ago I finally did the math, and realized that October 4th would mark 1,001 nights of dream recall in a row, an enchanting milestone. This seemed like a large enough collection of dreams to pause, look back, and see what I could learn.

Patterns of Word Usage

The reports comprise a total of 93,050 words, with an average length per dream report of 93 words, and a median length of 73 words. The shortest dream in the series has 9 words, and the longest has 728 words. The average length of these dreams is not unusual, compared to other people whose dreams have been analyzed in this way. Some people have much longer dreams than I do, and some people have much shorter dreams. This series of 1,001 dreams, then, includes mostly dreams of middling length.

To highlight the patterns and themes in a series like this, I start by comparing it to what I call the “SDDb baselines,” two large collections of male (N=2,135) and female (N=3,110) dreams that have been systematically gathered and analyzed using a template of 8 classes and 40 categories of word usage. I use the baselines a measuring stick for identifying possible continuities and discontinuities between the dreams and the individual’s waking life.

The results of this comparative analysis are presented in an accompanying spreadsheet, “1001 Nights Data.” Some of the discussion below draws on an earlier analysis I wrote about an overlapping set of my dreams.

In relation to the SDDb baselines (an average of 100 words per report for the females and 105 for the males), my dreams are a little shorter than average (93 words per report). The results for each of the 8 classes of word usage are summarized below. Compared to the male and female baselines, my 1,001 dreams have:

- Perception: More references to vision and colors.

- Emotion: Many more references to wonder/confusion, and more to happiness.

- Characters: Fewer references to family characters (although the word “wife” is mentioned very frequently), more references to animals (especially cats), and slightly more references to females than males.

- Social Interactions: Slightly more references to sexuality.

- Movement: Fewer references to death.

- Cognition: More references to thought, fewer to speech.

- Culture: Fewer references to school, food/drink, religion, somewhat more to sports (especially baseball and basketball).

- Elements: More references to water, somewhat more to earth.

These findings provide the basis for a “blind analysis,” which means making predictions about continuities between these patterns of word usage in dreaming and the individual’s waking life activities, beliefs, and concerns. If I pretend I knew nothing about the dreamer of these 1,001 dreams, and I only had these word usage frequencies to consider, I would infer this individual:

- Is visually oriented

- Often experiences wonder/confusion

- Is relatively happy

- Is married

- Cares about cats

- Has fairly equal relations with men and women

- Is sexually active

- Is not concerned about death

- Is not highly verbal

- Is not highly involved with schools

- Is not highly concerned about food/drink

- Is not highly concerned about religion

- Has lots of interactions with water and earth

Most of these inferences—I’d say 11 of 13—are unmistakably accurate in identifying a continuity between a pattern of dream content and an aspect of my waking life concerns. The two I would question are numbers 10 and 12. Regarding the low frequency of dream references to school, I do in fact engage in a great deal of teaching and educational work, but it’s almost entirely online, and I rarely set foot inside a traditional school any more. Also, I no longer have school-age children living at home. So it seems my dreams are continuous with my physical behaviors relating to schools, but not with my computer-mediated educational activities.

Most of these inferences—I’d say 11 of 13—are unmistakably accurate in identifying a continuity between a pattern of dream content and an aspect of my waking life concerns. The two I would question are numbers 10 and 12. Regarding the low frequency of dream references to school, I do in fact engage in a great deal of teaching and educational work, but it’s almost entirely online, and I rarely set foot inside a traditional school any more. Also, I no longer have school-age children living at home. So it seems my dreams are continuous with my physical behaviors relating to schools, but not with my computer-mediated educational activities.

Regarding the low frequency of religion references, I most certainly do have great interest in religion, going back to my masters and doctoral studies at the Divinity Schools of Harvard and University of Chicago. So the inference seems very wrong at this level. And yet, at another level it seems more accurate. I was not raised in a religious household, I do not personally identify with any official religious tradition, and I rarely attend religious worship services. Compared to other people I’ve studied with very high frequencies of references to religion in their dreams, I am a much less personally pious person. Perhaps what this suggests is that the dreams are accurately reflecting the fact that religion may be an important intellectual category for me, but it is not a personal concern. My spiritual pursuits are more likely to be expressed in dreams with references to other word categories like water, art, sexuality, animals, and flying.

Shorter versus Longer Dreams

Earlier this year I looked at different set of my dreams to get some idea about possible differences between shorter and longer dreams. This question rose in relevance when I realized, as noted earlier, that my increased recall seemed to depend in part on the recollection of relatively shorter dreams that in the past I did not fully remember or write down.

There were two main findings of that earlier study. First, most of the patterns in content appeared in dreams of all lengths, from the shortest (less than 50 words per report) to the longest (more than 150 words per report). Here’s a summary of what I found:

“The results of this analysis suggest that shorter dreams are not dramatically different from longer dreams in terms of the relative proportions of their word usage. The raw percentages of word usage do rise from shorter to longer dreams, of course, but the relative proportions generally do not.”

Second, the longer dreams did have proportionally more references to a few word categories, chiefly Fear, Speech, Walking/Running, and Transportation. Another quote:

“These are the word categories that seem to be over-represented in longer dreams. They are significant contributors to what makes long dreams so long.”

Returning to the present collection of 1,001 dreams, I divided the series at the median point into two groups: the shorter dreams (72 words or less, 500 reports total) and the longer dreams (73 words or more, 501 reports total). I used the same SDDb word searching template with each of the two groups as I used with the full series, and then I compared their frequencies of word usage. The biggest variations between the shorter and longer dreams appeared in the following categories:

- Touch

- Fear

- Anger

- Physical aggression

- Walking/Running

- Speech

- Transportation

- Water

This list adds a few other categories that may be characteristic of longer dreams. Each of these categories has a dynamic quality. Touch is a physical interaction. Fear and anger are strong and unpredictable emotions, usually prompted by something in the external environment. Physical aggression combines the previous categories (touch, fear, anger) and possibly intensifies them. Walking/Running and Transportation both involve physical movement from one place to another. Speech implies a context of interpersonal communication, people talking with each other. Water, the “universal solvent,” is ever-shifting in its states (gas, liquid, solid) and its movement through human life.

When these elements appear in my dreams they seem to have the effect of expanding the range of experience, stimulating more interactions, and lengthening the narrative.

Conclusion

I don’t know if any of this applies to anyone else’s dreams. I do, though, believe that several of the insights gained here can provide working hypotheses for studying other series of dreams. I will be keeping these ideas in mind as I explore new dream series:

- The recall and recording methods of the dreamer influence the types of dreams included in the series.

- Personal relationships are an area of especially strong continuity between waking and dreaming life.

- The use of religion-related words in dreams may be discontinuous with spiritual interests in waking life.

- Shorter dreams have mostly the same general proportions and patterns of content as found in longer dreams.

- Longer dreams tend to include more dynamic elements.

####

Notes:

The accompanying spreadsheet can be found here:

https://www.academia.edu/35024762/1001_Nights_Data.xlsx

More description of the SDDb baselines can be found in Big Dreams: The Science of Dreaming and the Origins of Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

The earlier study of short versus long dreams can be found here:

Short vs. Long Dreams: Are There Any Differences in Content?

There is a surprisingly easy way to stimulate an intense phase of dreaming, if you’re willing to take advantage of the “rebound effect” of sleep deprivation. The rebound effect is a term for when a person sleeps longer than usual after a period of sleeping shorter than usual. The magnitude of the rebound depends on 1) the severity of the sleep deprivation and 2) the freedom to sleep without awakening after the deprivation.

There is a surprisingly easy way to stimulate an intense phase of dreaming, if you’re willing to take advantage of the “rebound effect” of sleep deprivation. The rebound effect is a term for when a person sleeps longer than usual after a period of sleeping shorter than usual. The magnitude of the rebound depends on 1) the severity of the sleep deprivation and 2) the freedom to sleep without awakening after the deprivation.

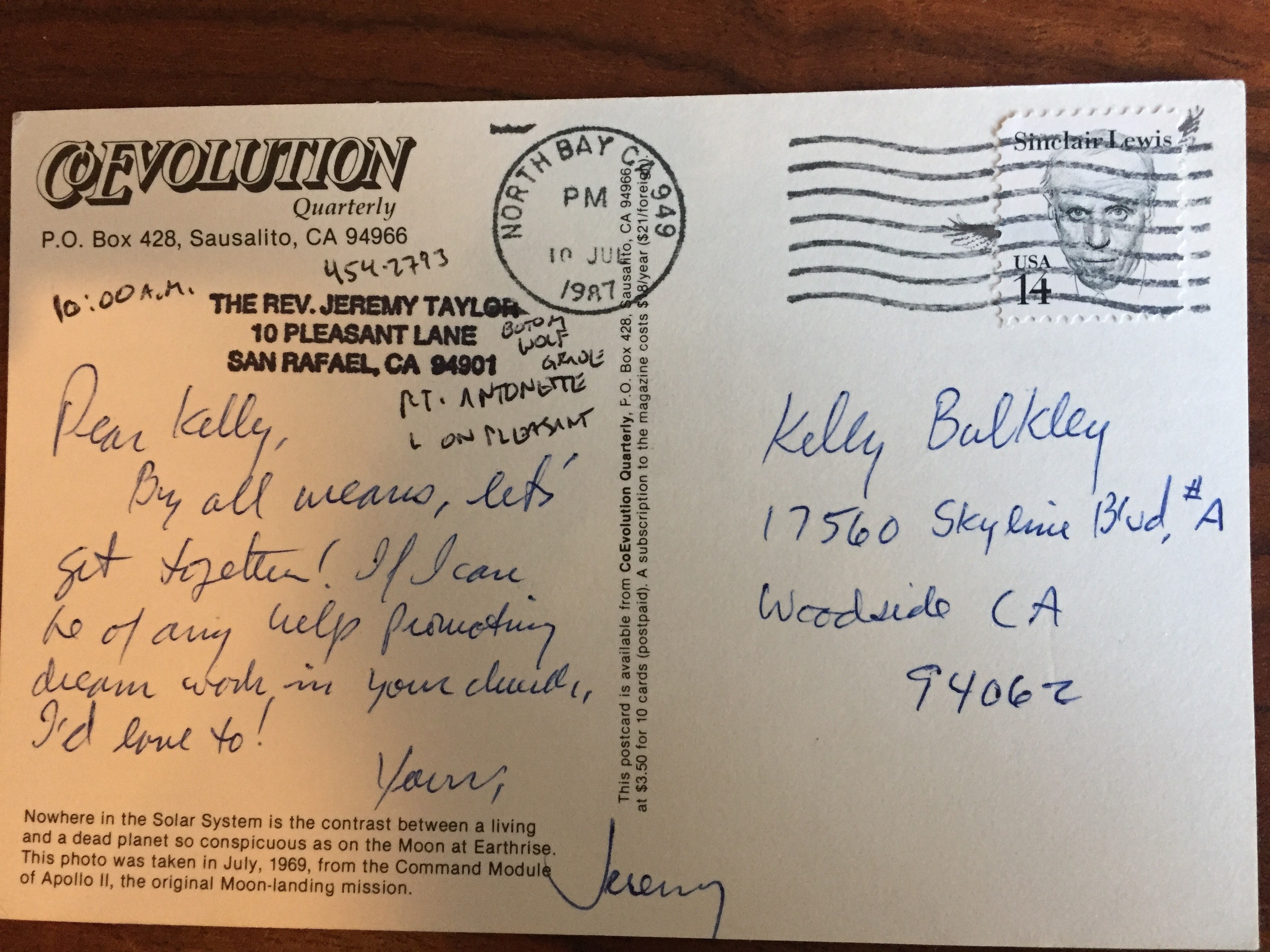

The Rev. Jeremy Taylor was one of the most prolific dream speakers and teachers of modern times. He traveled to every corner of the U.S., and to many countries around the world, reaching out to people and promoting greater awareness of dreaming. He combined his background as a Unitarian-Universalist minister with a deep familiarity with Jungian archetypal psychology to not only help people better understand their dreams, but to get them excited and energized about the amazing adventure of psychological growth and spiritual discovery that opens up once they start paying more attention to general human experience of dreaming.

The Rev. Jeremy Taylor was one of the most prolific dream speakers and teachers of modern times. He traveled to every corner of the U.S., and to many countries around the world, reaching out to people and promoting greater awareness of dreaming. He combined his background as a Unitarian-Universalist minister with a deep familiarity with Jungian archetypal psychology to not only help people better understand their dreams, but to get them excited and energized about the amazing adventure of psychological growth and spiritual discovery that opens up once they start paying more attention to general human experience of dreaming.

The most important findings of scientific dream research can be summarized in nine key points. Many important questions about dreaming remain unanswered, but these nine findings have solid empirical evidence to support them.

The most important findings of scientific dream research can be summarized in nine key points. Many important questions about dreaming remain unanswered, but these nine findings have solid empirical evidence to support them.

Books about dreams are excellent holiday presents—easy to give and enjoyable to receive. They are widely available for purchase, fairly inexpensive, simple to wrap and ship, and sure to bring surprise and delight (and perhaps life-changing illumination) to their recipients. If you have a long list of people for whom you’re trying to buy gifts in the next few weeks, consider getting them one or more of these excellent new books, which have come out in 2017 or 2016.

Books about dreams are excellent holiday presents—easy to give and enjoyable to receive. They are widely available for purchase, fairly inexpensive, simple to wrap and ship, and sure to bring surprise and delight (and perhaps life-changing illumination) to their recipients. If you have a long list of people for whom you’re trying to buy gifts in the next few weeks, consider getting them one or more of these excellent new books, which have come out in 2017 or 2016.

Between January 8, 2015 and October 4, 2017, I remembered and recorded a dream every night for 1,001 consecutive nights. Now I’m studying the dreams and trying to find insights that can help in exploring the dream series of other people. I don’t expect anyone to accept my personal dreams as conclusive evidence for any general theory of human dreaming. Instead, I offer them as way of being transparent about the experiential grounding of my research pursuits. This is one of the ways I get ideas for new projects.

Between January 8, 2015 and October 4, 2017, I remembered and recorded a dream every night for 1,001 consecutive nights. Now I’m studying the dreams and trying to find insights that can help in exploring the dream series of other people. I don’t expect anyone to accept my personal dreams as conclusive evidence for any general theory of human dreaming. Instead, I offer them as way of being transparent about the experiential grounding of my research pursuits. This is one of the ways I get ideas for new projects. Most of these inferences—I’d say 11 of 13—are unmistakably accurate in identifying a continuity between a pattern of dream content and an aspect of my waking life concerns. The two I would question are numbers 10 and 12. Regarding the low frequency of dream references to school, I do in fact engage in a great deal of teaching and educational work, but it’s almost entirely online, and I rarely set foot inside a traditional school any more. Also, I no longer have school-age children living at home. So it seems my dreams are continuous with my physical behaviors relating to schools, but not with my computer-mediated educational activities.

Most of these inferences—I’d say 11 of 13—are unmistakably accurate in identifying a continuity between a pattern of dream content and an aspect of my waking life concerns. The two I would question are numbers 10 and 12. Regarding the low frequency of dream references to school, I do in fact engage in a great deal of teaching and educational work, but it’s almost entirely online, and I rarely set foot inside a traditional school any more. Also, I no longer have school-age children living at home. So it seems my dreams are continuous with my physical behaviors relating to schools, but not with my computer-mediated educational activities.