A brilliant exploration of the dark psychological depths of sexual desire appears in an unlikely place—a country musical from the 1940’s.

A brilliant exploration of the dark psychological depths of sexual desire appears in an unlikely place—a country musical from the 1940’s.

Oklahoma! was the first collaboration of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, the duo who went on to write many of Broadway’s most famous mid-century musicals. A new production of Oklahoma! at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival promises to stimulate new interest in this classic theatrical work through innovative casting, staging, and choreography from director Bill Rauch and choreographer Ann Yee.

Oklahoma! offers a surprisingly complex portrait of dreaming, desire, and the unconscious mind, and I plan to write a more detailed appraisal once the OSF production opens in April. To set the stage, as it were, I wanted to start with an overview of the traditional production, which opened in 1943 and has since been performed in thousands of other venues in the US and around the world. An Academy Award-winning movie adaptation appeared in 1955.

Set in the Oklahoma territory in 1906, just before official statehood, the story revolves around two love triangles. In one, a cowboy (Curly) and a farmhand (Jud) vie for the affections of a farmer’s daughter (Laurey). In the other, cowboy Will Parker and a Persian traveling salesman named Ali Hakim are both involved with Ado Annie, one of Laurey’s friends.

The play both opens and closes with the joyfully optimistic song “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’,” and the action unfolds in the space created between those two happy moments of dawning light.

In the very center of the play, at the end of the Act I, there is a dark and very elaborate dream sequence, “The Dream Ballet,” intended to express Laurey’s conflicted feelings about Curley and Jud. Other plays and musicals before Oklahoma! had included scenes of dancing framed as dreams, but no one had ever pushed the dream theme into such bold psychological territory, with so much sophistication and artistry in the choreography. Much of the credit goes to Agnes de Mille, the original choreographer, who helped Rogers and Hammerstein craft what became one of the most famous scenes in the play.

In the scene just before the ballet, Jud is alone and brooding about his sexual frustration. The pornographic “postcards” in his room excite his fantasies (“And a dream starts a-dancin’ in my head”), but ultimately leave him feeling empty, deceived, and even angrier than before. He finally declares, “I ain’t gonna dream ‘bout her arms no more!” and sets off to claim Laurey for his own.

Laurey, meanwhile, sits down in the shade of a tree in her yard and drinks a special sleeping potion (“the Elixir of Egypt”) she purchased from Ali Hakim, hoping it will “make up my mind fer me” and help her “to see things clear.” She slowly nods off, while a group of neighboring girls sing a lullaby about flying from her dreams into the arms of the man she truly loves. The girls disappear, Laurey falls into a deep sleep, and the dream begins.

Each of the characters in the main love triangle has a kind of dream-world counterpart or avatar, a professional dancer who performs their roles during the 17-minute sequence. It begins well enough, with Laurey dancing “ecstatically” with Curly. After many vigorous upward thrusts and arousing leaps through the air, they find themselves at a wedding, walking down the aisle, about to take their vows. But at the last moment it is Jud, not Curly, who appears in front of her. Laurey is terrified as Jud and the risqué women from his postcards take over the dream. Curly has a gun and tries to shoot Jud, but the gun has no effect. Jud attacks Curly and starts choking him to death. Laurey begs Jud to stop, and promises to go with him if he will spare Curly’s life. Jud agrees, and takes Laurey with him, as she bids a “heartbroken” farewell to Curly.

At this moment, Jud walks up to the tree in her yard. “Wake up, Laurey,” he says, “It’s time to start fer the party.” Just then Curly walks up to the house, too, hoping she will choose him instead. Laurey, now fully awake, is seized with panic:

“Remembering the disaster of her recent dream, she avoids its reality by taking Jud’s arm and going with him, looking wistfully back at Curly with the same sad eyes that her ballet counterpart had on her exit. Curly stands alone, puzzled, dejected and defeated, as the curtain falls.”

This marks the end of Act I.

The provocative content and staging of the Dream Ballet was originally envisioned by Hammerstein to be “bizarre, imaginative and amusing, and never heavy.” (Carter 129) De Mille, however, wanted to shift the tone; she suggested bringing Jud’s postcard girls into the action, and making the whole thing darker and gloomier. Virtually all musicals try to send their audiences into intermission on a happy, buoyant note; the Dream Ballet of Oklahoma! has the diametrically opposite effect, which de Mille felt would be entirely appropriate for Laurey’s character and situation at this point in the story.

In a later interview, de Mille said she pushed Hammerstein to make the dream sequence more emotionally realistic, more like the kinds of anxiety dreams that girls and young women actually experience: “Girls don’t dream about the circus. They dream about horrors. And they dream dirty dreams.” (Carter 123)

Thus, the core moment in one of America’s most beloved works of musical theater is a violently realistic sexual nightmare.

The Dream Ballet is an amazing work of art. It is also a remarkably insightful portrait of the dreaming mind. For those who study dreams, Oklahoma! raises a number of intriguing questions that can shed new light on the play, its cultural impact, and the dreaming imagination. I will wait to see the OSF production in late April before saying more, but these are some of the anticipatory questions and ideas dancing through my mind:

Was Agnes de Mille right, as a matter of empirical fact, that girls have a tendency to dream about “horrors” and “dirty” topics? What might modern research on the dream patterns of young women reveal about the unconscious dynamics of Laurey’s dilemma?

Has Laurey unknowingly performed a ritual of dream incubation? She drinks the “Elixir of Egypt,” sleeps in a special place, focuses her mind on a particular question as she drifts off, and then has a dream relating to her question. That’s pretty much the definition of a dream incubation ritual (as per Kimberley Patton.)

Is Laurey’s dream a threat simulation, along the lines of what Antti Revonsuo has proposed? Revonsuo focused on recurrent chasing nightmares as an instance of dreams that simulate a possible threat and rehearse our response to it, so we’re better prepared in waking life if that threat should actually arise. Laurey has a dream of Jud threatening to kill Curly, which is indeed a realistic appraisal of the dangers in her waking life.

Is her dream a sexual wish-fulfillment, as Sigmund Freud would say? In 1940’s New York City, it’s a fair guess the Oklahoma! creative team knew about psychoanalysis and its theories about unconscious sexual desires. Laurey certainly has a more intense and erotic interaction with Curly in dreaming than she ever does in waking. The dream’s sexual charge only grows with the appearance of Jud’s postcard girls, who stir up even more libidinal energy, with less romance and more raw carnal desire. And poor Curly with his limp gun…

Is Jud a shadow symbol for Laurey and the whole Oklahoma community, as Carl Jung might suggest? From the very beginning of the play Jud is portrayed as dark, crude, rough, hairy, animal-like, stupid, and inarticulate. He lives alone in a “smokehouse,” seething with unfulfilled instinctual urges. He could be seen as a radical Other, in the symbolic lineage of Lucifer, Caliban, Gollum, and Darth Vader, the embodiment of all the darkness that is not allowed into the light of conscious awareness, and thus banished to the depths of the unconscious.

Does Laurey misinterpret her dream? How exactly is her action upon awakening (choosing Jud over Curly) justified by what she has dreamed? In both fiction and real life, people who instantly interpret their dreams usually get it wrong. The quick response often overlooks deeper, more important meanings that the conscious mind may be all to ready to move past. (I call this “the Odyssean fallacy.”)

Does Jud misinterpret his dream? Same question—why does Jud think the action he takes (aggressively demanding Laurey’s affection) is justified by his arousing yet frustrating dreams of the postcard girls? What might he be overlooking?

Finally, how will the OSF creative team reimagine this classic work for a new century and a new America?

I can’t wait to see!

Reference: Tim Carter, Oklahoma!: The Making of an American Musical, Yale University Press, 2007.

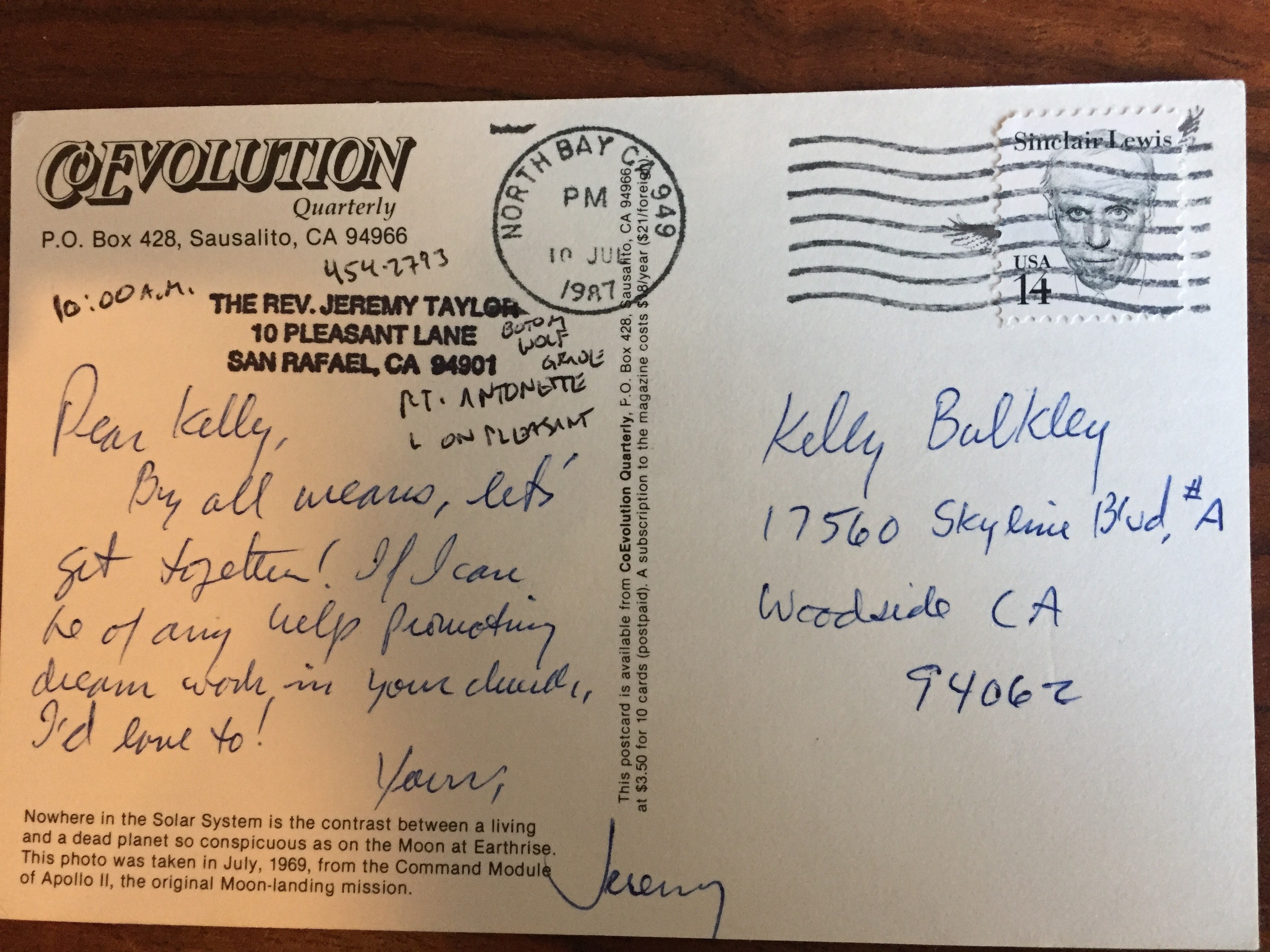

Following the death a few weeks ago of Jeremy Taylor and his wife Kathy, I spoke with their daughter Tristy, and we agreed that I would take responsibility for moving, storing, and preserving his professional books and papers. Tristy understands that her father had a major influence on the contemporary study of dreams, and his works will have an enduring historical significance for the field. I told her that my wife and I have recently begun working with an architect to design a study and library devoted to dream research on property we own near Portland, so I can offer a place where his collection will be available to other dream investigators in the future.

Following the death a few weeks ago of Jeremy Taylor and his wife Kathy, I spoke with their daughter Tristy, and we agreed that I would take responsibility for moving, storing, and preserving his professional books and papers. Tristy understands that her father had a major influence on the contemporary study of dreams, and his works will have an enduring historical significance for the field. I told her that my wife and I have recently begun working with an architect to design a study and library devoted to dream research on property we own near Portland, so I can offer a place where his collection will be available to other dream investigators in the future.

There is a surprisingly easy way to stimulate an intense phase of dreaming, if you’re willing to take advantage of the “rebound effect” of sleep deprivation. The rebound effect is a term for when a person sleeps longer than usual after a period of sleeping shorter than usual. The magnitude of the rebound depends on 1) the severity of the sleep deprivation and 2) the freedom to sleep without awakening after the deprivation.

There is a surprisingly easy way to stimulate an intense phase of dreaming, if you’re willing to take advantage of the “rebound effect” of sleep deprivation. The rebound effect is a term for when a person sleeps longer than usual after a period of sleeping shorter than usual. The magnitude of the rebound depends on 1) the severity of the sleep deprivation and 2) the freedom to sleep without awakening after the deprivation. The Rev. Jeremy Taylor was one of the most prolific dream speakers and teachers of modern times. He traveled to every corner of the U.S., and to many countries around the world, reaching out to people and promoting greater awareness of dreaming. He combined his background as a Unitarian-Universalist minister with a deep familiarity with Jungian archetypal psychology to not only help people better understand their dreams, but to get them excited and energized about the amazing adventure of psychological growth and spiritual discovery that opens up once they start paying more attention to general human experience of dreaming.

The Rev. Jeremy Taylor was one of the most prolific dream speakers and teachers of modern times. He traveled to every corner of the U.S., and to many countries around the world, reaching out to people and promoting greater awareness of dreaming. He combined his background as a Unitarian-Universalist minister with a deep familiarity with Jungian archetypal psychology to not only help people better understand their dreams, but to get them excited and energized about the amazing adventure of psychological growth and spiritual discovery that opens up once they start paying more attention to general human experience of dreaming.

The most important findings of scientific dream research can be summarized in nine key points. Many important questions about dreaming remain unanswered, but these nine findings have solid empirical evidence to support them.

The most important findings of scientific dream research can be summarized in nine key points. Many important questions about dreaming remain unanswered, but these nine findings have solid empirical evidence to support them.