Werner Herzog’s documentary “Cave of Forgotten Dreams” has just been released in the US, and it’s worth seeing for anyone interested in paleolithic cave art and the origins of human consciousness.

Werner Herzog’s documentary “Cave of Forgotten Dreams” has just been released in the US, and it’s worth seeing for anyone interested in paleolithic cave art and the origins of human consciousness.

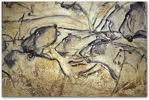

The Chauvet caves of Southern France contain paintings dating back more than 30,000 years. Herzog was granted a brief amount of time to take a small film crew into most, but not all, of the cave system. The project undoubtedly appealed to Herzog’s gonzo filmmaking impulses, but he also found a proto-cinematic quality to the paintings that seemed to evoke for him a feeling of kinship between modern director and paleolithic cave-painter.

He interviewed several scientists and cave mavens, not all of whom add much to our understanding of the cave paintings. But there’s a cool French archeologist with pony tail and scarf who says he began dreaming of lions after spending five days of intensive research in the portion of the cave filled with lion images. He’s my new hero!

As the film goes on and viewers become better oriented within the caves and more acclimated to their 3D glasses, Herzog presents several long, contemplative scenes that bring to life the implicit energy and vitality in the overlapping multitude of animal figures. I appreciate Herzog’s willingness to acknowledge the deep psychological impact the paintings have, and to consider the implications that the paintings were designed for that very purpose–to elicit feelings of wonder and awe, to expand the viewer’s imagination, to hint at realities beyond the visible and below the surface.

I loved Cave of Forgotten Dreams! Herzog’s excellent use of the immersive 3D experience not only gives viewers a near-realistic view of the paintings, it creates an almost lucid imagining of the painter’s reality some 30,000 years ago.

I too was struck by the juggler-turned-archaeologist who dreamed of lions nonstop after visiting the caves. But what really held my attention was how the film crew worked together in silence, using handheld lights and cameras, to cast shadows on the undulating walls and thus create movement from utter stillness. Their presence in the frame was not a distraction, but rather served to heighten the sense of traveling back through millennia into a dream time.